Massaging The Data,

Spreading

The Word

The Ghostwriters

In 1999, Johnson & Johnson had signed a contract with a company called Excerpta Medica. Its specialty was medical marketing. Its sub-specialty was producing ghostwritten, data-filled studies on the efficacy and safety of a client’s drugs, finding the right academic scholars to be listed as the authors and then placing the articles in prestigious academic journals.

Excerpta’s and Johnson & Johnson’s partnership with academics and the journals that publish them was not unusual. Over the last 20 years, research into the effects of specific drugs has become almost exclusively funded by drug companies that have an interest in the results. The government, through agencies such as the National Institutes of Health, sponsors generic research related to various diseases, but beyond that initial stage, most of the work is paid for by the pharmaceutical or biomedical industries.

In a detailed presentation to Johnson & Johnson, Excerpta outlined one of its key selling points: “Ensuring Vast Opinion Leader Access.”

“No other medical education company has the tremendous access to top opinion leaders that Excerpta Medica does … ” Excerpta promised. “Our parent company, Reed Elsevier, is the largest supplier of medical information in the world, publishing over 700 medical journals in almost every conceivable therapeutic area. Each journal has an editorial board composed of renown specialists throughout the world who are available to us as consultants, advisory board members, speakers, and in other capacities. We provide this significant access to all of our clients.” (The Excerpta connection to the giant Europe-based publisher would be severed in 2010, when it was sold to a unit of the giant advertising agency Omnicom.)

Now, in 2000, Excerpta began working on a plan to place dozens of Risperdal articles in medical journals. “Awareness articles” and “original reports,” of which a total of 39 were planned, would cost $22,000 each in fees, plus fees for the “authors.” Shorter pieces would be $9,000 each.

As Excerpta later explained when it presented its plan to Janssen executives, the goal was to publish clinical data and marketing that supported the use of Risperdal for mood disorders. “Overall, the plan supports risperidone’s market expansion into the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder and, more broadly, into the treatment of patients with mood disorders,” the presentation promised.

Significantly, one example of a “core message” piece, according to the Excerpta proposal, would be a scholarly article that conveyed the message that Gorsky and his team had decided that they needed to fend off attacks by competitors: “prolactin elevation sometimes seen with Risperdal treatment is not (directly) linked to clinical abnormalities.”

To that end, in August 2000, Excerpta’s Michelle Daniels emailed Dr. Robert Findling, a renowned child psychiatrist at Case Western Reserve University hospital (he is now director of child and adolescent psychiatry at Johns Hopkins), to ask if he would be a lead author of an article that would be based on the results of Risperdal studies involving children taking the drug over an extended period. The data was not in yet, but the working title was “The Safety and Efficacy of Open-Label Risperidone in Conduct Disorder in Mild, Moderate and Borderline Mentally Retarded Children Aged 5 to 12 Years.”

“You have been identified as the lead author to this manuscript,” Excerpta’s Daniels wrote, noting that she had attached a “preliminary outline for your manuscript.”

Findling agreed to attach his name to the article, but suggested that “some secondary analyses be performed in an attempt to identify risk factors for … prolactin increase.” How steadfastly he stuck to his guns is a source of controversy that continues to this day.

‘We Need To Be Proactive’

Excerpta’s safety/efficacy messaging strategy was consistent with a January 2001 email that Gorsky, then Janssen’s vice president of sales and marketing, sent to executives in New Jersey and Belgium (Janssen’s birthplace and still a major outpost). “While we cannot respond to each and every competitive jab … we should expect that we will be challenged on a number of fronts due to our market position … therefore we need to be proactive in expanding on our strengths (efficacy long and short term, agitation, weight gain, etc) and defending our weak spots.” The first “weak spot” Gorsky listed was “prolactin.”

Although the results of the clinical studies of boys and gynecomastia that were tabulated in November 2000 seemed to confirm that prolactin vulnerability, Gorsky would later testify that when he wrote this email three months after those results had come in he thought of prolactin as a perceived weakness because of competitive claims, not a real one.

Whatever he already knew about the discouraging prolactin data, Gorsky was certainly on top of his competitors’ potential vulnerabilities. The next day, a Janssen doctor wrote Gorsky saying that he had “spread the word” about the death of a patient enrolled in the trial of a Risperdal competitor drug.

