Trouble

A Pest in Pennsylvania

Allen Jones had had an uneventful career working as an investigator for the Office of Inspector General in Pennsylvania. But in July 2002, he noticed that a new account had been set up to receive payments from the Janssen division of Johnson & Johnson. What was that for?

The bank account, he was told, was meant to cover travel expenses for health department officials so that they could examine a program that their colleagues in Texas had told them about. It seemed like a promising way to create modern prescription guidelines for Pennsylvania’s use of antipsychotic drugs in state mental institutions and among Medicaid patients, including children, the officials explained to Jones.

By September 2002, Jones says, he was “pretty sure something was wrong here.” One of the state’s pharmacists, he found, had been accepting speaking fees in addition to travel expenses. J&J was also paying to reimburse state employees for conducting seminars about the program throughout the state. By October, Jones had confirmed that the program—called PMAP in Pennsylvania, just as it had been called TMAP in Texas—was going to start using the guidelines, called algorithms, in January.

Jones began pestering state bureaucrats about why they were switching to all of these more expensive drugs, and why were they allowing prescriptions to people who had never been given medication before. Frustrated at being stiff-armed and told by his bosses to confine his investigation to the pharmacist who seemed to have taken personal fees and not reported them, he was soon taken off the assignment, and, he claims, “given a desk completely out of the way, with nothing to do.”

Jones didn’t waste his spare time. He began copying documents to take home. And he began thinking about finding a lawyer.

Vicki Starr Goes Rogue

By the fall of 2003, Risperdal sales rep Vicki Starr was ready to quit. She had been working for Janssen in the Northwest region for a little over two years. During that time, her green manual full of sales material that at least devoted some attention to how the drug treated schizophrenia had been replaced, she says, by a “red binder full of material that directed the sales staff to sell to a full spectrum of symptoms that could be related to just about any mental health condition.”

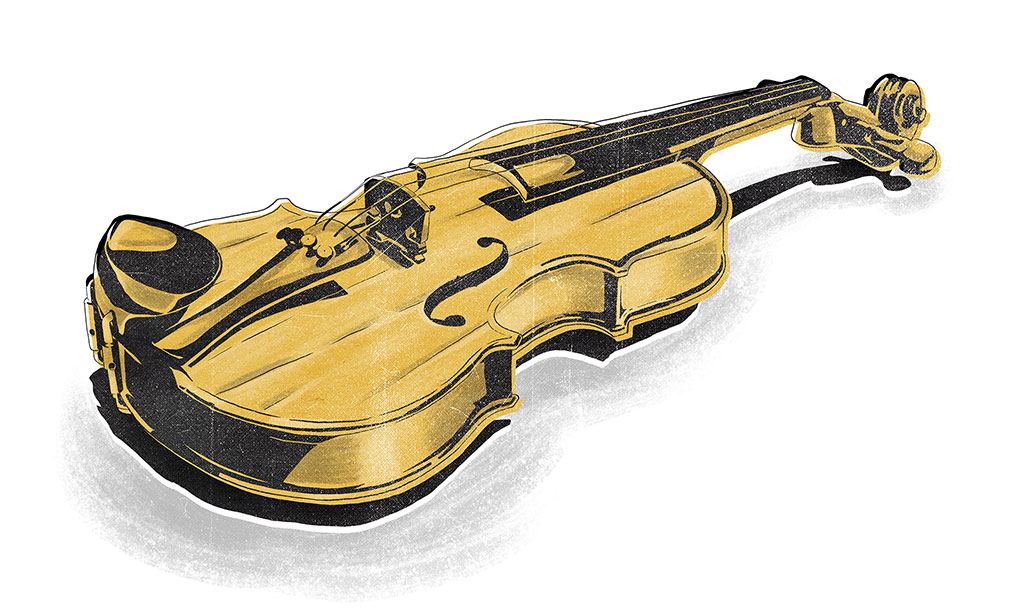

Lawyers planning to sue Johnson & Johnson would later refer to a sales aid depicting a girl playing a violin as the “Yo-Yo Ma” brochure.

To drive home that idea, some of the new materials, she says, “had pictures of high-functioning people. There was a girl with a violin.” Lawyers planning to sue Johnson & Johnson would later refer to this sales aid as the “Yo-Yo Ma” brochure.

Starr knew that the company had set up a separate ElderCare sales unit, and she had commiserated with one of the sales reps in her region who had been assigned to it. Starr had also been instructed to talk up the drug’s benefits for geriatrics when she called on mental health institutions or Veterans Affairs hospitals, which had elderly patients. Janssen’s targeting of the elderly bothered Starr, but she dreaded her calls with pediatricians the most.

