The Verdict

… And ‘Moving On’

‘Very Full, Pendulous Women’s Breasts’

The following are excerpts from Tom Kline’s closing argument for the plaintiff:

- Ivo Caers confirmed for us Table 21 was never reported to the FDA. … We know now what’s behind the tables: The little girls with the lactating breasts … and the little boys even under ten who have gynecomastia. My word.

- And when Dr. Kessler told us, ‘Red flag. This isn’t cherry picking.’ When a pharmaceutical company acting reasonably and prudently has this kind of data, they investigate it, they report it, they tell the FDA. They tell the doctors. They tell the world. They don’t just go on selling, selling, selling, selling the drug. … Oh, and giving it away in doctor after doctor’s offices.

- Janssen [said] to the FDA: ‘A review of the safety information did not show a correlation between prolactin levels and adverse events that are potentially attributable to prolactin.…’

- The opposite of Table 21.

- And by the end you see what happened. He had full breasts … very full, pendulous women’s breasts, and today, after losing some weight, has the rock in the sock. Size 46 double D breasts. … Tell me anybody in your life that has size 46 double D women’s breasts, any boy that you know who has size 46 double D women’s breasts that he got from puberty. …

- Now look at him. Behind that beautiful smile … is the remnants of this horrible drug. All they had to do was tell the truth, the full truth, and nothing but the truth. Like when you put your hand on the Bible.

- My word, he had breast buds, they developed into women’s breasts.

- So please, please remember that in this case it’s really important for Austin, and through his mother, Benita. And I have just been the person who has had the good grace to be the one to argue to you.

‘Don’t Be Swayed by the Crowd; Stand on Principle’

The following are excerpts from Diane Sullivan’s closing argument for the defendant:

- Thanks for sticking with us. It’s been a long couple of weeks, and you folks have come in here in the snow, in the rain, in the ice and even during the Polar Vortex, and we are grateful for your service. I am humbled by your service. You have come in here and served with grace and dignity, and great patience, even when the lawyers were all acting like children. …

- You learned that it took ten years from the time that Risperdal was discovered in the lab to do all of the testing in the lab, and animal testing, and to satisfy all the FDA requirements to test it in people. … And you heard the doctors and scientists from Janssen who talked about the fact that they know … they have a big responsibility to patients. They know that patients depend on them to get it right, to do the hard work and to do the science. …

- And you might have remembered when Dr. Caers, the scientist and doctor from Belgium, was on the stand and Mr. Kline was cross-examining him, and he said to Dr. Caers, ‘Dr. Caers, you ran the show … at Janssen in terms of drug development.’ And Dr. Caers said, ‘No, no, no, sir, it’s not a show. Discovering and developing medicines, it’s not a show. It’s hard work, and we take that very, very, very seriously.’ …

- But I submit to you that some of what you saw in this courtroom was show. …

- What did your common sense tell you when you heard that this lawsuit wasn’t started because a doctor told Mrs. Pledger that Risperdal caused a problem in her son? That this lawsuit wasn’t started because Mrs. Pledger or her son had any complaints to any doctors at all, but that this lawsuit started because Mrs. Pledger saw a plaintiffs’ lawyer’s TV commercial—1-800…

- And what did your common sense tell you when you heard that the only expert who could support their case that Risperdal caused Plaintiff’s enlarged breasts wasn’t an endocrinologist at all. I mean, we are in spitting distance of four major hospital systems. … They couldn’t find an endocrinologist not only in Philadelphia, they couldn’t find an endocrinologist who specializes in hormones anywhere in the country, anywhere in the world to support their case.