Gorsky’s reply: “Good. … It sounds like we have taken the right steps.”

‘I Am Very Reluctant To Have These Data in the Public Domain’

In March 2001, Janssen doctors received the summary results of a study of Risperdal use among the elderly that was intended to get the FDA to include seniors with dementia on the label. The data revealed unmistakably that when compared to test subjects receiving a placebo, there was a statistically significant increase in what are called cerebrovascular adverse events, or CVAEs—including strokes.

One of the doctors reviewing the study said that the results should be publicized at an upcoming medical seminar. But a Janssen executive (not Gorsky) objected. “I am very reluctant to have these data in the public domain that soon,” this executive wrote to other members of the clinical studies team in a March 22, 2001, email. “You may have noticed that in the topline results there are substantially more [cardiovascular events] in the Risperdal group. These are of substantial concern to us. … I propose to keep this discussion in-house, though, until we have a better understanding.”

In May 2001, a Janssen statistician working on three elderly studies reported that in reviewing the first two and combining it with the third one that had been the subject of the March email, there was a statistically significant relation between taking Risperdal and suffering strokes and other CVAEs. In May, Janssen submitted that data to the FDA, as required by law. But the company continued not to make the information public until two years later, in 2003. (Data submitted to the FDA is generally not made public by the agency.)

Shielding the Sales Team

By now, the J&J scientists and the sales teams seemed to be functioning in alternate universes. The worse the data on the elderly got, and the worse the potential for the FDA reaction to it got, the more J&J seemed to intensify its sales effort. That same month, Janssen distributed a “Primer on Dementia” to its ElderCare sales force. The marketing team also created a section for a training manual called “Handling the Most Common Objections Voiced By Prescribers,” which told the sales reps to remind doctors that “Risperdal has an excellent combination of efficacy and safety.”

At a fall 2001 training session in Pittsburgh, one sample dialogue that trainers acted out for the group instructed the team to “Bridge to Risperdal” this way: “Doctor, as your patient’s disease progresses into the moderate to later stages of AD [Alzheimer’s Disease] and behavioral type symptoms become more prevalent, Risperdal offers superior efficacy, an unparalleled safety profile, and dosing flexibility tailored to the geriatric patient.”

These ElderCare unit sales materials were part of a separate plan for the geriatric market that also included 1,100 “Senior Care Seminars” nationwide, or 21 a week, for doctors whose patients were most likely to be elderly. The events, typically luncheons, would deploy 250 paid physician-speakers. Like the pediatricians getting Risperdal popcorn and Legos, these speakers were “whales” —doctors already prescribing large quantities of Risperdal.

Prescriptions written by the doctors who attended would be tracked by J&J not only to gauge the effectiveness of the sessions, but also to identify emerging whales so that they, too, might be offered paid speaking engagements.

At the same time, Janssen was pushing Omnicare to ratchet up its program to make Risperdal the drug of choice at the nursing homes where it ran pharmacies. At one point, after J&J found out that Omnicare had negotiated a similar, thoughwhich didn’t seem likely apparently not as favorable, deal with Eli Lilly and demanded that Omnicare cancel the Lilly deal, the pressure from Johnson & Johnson became more than the Omnicare executives were willing to tolerate.