“Some [pediatricians] told me about side effects they were seeing in kids,” she says. “I felt bad. … But to Janssen it was like this crazy old uncle in the attic. You don’t want to talk about it or deal with it. … Some were describing side effects in a way that was different from reading about percentages in a pharmacy book. But I was just as worried about the ones that were not seeing side effects because they might not have been looking. … Doctors wouldn’t know what the drug was doing unless patients complained.”

There was also a more personal element: “I had one family member and one close friend who had children taking Risperdal. One of them was 3 years old. I couldn’t interfere. It wasn’t my place, but it was something I kept thinking about.”

One afternoon in October, Starr called her friend Hector Rosado, a Lilly salesman she had worked with whom she considered a mentor.

Starr told Rosado a bit about her dissatisfaction with the sales she was being forced to make.

“I’m ready to quit,” she told him. “Do you know of any openings at Lilly?”

“Wait. Don’t. You need to talk to me,” Rosado shot back. “Let’s meet tomorrow. I think you should see a lawyer. I’ll explain.”

The next day, they met at a Starbucks in Eugene, Oregon. Over coffee, Rosado introduced Starr to the world of Big Pharma whistleblowers.

A Civil War Law Stalks Big Pharma

During the Civil War, concern over corruption in the Union’s procurement of war supplies moved Congress to pass the False Claims Act, which allowed citizens to bring what was called a qui tam action—a Latin phrase that loosely translates to “he who brings the action for the king as well as himself.”

In plain English, the law allowed citizens to sue parties that had defrauded the government, on behalf of the government. And it provided an incentive: The citizen plaintiff, called a “relator,” would be entitled to a share of the amount, if any, that was recovered. The bounty awarded by the judge overseeing the case was usually 15 percent to 25 percent.

The statute fell out of use after Reconstruction, until Congress passed the False Claims Amendments Act of 1986, which set rules for when the Department of Justice could intervene and join the relator in the case. Through the end of the 20th century, the revitalized law was mostly used in cases alleging fraud in conventional government procurements, such as those involving the Pentagon. Employees of defense contractors could blow the whistle and be paid for their efforts if their suits were successful.

Beginning in 2002, more traditional plaintiffs lawyers—who usually pursue claims against corporations for injuries suffered by consumers because of faulty products, such as cars, tobacco or drugs—began to look at possible false claims related to Big Pharma.

The potential payoff had to do with the fact that so many prescriptions are paid for by the government. Off-label sales of Risperdal for someone on Medicare or in a veterans’ hospital might merit a federal false claim. The sale off-label to someone receiving Medicaid, which is paid for with both state and federal funds, might constitute a false claim victimizing both the federal government as well a state government, because many states had enacted their own qui tam false claims acts.

But with qui tam suits still being relatively obscure, how were the plaintiffs lawyers supposed to find the whistleblowers?

Big Ego, Big Causes, Big Money

Stephen Sheller, a rumpled figure who looks younger than his 76 years, made his name and his fortune fighting big tobacco and other deep-pocketed corporations. Living proof that trial lawyer with a big ego is redundant, Sheller has a garish website, full of testimonials and links to headlines and TV clips lionizing him as a champion of the little guy.

Sheller is forever eager for a new case, and, it seems, not simply because of the money. From his days defending Black Panthers, he has always seemed to get a kick out of fighting for causes. In 2001, his bottomless capacity for outrage, his quest for a good cause and, in this case, his devotion to family (two daughters, whom he brags on with no prompting, work at his firm), came together perfectly. One afternoon, the local police department impounded the car one of his daughters was driving for having expired registration and left her in a sketchy neighborhood. Sheller turned that into a class-action settlement against the department after charging that their abandonment of drivers was against police policy.

In 2001, Sheller got a tip from a Florida woman who had seen him on television. She claimed that samples of Prozac had been mailed unsolicited to her son. Sheller snooped around the way good plaintiffs lawyers do and soon found that Prozac’s manufacturer, Eli Lilly, was apparently sending the samples all over Florida. Within a few months, Sheller was back on television—with a client who was wearing a hood to hide her identity—talking about the suit they had filed against Lilly for its allegedly indiscriminate Prozac marketing.

News of that traveled to California, where a Lilly sales rep ended up contacting Sheller to talk about more alleged Lilly shenanigans on the West Coast. That, in turn, led to five Lilly sales reps contacting him in 2003 about Zyprexa, Risperdal’s Eli Lilly competitor. They told him that Lilly was selling the drug off-label to geriatrics.

By late 2002, Sheller had filed a qui tam charging Lilly with false claims, through illegal sales of Prozac, Zyprexa and two other drugs to patients whose prescriptions were paid for by the government.

Qui tam suits are governed by a strange set of rules that require the plaintiffs to file their cases under strict secrecy until the federal government decides whether to intervene. If the government does intervene, the cases are easier to prosecute because the government has subpoena power and superior resources. If the government declines to join the case, the “relator” (the private plaintiff) can proceed on his or her own, and will get a higher fee because of all the extra effort and resources required.