- The only expert they brought to say that Risperdal caused Plaintiff’s gynecomastia was a cosmetic plastic surgeon … who, as you heard, on his website is better known for turning Philadelphia into the penile enlargement capital of the world. …

- Now, Mr. Kline stood here and he told you we are going to talk about the facts and the evidence. I have been doing this a long time, not as long as Mr. Kline, and I have never seen a closing argument where the lawyer doesn’t show the jury a single piece of evidence. He stood here and he talked to you and he gave his version of the evidence, but he didn’t show you any. …

- What Dr. Mathisen saw, and what was on the label … was that—heads up—safety and effectiveness have not been established in children. …

- And then Mrs. Pledger claims—and, you know, you can’t blame a mom, a mom would say, ‘Yeah, if I had known something I wouldn’t have subjected my kid to a risk.’ But you have to test that against the evidence. She claims had she known about any risk of gynecomastia … she wouldn’t have allowed her son to be on this drug. Well, Dr. Mathisen didn’t tell her, but the truth is, she has got her son on another drug now that has far worse risks. …

- So while Mrs. Pledger says she wouldn’t have let him take Risperdal had she known about the risk of gynecomastia, I am not sure that it adds up. …

- And so the science just doesn’t support what they are arguing here, and that’s probably why they couldn’t find a single endocrinologist anywhere in the country to come in and support their case. They had to have a $20,000-a-day cosmetic surgeon, who admitted he doesn’t know anything about hormones, doesn’t do any research in hormones, and testified, yeah, like pornography, I know it when I see it. …

- I am going to briefly talk about this accusation and this Findling paper, this 8 to 12 week analysis. And I submit to you, it’s the height of cherry picking. …

- You have had a hard job, but have common sense, and you folks have struggled to pay attention. We are all boring. And we appreciate it. …

- [S]ometimes it’s easy to say let’s give him a little money, or let’s give him money and get out of here. But if you don’t believe the plaintiffs have proved their case, stand your ground.

- Do justice. Put them to proof.

- Don’t be swayed by the crowd. Stand on principle.

- And use your common sense. If Risperdal really caused Mr. Pledger’s gynecomastia, why is the first [person] to tell them that a lawyer, not a doctor? And if Risperdal really caused plaintiff’s gynecomastia, why do they get www-dot-whatever as their only expert?

- On behalf of the folks at Janssen, we appreciate your service, and I wish you the best in deliberations.

After the lawyers had finished on Thursday, February 19, Judge Djerassi gave the jurors that Friday and the weekend off.

We thought that Kline did a really good job communicating with us,” says the jury forewoman. “Sullivan tried to, but she was too harsh at times. She badgered people, and kept going around and around when she questioned someone and got an answer she didn’t like.”

Inside the Jury Room

The jurors spent Monday, February 23, going over the evidence, “trying to focus on the facts, not what we thought,” recalls the forewoman. No vote was taken.

Tuesday morning, they took up more reviews of the evidence. By now, according to the jury forewoman, it seemed clear that most jurors thought the plaintiff should win. They voted in the middle of the day, she says, and it was 11-1 that Johnson & Johnson had failed to warn the Pledgers, and the same 11-1 that the failure to warn had caused Austin’s gynecomastia. The juror in the minority argued that the doctor was at fault for prescribing an off-label drug, the forewoman recalls.

That afternoon, they debated how much Johnson & Johnson should pay Austin’s family. Some wanted to award as much as $5 million; others favored a far lower sum, even below a half million dollars. Soon, they focused on what they thought would be Austin’s 50-year life expectancy and began to calculate what he should be paid per year. Dividing a hypothetical total into 50 parts seemed to make everyone more comfortable with a relatively high award.

By Wednesday morning, some of the jurors urged the others to consider that the lawyers, as the forewoman puts it, “were likely to get about a third of the money, and we needed to take that into consideration. … We spent a lot of time trying to calculate that.”

Just before lunchtime, they arrived at a figure: $2.5 million, which worked out to about $33,000 a year after the expected 33 percent in lawyers’ fees. The jurors sent word that they had reached a decision.

The two sides quickly assembled in court in front of Judge Djerassi to hear the forewoman read the verdict.

“It was more money than I could comprehend,” says Benita Pledger.

Sullivan began preparing her appeal, based on multiple decisions the judge had made, including having allowed Kline to bring in the plastic surgeon after the endocrinologist had been scared away on the eve of his testimony. Kline, also appealed, chiefly on the grounds that the decision by an earlier judge that punitive damages could not be granted was wrong.