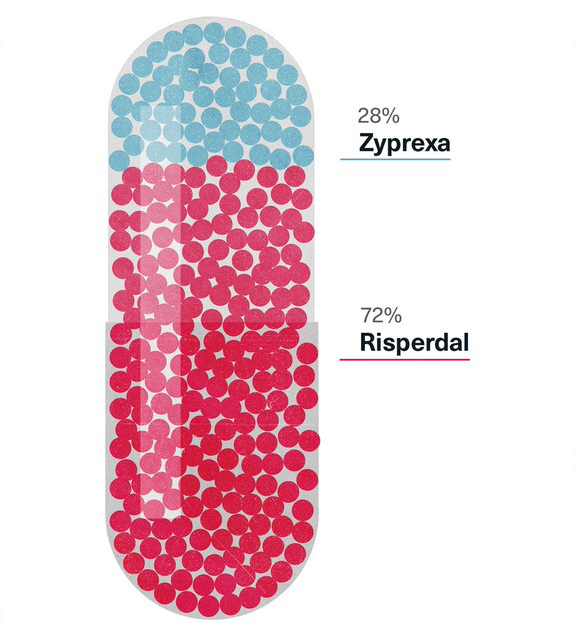

In a February 14, 2001, letter to Janssen Long Term Care Account Director Bruce Cummins, Omnicare senior vice president Timothy Bien pointed out that “Omnicare will spend $173,128,000 on J&J products in 2001,” compared to $126.8 million for Lilly products, and that “head to head, Risperdal enjoys a 72.3% market share in number of scripts with Omnicare,” compared to 27.7 percent for Lilly’s Zyprexa. Complaining that his company needed the “$3.5-4 million the Lilly contract represents,” the Omnicare executive concluded, “I am angry by Janssen’s stance. We all need to keep in mind the very successful relationship we have built together.”

There was no trace of the Credo in the exchange between J&J and Omnicare—nothing about the comparative quality of the drugs involved or their effect on patients.

Market Share of Risperdal and Zyprexa in Omnicare Prescriptions, 2001

Living Up to The Credo, Almost

On September 4, 2001, Janssen’s top development executives met to discuss a subject that might have heartened Robert Wood Johnson II and anyone else who believed in the J&J credo. It seemed as if the company was finally reconsidering its marketing tactics and was about to stop pushing Risperdal on elderly patients.

The headline of a PowerPoint presentation prepared for the meeting was non-committal: “Risperdal in BPSD”—Behavioral and Psychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. But the subhead was direct and seemed to signal an about-face from Johnson & Johnson’s drive to promote Risperdal off-label to the elderly: “The BPSD project shall be terminated as ethically, legally, and quickly as possible.”

The PowerPoint began by running through all the bad news—the various studies with negative findings and the fruitless data submissions to the FDA to get dementia treatment onto the label. It then outlined the steps that would have to be taken to ease patients currently in clinical trials of Risperdal off of the drug.

Next came a page entitled “Ethical/Moral” implications.

But it turned out that this was not about the ethical and moral implications of continuing to push Risperdal to the elderly. Rather, it was about the supposed ethical and moral implications of ending the elderly campaign, including the disruption to patients caused by the fact that Johnson & Johnson’s off-label marketing had been so successful that “over one half of all antipsychotic-treated dementia patients are currently using Risperdal in the U.S.”

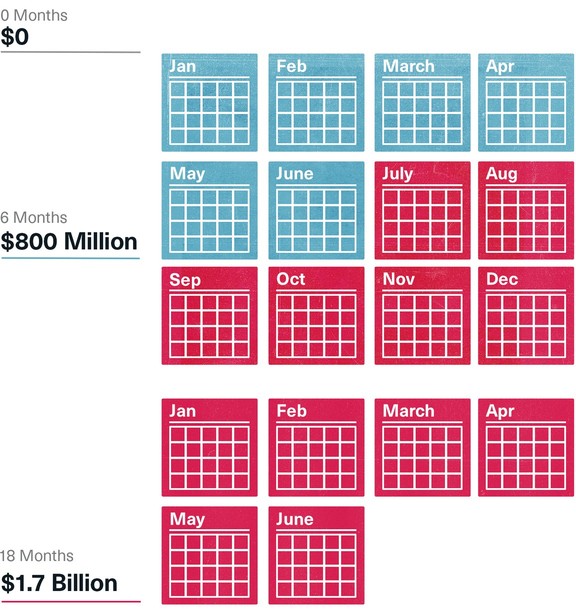

The numbers were tallied on another page. The cost of three alternatives—suspending the project for six, 12 or 18 months until some solution could be found that would improve the data—were estimated and compared to staying the course. Even the briefest delay aimed at getting better data would cost $800 million in sales between 2001 and 2010, and an 18-month delay would cost nearly $1.7 billion. And all of the estimates assumed they would get the data they needed, which didn’t seem likely.

The meeting ended with a decision by the numbers. The ElderCare campaign would not be cancelled or suspended. They would keep going and keep trying to persuade the FDA to allow the label to include treatment for dementia.