In theory, the government has only 60 days to decide whether to step into a qui tam case. In practice, judges allow those decisions to drag on for years. That means that the case—and the employee’ s role as a whistleblower—can stay secret for years.

One of Sheller’s whistle-blower plaintiffs in the Lilly suit was Hector Rosado—Vicki Starr’s former mentor whom she had called that day in October 2003 for advice about a new job. Instead, Rosado had told her to contact Sheller.

Lottery Dreams

Vicki Starr was “stunned and scared,” she says, when Rosado told her about the lawsuit and the federal agents who were pumping him for information and documents. “He said that there might be some money in it, but that that was all speculative. He just felt he was doing the right thing,” she says, providing an impossible-to-confirm rationale that people cynical about trial lawyers and whistleblowers will undoubtedly dismiss.

The day after Starr met Rosado at Starbucks, she got on a conference call with his lawyers—Sheller and Michael Mustokoff, a former prosecutor who had become a partner at a Philadelphia firm that more typically represents corporate clients. Sheller had brought Mustokoff in on the qui tam drug cases once he began to sense their potential scope and realized that they typically begin as criminal investigations.

Sheller signed up Starr as his client. She would pay nothing, but he (and other lawyers, such as Mustokoff, with whom he split his fees) would get 33 percent of whatever winnings she got. Sheller and Mustokoff then negotiated a cooperation deal with federal prosecutors that assured that Starr could not be held responsible for any off-label selling she had done.

A J&J manager told one sales rep to be sure to include “lollipops and small toys” in the sample packages she gave to doctors.

“At first, we had lottery daydreams,” recalls Starr’s husband, Jason, who works in real estate. “But the lawyers never mentioned any numbers.”

Through fall 2003 and into the new year, Vicki Starr remained at work. She also began providing her lawyers with sales materials and other information about her employer. They packaged it up and passed it on to the prosecutors they were trying to seduce in the Philadelphia U.S. attorney’s Office. The documents were enough to get the prosecutors interested; they were already pursuing Sheller’s case against Lilly and were establishing their office, along with the U.S. attorney’s office in Boston, as the place to go for drug company qui tams.

Back to School with Risperdal

Meanwhile, Johnson & Johnson was embarking on a 2003 “back to school” campaign (a district manager’s sales report actually called it that) to launch its M-tab version of the pill. M-tabs would dissolve in a child’s mouth and, presumably, quickly control classroom behavior problems. In San Antonio, a manager told his salespeople to hold ice cream parties in pediatricians’ offices to celebrate the launch. Another manager told a rep to be sure to include “lollipops and small toys” in the sample packages she gave to the doctors she called on.

Sweeping the Files

By January 2004, Vicki Starr had had enough of being a mole. From the moment she had crossed the line and talked to the lawyers, she had wanted to quit, she recalls. So she found a job working for a company that operated pharmacy operations for nursing homes in the Portland area.

But first Starr did a sweep of everything she could find at Janssen to send to Sheller. Every sales brochure, interoffice strategy memo and office manual was loaded, she says, “into a huge box and shipped off to Philadelphia.”

Sheller had told Starr that he was preparing to file the suit, and that its prospects looked promising. She sensed that things might be resolved quickly, or at least that her role as a whistleblower would soon no longer be under wraps. She had told only her husband and parents about the world of lawyers, federal agents, debriefings and document hunts that Hector Rosado had introduced her to. No one else knew, including close friends, many of whom worked in the industry.

Starr worried that her friends in the industry would shun her.

“The whole thing was really making me nervous, creeping me out,” she recalls.

Almost from Starr’s first day at her nursing homes pharmacy job, the unsuspecting former Janssen colleague who had helped her get the new position began trying to sell Starr on stepping up her company’s Risperdal prescriptions. She knew, of course, that the drug wasn’t supposed to be given to seniors. But she played along, listening to the pitches, taking notes, then telling her lawyers.

At one point in March 2004, as Sheller was putting the final touches on the qui tam suit that he would file a month later, Starr was flown to Philadelphia to help her lawyers. When she had first gone over to the other side, Starr worried that what she was doing would jeopardize her pharmacy license. That somehow it would be seen as unethical. Or that her friends in the industry would shun her.

Now she felt better. The sessions with the lawyers, during which she got to spell out in detail the wrongs she believed she had witnessed, convinced her she had done the right thing, and that things were going to end well.

It was a friendly, upbeat discussion. Everyone in the room, of course, was on the same side.

Wired

One day in April 2004, Starr was in San Francisco for a three-day seminar on elder care. The night she arrived, she recalls, she saw that Johnson & Johnson was “sponsoring a whole breakfast devoted to using Risperdal in elder care.”

She called one of her lawyers. “You’re not going to believe this,” she said before reading him the invitation.