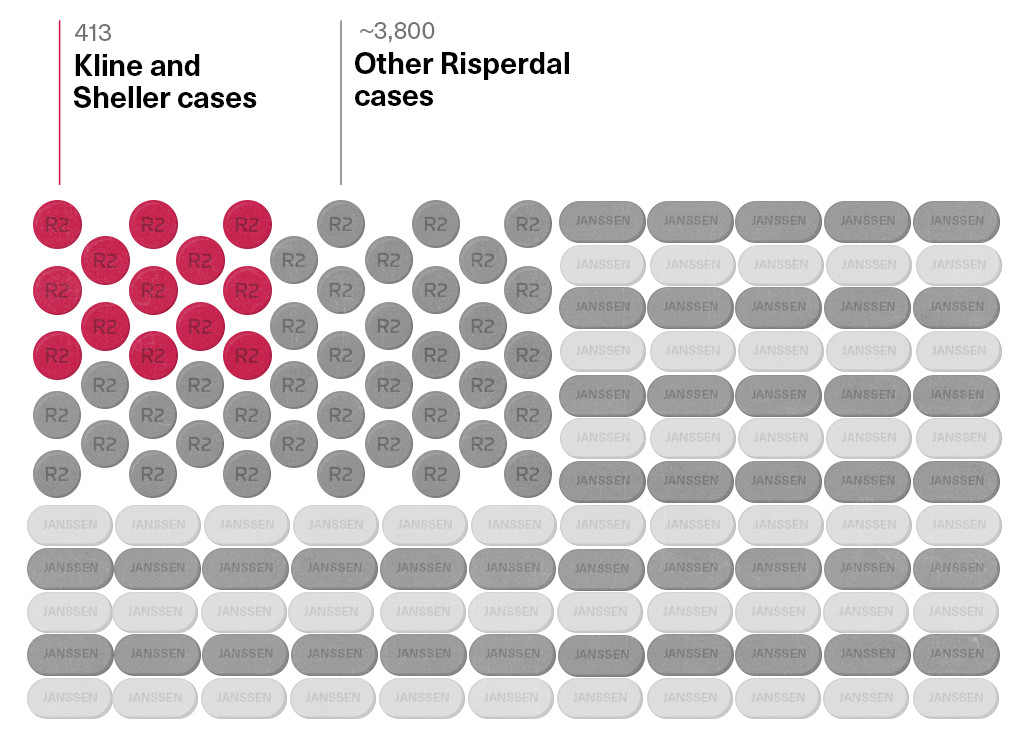

If those appeals are not cut short by a settlement of the case—probably as part of a deal involving all of Sheller’s and Kline’s pending cases, which now number 413—Benita and Phillip Pledger are unlikely to see any money for years.

In June, I spent two hours with them at their kitchen table, while Austin surfed on his tablet. I have been writing about trials for more than 35 years. If the Pledgers were faking it when they seemed unexcited about the money they stood to get, they fooled me. Austin’s mother seemed more eager to talk about the fact that now that her son is older, “his breasts are drooping down to his stomach, like an old lady’s, so they aren’t as visible under his shirt.”

In July, the Pledgers did get one dividend from the trial. For Austin’s 21st birthday Tom Kline bought him and his mother tickets to Los Angeles and arranged for them to visit the set of “Wheel of Fortune.”

Moving On

Following the verdict, the two sides immediately began preparing for the next of the Sheller/Kline cases. Diane Sullivan was replaced by a lawyer from another New York firm.

When that trial began in March, the same witnesses said mostly the same things, although it was difficult to tell why Johnson & Johnson put Caers on the stand again; he seemed to fare even worse on cross-examination this time around. Also, the judge in this case allowed Kline to introduce more evidence of Johnson & Johnson’s business plans to market to children. A sales manager was brought in, much to his discomfort, to take Kline through all the documents discussing those plans and describe meetings, including some that he said involved Gorsky, where the off-label targeting of children was mapped out.

However, the plaintiffs’ lawyers were worried about the case, for two reasons.