Estimated Cost of Delaying Risperdal Campaign to the Elderly

More Bad Breast Numbers

Soon after the meeting to deal with, and put aside, the concerns about the drug’s safety when taken by seniors, it became clearer that serious side effects in children might be an equally significant problem. The Janssen doctors and statisticians now had more complete results from the long-term study of children and adolescents using Risperdal. They confirmed that the claim on the current label that gynecomastia was “rare” (meaning that it occurred in fewer than one-tenth of 1 percent of patients) was understated by a factor of more than 50. The final tally was 5.5 percent of the boys.

The numbers didn’t dampen the sales pitch. In 2001, 1,106,000 prescriptions would be written for children and adolescents. “Discussed … proper dosing in children,” reported one salesperson. “Warned him about competition putting side effects out of context regarding R[isperdal] in children.”

However, not every sales rep was on the same page.

Doing The Wolf Howl

Victoria Starr, who everyone calls Vicki, had high hopes when she joined Janssen in the summer of 2001.

The daughter of a Nevada pharmacist, Starr, then 30, had always wanted to work in the industry. After getting a pharmacy degree from Washington State University and her pharmacy license, she went to work for Eli Lilly as a sales rep in and around her home in Portland, Oregon.

A roundtable “best practices” discussion turned into a primer from Starr's sales manager on “selling to kids, and telling doctors to give them smaller doses.”

In 2001, after she had been at Lilly for six years, Starr decided to leave. She was fascinated with the science and the promise of central nervous system (CNS) pharmaceuticals, and Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen unit had an opening in that division.

A short, outgoing brunette, Starr can be dead serious about business one moment and quick with a laugh the next. Janssen “might have been a little too straight-arrow for me,” she recalled, “with their car inspections and even checking out your driving record. But I thought they were serious about having people with pharmacy training sell doctors based on the chemistry of the drugs, the science of the nervous system, and all that.”

Her first meeting with the CNS Oregon division, in the fall of 2001, was not what she had anticipated. A roundtable “best practices” discussion turned into a primer from her sales manager on “selling to kids, and telling doctors to give them smaller doses,” she says.

“I’m a label kind of person,” Starr adds. “I like to talk to my doctors about the label, about receptors, about how the drug actually works. And there were no studies in these materials about any of that—just how we could sell to the symptoms. That it would calm kids down.”

Starr remembers that she felt sorry for one of her new colleagues, whose prospects were mostly pediatricians. “He kept asking what he was supposed to leave behind. … He was told to use the stuff from the binder, but not leave it behind, because at that time they still weren’t actually leaving that kind of material behind. They knew it wasn’t allowed.”

A few weeks later, Starr found herself at a national Risperdal sales meeting at the Boca Raton Resort & Club in Florida. Market share numbers were reeled off by region, with exhortations that 2002 was going to be even better. The markets for kids and the elderly were called out as special priorities, Starr says, “because that’s where they saw all the growth. With adults, you pretty much have to focus on the actual diseases—like schizophrenia—because adults don’t end up at the doctor getting drugs for acting up. But kids, or the elderly with dementia, do.”

At one point, to amp up the troops, the CNS sales chief asked everyone in the ballroom to do the “wolf howl.”

“Everyone broke out into this weird howl,” says Starr, laughing. “It was a cross between what you’d hear at a Super Bowl and at a religious cult. … It was kind of fun, great team spirit and all.”

‘Money on the Table’

Back at Janssen headquarters, Gorsky, who had just been promoted from sale chief to Janssen’s president, sent a November 2, 2001, email to a group of his top executives asking that they set a date to “review ‘Growth Opportunities.’ … These are similar,” Gorsky wrote, “to the ‘Money on the Table’ exercises we conducted last year … that we feel can generate top line [revenue] growth in the 2002 and 2003 timeframe.”

Gahan Pandina, Janssen’s assistant director of CNS clinical development, then suggested in a follow-up email that this might “be an appropriate forum to discuss the J&J Center idea with Dr. Biederman.”