Almost immediately, Starr got a call from a federal agent working her case. “We’re going to have agents meet you, and wire you up,” he told her.

At 6:00 on the morning of the breakfast, Starr told the woman sharing her hotel room that she had to go down to the business office to fax some documents. Instead, she took the elevator to another floor, knocked on the door of a guest room and was greeted by a female FBI agent who flashed her credentials and asked Starr to remove her blouse.

The agent taped a credit-card sized transmitter to the middle of Starr’s chest. “If you want to say something private, you have to whisper,” the agent warned. “If you have to cough, turn away. This thing picks up everything.”

“I was so nervous,” Starr remembers. “This was beyond anything I had imagined.”

A few weeks later, Starr was wired again for an “education” luncheon J&J was sponsoring at a nursing home. When she got there, she found that the event had suddenly been cancelled, with no explanation.

“I thought maybe they were on to us,” Starr recalls. It was at about that time that she got what she thought was a “fishing expedition” from a former Janssen colleague with whom she had not been close. Out of the blue, he texted her, asking simply, “What’s up.”

By now, Sheller had filed his qui tam suit in federal court in Philadelphia, and a judge had approved Starr’s wearing of a wire at that San Francisco conference. However, both court proceedings were secret. There was no reason to believe Johnson & Johnson knew that investigators were circling.

Making Trouble in Texas

By November 2003, investigator Allen Jones was suing his bosses at the Pennsylvania Office of Inspector General. He claimed that they had frozen him out after he began investigating the algorithm campaign. But he wasn’t finished.

Jones had first consulted lawyers in Washington who referred him to a scrappy plaintiffs’ law firm in Texas. That firm realized the potential qui tam value of cases claiming that the entire scheme— TMAP in Texas, PMAP in Pennsylvania—was a plot to extract millions in Medicaid “false claims” from state and federal treasuries. However, the lawyers decided they were not equipped to handle a claim this big against a company like J&J, let alone on a contingent basis, under which they would have to front all the costs until they won (if they won) a verdict or settlement.

By the end of 2003, Jones ended up with Thomas Melsheimer, a well-known Dallas trial lawyer at the firm Fish & Richardson. Melsheimer had won big verdicts for defendants, as well as plaintiffs, in cases ranging from antitrust to insider trading to bank fraud.

Melsheimer set his sights on recruiting a key partner: Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott. Texas has its own version of a qui tam false claims law, and Melsheimer hoped he could entice the attorney general’s office to join the fray. Across the country, whether state attorneys general are Republicans, like Abbott, or Democrats, they generally see headline cases in which they crack down on big corporations as helpful if the want to move up politically. (Abbott is now governor of Texas.)

Melsheimer and lawyers from his office immediately began preparing their case, using the documents that Jones had been gathering. Occasionally, they would tease Abbott’s office with the best material. At the same time, Jones began, as he puts it, “seeding” the upcoming litigation with national publicity. On February 1, 2004, about two months before Vicki Starr was wired in San Francisco, The New York Times published a long article headlined “Making Drugs, Shaping the Rules.”

It had now been almost 10 years to the day since Johnson & Johnson had launched Risperdal. This was the first major news story that raised questions about how the company had turned the drug into its top seller.

“Since the mid-1990’s, a group of drug companies, led by Johnson & Johnson,” the Times reported, “has campaigned to convince state officials that a new generation of drugs—with names like Risperdal, Zyprexa and Seroquel—is superior to older and much cheaper antipsychotics like Haldol. The campaign has led a dozen states to adopt guidelines for treating schizophrenia that make it hard for doctors to prescribe anything but the new drugs. That, in turn, has helped transform the new medicines into blockbusters. ... Texas, for example, says it spends about $3,000 a year, on average, for each patient on the new drugs, versus the $250 it spent on older medications.”

The Times story then introduced Jones, who was pictured in the article sifting through documents.

Seven weeks after the Times story appeared, Melsheimer filed Jones’ suit.

“Through TMAP, the drug industry methodically compromised the decision-making of elected and appointed public officials to gain access to captive populations of mentally ill individuals in prisons and state mental hospitals,” Melsheimer’s complaint charged.

Significantly, Melsheimer’s focus was on Risperdal being an overpriced and no better substitute for drugs like Haldol, not on the company’s efforts to promote Risperdal to patient populations and for behavior disorders that were outside what was allowed under the label.

Again, because this was a qui tam suit, Johnson & Johnson had no way of knowing about it yet. Yet everyone involved in Risperdal had to have read the New York Times article, which had reported that federal healthcare officials were investigating Jones’ charges. In fact, a Janssen spokesman was quoted in the story. He said that his company “did not participate in nor influence the content or the development of the guidelines.”

Soon, the accusations and denials would involve more than marketing plans and conduct by state officials. The story was about to include the patients, too.