First, they had no pictures, like the one of Austin Pledger, proving that the plaintiff had not had breasts before taking Risperdal and had grown them while on the drug. All they had was the boy as he now looked, years later. That made causation hard to prove. He could have grown the breasts after he stopped taking the drug, or before he had ever taken it.

Second, there was the boy himself, and his family. They were from Pennsylvania, and like the Pledgers, they were a working-class family. But unlike the Pledgers they were not the types who appealed to a jury. “The boy had killed cats,” is how Sheller summed up the problem.

When this jury came back with its verdict slip, on March 20, its vote was 10-2 that Johnson & Johnson had, indeed, failed to warn.

However, on the second question, the jury ruled 10-2 that Kline had not proved causation.

Reuters called it a “partial victory” for Johnson & Johnson.

Still, it seemed that the company viewed the glass as half empty. On the eve of a third trial, scheduled for May, the company settled with Kline for what Sheller says “was a very generous amount.”

Kline is now in talks to settle all 413 of his and Sheller’s cases. If settlement discussions fail, the next case is scheduled for trial in October.

The company’s latest SEC filing says there are 4,200 Risperdal claims on dockets across the country. Ernie Knewitz, Johnson & Johnson’s vice president for global media relations, says that his company “hopes we can settle all of the cases.”

“As with the government settlement,” he adds, “which we only pled to a few months of off-label selling by some folks to the elderly, we have to put this baggage behind us. There comes a time when you just have to move on. I know Alex [Gorsky] believes that.”

There Are 4,200 Risperdal Cases Left

(And Kline and Sheller Clients Only Represent a Handful)

Moving Up

At Johnson & Johnson, everyone seems to have moved on. And up.

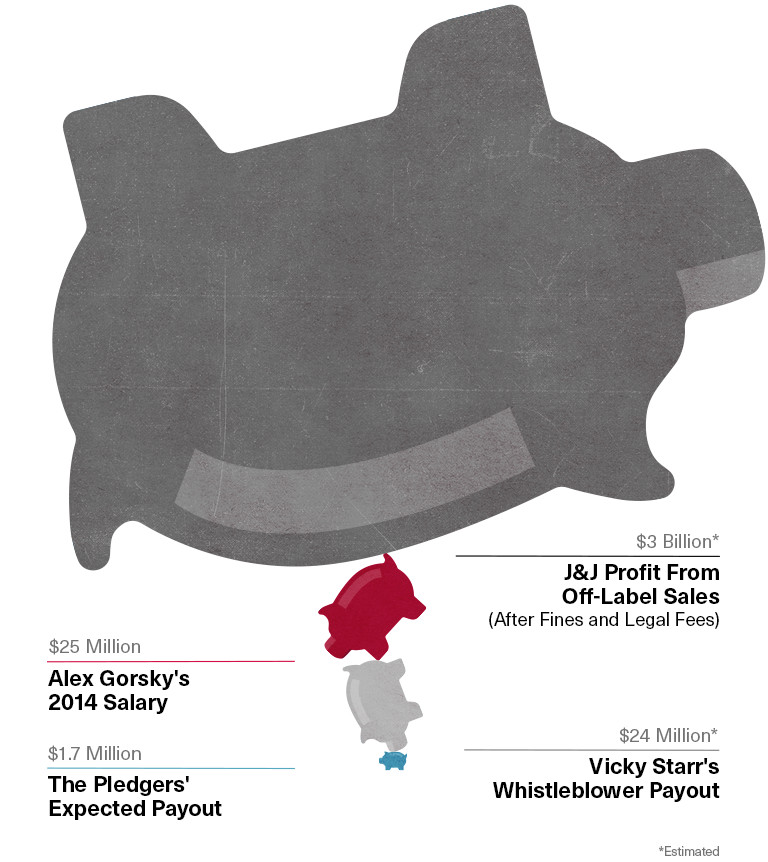

Starting, of course, with Gorsky. The man who is now Johnson & Johnson’s chairman and chief executive got a 48 percent raise, to $25 million, in 2014—the year after the government settlement was completed for $2.2 billion, the components of which included the largest criminal fine and civil damages payment ever stemming from the illegal marketing of one drug.