Pandina, a top Gorsky lieutenant in the Risperdal effort, was referring to an idea that Joseph Biederman, the star Massachusetts General/Harvard child psychiatrist, had recently pitched to Janssen. The doctor was apparently over his earlier piques about Johnson & Johnson brushing off his 1998 research proposal or being slow to deliver that $3,000 honorarium check. As another email picking up on Pandina’s suggestion explained, Biederman had recently “approached Janssen multiple times” to propose that Johnson & Johnson finance a center to study bipolar disorders in children and adolescents at Massachusetts General Hospital.

According to the email, “the rationale of this center is to generate and disseminate data supporting the use of risperidone [Risperdal] in this patient population.”

By March 14, 2002, Johnson & Johnson had deposited the first $500,000 of what would be $2 million into an account set up for the center by Mass General—and Biederman was sitting at a kick-off meeting with a Janssen team to discuss the center’s plans.

Biederman then quickly took to the speaking circuit to push the center’s agenda. In an upbeat email, Pandina described a three-day educational seminar Biederman conducted for more than 1,000 physcians in child psychopharmacology and pediatric bipolar disorder:

“Dr Biederman was very well-received by the group. The validity of his diagnosis of pediatric mania was completely accepted and his diagnostic techniques deemed to be excellent. He was very balanced in his approaches to treatment and not perceived to be aligned with any company in particular.”

Continuing his report, Pandina told his colleagues that although Biederman had not been “perceived to be aligned” with any drug company, the doctor had managed to get a dig in at Risperdal’s main competitor:

“Evidently, he made quite a point regarding the metabolic issues related to olanzapine [the chemical term for Eli Lilly’s rival Zyprexa] to the extent of stating that this drug should not be used in the treatment of children and adolescents, highlighting the issues with published data.”

The Quest for ‘Reassuring’ Data

It was unclear what Zyprexa data Biederman could have been referring to. In fact, the Risperdal data that J&J officials were now reviewing back home was causing heartburn. In late February, a new analysis of clinical data seemed to show that there was a relationship not only between Risperdal and raised prolactin levels, but, more crucially, a relationship between raised prolactin levels and instances of gynecomastia in young boys.

Although Johnson & Johnson never acknowledged it, the company, as well as its competitors, already knew from multiple studies that Risperdal alone caused highly elevated prolactin levels even at the recommended low doses for children. And the company already had studies seeming to show an alarming rate of gynecomastia in children using Risperdal.

But the most important question—the one for which new data was now being tabulated—was whether these raised prolactin levels were a temporary and harmless condition, or whether they actually caused diseases such as gynecomastia.

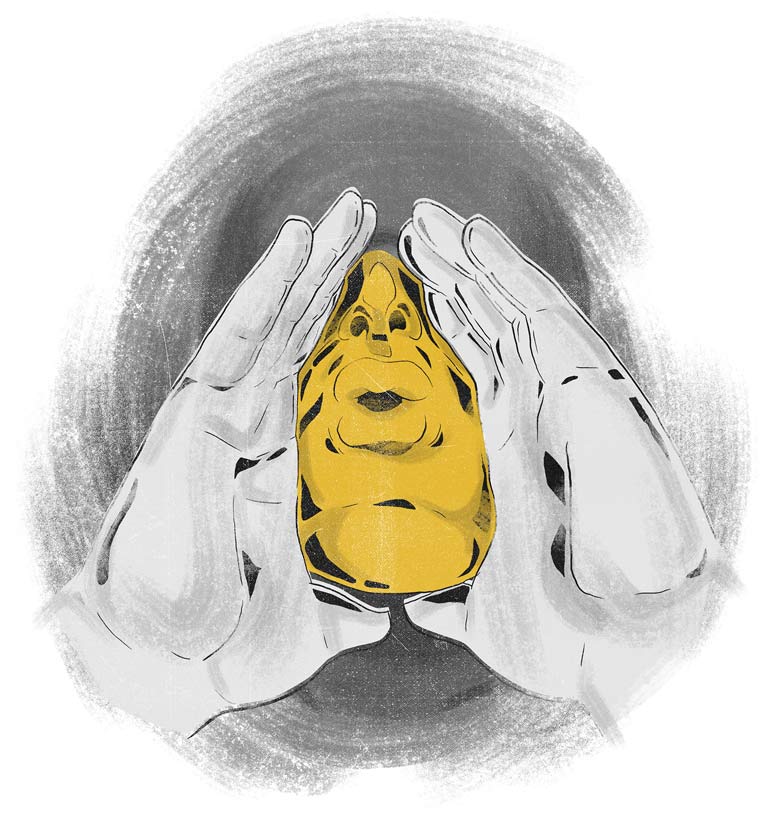

Proving a Cause

The best science—and potentially the best legal case against Risperdal—would not only require determining whether a significant number of boys given Risperdal end up with gynecomastia, compared to those who do not get the drug. Some intervening factor would also have to be found that made it clear that this was not a coincidence. “A” might be associated with a high incidence of “B,” but showing an association wasn’t proof that “A” caused “B”. Some kind of causal relationship had to be shown.

A Causal Relationship Between Risperdal and Gynecomastia

That is what made the prolactin and gynecomastia data so important. Could it be shown that raised prolactin, which Risperdal was known to cause, could in turn be the cause of gynecomastia?

Conversely, showing the absence of any causal relationship would be the best defense that Risperdal may be associated with gynecomastia but does not cause it.

This causal relationship data—whether there was any link between raised prolactin and gynecomastia—was the data that was going to be used in the paper that Excerpta Medica had recruited Dr. Findling to author about the long-term safety of Risperdal.

The goal, expressed in notes and emails referring to multiple meetings of Janssen scientists and sales and marketing people, was to trump their competitors’ claims and prove that there was no causal link between Risperdal and gynecomastia. As an August 21, 2002, email from Pandina circulated to the “Pediatric Publication Team” put it, “If we can demonstrate that the transient rise in PRL [prolactin] does not result in abnormal maturation … this would be most reassuring to clinicians.”

Accordingly, the minutes of a fall 2002 meeting of the Risperdal Children and Adolescents Advisory Board—a group of Known Opinion Leader-doctors, who were paid $2,500 each to attend—reported that the doctors were promised that the new data would be “reassuring.” According to the minutes, the “KOLs” were also being trained to handle questions from the media about the reassuring data—data that had not yet been produced.

$2 Million to Mass General / Harvard to Advance the ‘Commercial Goals of J&J’

The 2002 budget earmarked $1.75 million for the Known Opinion Leaders’ paid attendance at advisory board meetings, their subsequent speaking appearances at doctor symposiums and related expenses for “education” targeted at doctors who treat children and adolescents.

That was apart from the $2 million that would ultimately be spent on the salaries, studies, conferences and other activities of Biederman’s Center for Children and Adolescent Bi-Polar Disorders.

An annual report on the work of the Biederman Center during 2002 presented by Janssen’s marketing staff to justify the expense bluntly listed its value this way:

“An essential feature of the center is its ability to conduct research satisfying three criteria: a) it will lead to findings that improve the psychiatric care of children; b) it will meet high levels of scientific quality; and c) it will move forward the commercial goals of J&J.”

The next paragraph added a clear call-out to Biederman’s value: “Equally important to effective use of medications is the demonstration of the validity of disorders.”

Those were the conduct disorders the FDA had repeatedly refused to ratify.

Austin Takes His Medicine

On June 20, 2002, a 7-year-old boy from Alabama named Austin Pledger took his first dose of Risperdal—0.5 milligrams dropped into a glass of water.

A month before, a J&J salesman had made his first call on Jan Mathisen, a pediatric neurologist who was treating Austin. The salesman talked with Mathisen about the benefits of using Risperdal for children with behavior disorders and left him with samples—140 starter packages.

In early June, a second J&J salesman visited with Mathisen and left more samples. Between June 2002 and November 2004, that salesman would make 20 more visits, dropping off thousands of child-sized doses of the antipsychotic.

Around Austin’s third birthday, his mother, Benita Pledger, had taken him to Illinois to visit her sister, who drove a school bus. She took Austin to ride the bus with her one morning. When she returned home, she told Benita, simply, “I think Austin is autistic.”

“I was shocked,” Benita Pledger recalls. “I mean, what is that?”

Her sister explained that Austin had seemed disconnected from the children on the bus, and that he hadn’t responded to her sister at all—“he just repeated back whatever she said to him.”

Austin was officially diagnosed with autism by a local pediatrician as he was about to begin kindergarten. Arrangements for a special education program were made at the local elementary school. “He could recite the alphabet from a poster at school, sing songs in English or even Spanish that he had heard once,” his mother recalls. “But he couldn’t read ‘cat.’”

Austin would erupt suddenly into fits of apparent confusion or rage, banging his head against the floor, biting his hands and arms or even hitting some of the other special education children. “He couldn’t handle any change,” his mother explains. “Even moving from one room to another might set him off.”

One day at kindergarten, “the school lost him,” Benita Pledger recalls. “He just walked out.” After that, she changed the hours she worked as a machinist at a paper mill. Then she quit altogether. That way, she or her husband—who operated a car repair shop out of a garage less than 100 yards from the family’s modest home—would always be available to check on Austin at school and be with him when he got home. “We had tried 13 years to conceive Austin,” Benita Pledger explains. “He was a gift.”

In April 2002, as Austin was nearing the end of first grade, Benita met with his prospective second grade teachers and the school aides who would be working with him in the fall. A teacher’s aide told her that her own sister had a troubled child and had consulted a specialist—Birmingham pediatric neurologist Jan Mathisen—who had helped enormously. Maybe she should take Austin to see him.

The Pledgers were skeptical, especially Austin’s father, Phillip. “I figured we’d drive into Birmingham [about 50 miles] to see this guy,” he recalls. “But if he prescribed some drugs right off the bat, that would be a negative. We weren’t looking for drugs just to calm him down.”

Mathisen spoke of Austin’s illness in a way that rang true to parents who treasured their son’s bright moments as much as they dreaded the darker times, and had struggled to reconcile the two. “He explained that Austin cannot read any cues,” Benita remembers. “That it’s as if this wonderful, sweet boy who knows so much has landed in a foreign land and doesn’t understand the language and the social cues. It mystifies him and then it frustrates him.”

Mathisen did not prescribe medication. “He told us he had started giving some patients something and it seemed to work, but he did not push it on us,” Benita says. “He told us to think about it.”

By mid-June, the Pledgers had become more troubled by Austin’s frequent outbursts. Benita brought Austin to Mathisen again on June 17, this time to talk more seriously about medication.

The drug was called Risperdal, the doctor said. It would not “cure” autism, he explained, but it might ease the rough edges of Austin’s frustration.

As for side effects, Mathisen said that Risperdal would likely cause some weight gain the way other drugs of its kind did. “We were okay with that,” Benita Pledger explains. “Austin was pretty thin, and I’m big on healthy foods, so we thought we could handle that.”

Within a few days, the Pledgers had decided to give it a try, and on June 20, 2002, Benita drove back to Birmingham to get Austin’s first prescription and pick up some samples to get him started. Both Austin’s visits to Mathisen and his Risperdal prescriptions were paid by Medicaid, the federal-state program that in Alabama supplies health insurance to families living below the poverty line.

That night Austin’s parents were still nervous. Unlike most consumers, they had taken a copy of the multi-page FDA “label” from the doctor and tried to read their way through it.

This was the label approved in 1994. It did not say anything about Risperdal’s possible side effects when taken by children. It mentioned prolactin-related side effects (although using more technical medical terminology) as “rare,” meaning that it was observed in no more than one-tenth of 1 percent of patients.

Still unsure, Benita dialed the Johnson & Johnson hotline number listed on the label. According to company records later introduced in court, she left a message with her name and number, saying she was wondering how Risperdal helps children with autism and what the “dangers” were.

She and her husband then decided to go ahead and give Austin his first dose.

A few days later, after not having heard back from J&J, Benita called the hotline again, with a specific question about whether Risperdal could be taken with an allergy medication that Austin was also using.[1] This time, she spoke with someone who told her to consult her doctor about that. She did not repeat her first question about side effects, although she did provide her address when asked.

The hotline operators didn’t know it, but the questions Benita was asking about side effects had been a source of intense concern among Johnson & Johnson scientists and executives when they huddled in a hotel suite less than a week before.

[1] The company would later assert that a Johnson & Johnson staff person did try to call her back, but got no answer and that the phone had no voicemail recorder. Benita would claim that she was home during almost all business hours and never got a call. She also said she never got a mailing about side effects from Johnson & Johnson despite having left her address during her second call.