Gahan Pandina, who was the executive who orchestrated the agreement with Biederman and led the Risperdal roll-out in North America, is now the senior director and venture leader at Janssen R&D.

Ramy Mahmoud, who put together a children and adolescents business plan in 2001, earned a series of promotions at the company before leaving to become president and chief operating officer of a healthcare startup. Its website notes that “Ramy participated in the development, launch and/or commercialization of dozens of pharmaceutical and medical device products spanning multiple therapeutic categories, including blockbusters such as RISPERDAL®.”

Carin Binder, the Janssen executive whom Kline called the “MBA lady” and who wrote the email about the “nauseating amount” of side effects data, became the medical affairs director of Johnson & Johnson before retiring last year.

And Ivo Caers, as we know from his testimony, now runs most of Janssen’s clinical development and studies around the world.

Johnson & Johnson has never come forward with any information that any of its employees was disciplined or fired for illegally promoting Risperdal.

As for the bottom line, Risperdal sales from 1994 through 2008 (when it went off-patent) have totaled approximately $30 billion, including approximately $20 billion in the U.S.

Expenses in the U.S., including all manufacturing and sales and promotion costs, probably amounted to $2 billion based on the business plans and budgets I have seen. That would yield a profit of $18 billion.

Assume half of those profits, or $9 billion, were derived from off-label sales to children and the elderly. Suppose that even $3 billion ends up being spent on all of the remaining litigation (which is my highest-end estimate). With about $3 billion already paid out in verdicts, settlements and legal fees, that would mean J&J will have spent $6 billion to clean up after all of the alleged illegal conduct. The company will still have cleared $3 billion from its off-label sales—despite getting caught.

In other words, the worst possible outcome for J&J—getting caught red-handed and being buried in lawsuits that end up with terrible verdicts or settlements—will still have been highly profitable. (J&J may also have had as much as $300 to $400 million in Risperdal research and development costs, but that money was spent before the first pill was sold and would have been more than recouped from permitted, on-label sales.)

All in all, in terms of the company’s fortunes and the career trajectories of the people responsible for its conduct, it is hard to argue that the system produced much of a deterrent when it comes to illegally promoting its powerful products. It is equally hard not to wonder, considering the totality of the Johnson & Johnson Risperdal story, how much we can count on the integrity of a dominant industry whose most admired company admitted so little, promoted so many of those responsible and continues to thrive so mightily.

The whistleblowers did well, too. Then again, Alex Gorsky’s $25 million 2014 paycheck was about the same as Vicki Starr’s likely reward for 10 years of trying to blow the whistle on him and his colleagues.

The Final Tallies

Certainly the trial lawyers have cashed in. Sheller has gotten a piece—maybe 5 percent, after all the referrals and costs are factored in—of some $5 billion in drug company suits and settlements from four major drug companies. And that doesn’t count the Risperdal personal injury settlements about to come.

Which is appalling until one realizes that if he hadn’t encouraged, maybe even ambulance-chased, the whistleblowers, and if he and his fellow plaintiffs lawyers—including what Diane Sullivan might call the “1-800 crowd”—hadn’t trudged through millions of documents, the companies’ misconduct would have gone unchecked and their victims uncompensated.

The government didn’t do that work.

Not a single qui tam case could have happened—none of those elite assistant U.S. attorneys would have had anything to add to their resumes—without the private plaintiffs lawyers gathering all of the initial evidence.

The FDA could have pulled the same data Johnson & Johnson regularly bought, and seen that Risperdal prescriptions were being written disproportionately by doctors who specialized in treating children and the elderly. But if someone there did, no one acted on it until the whistleblowers came forward.

Johnson & Johnson’s conduct—and that of at least eight other of the 10 largest drug companies that have been caught and are forced to operate under Corporate Integrity Agreements—may have been cured, for now, when it comes to off-label selling. But investigations continue into new avenues of possible misconduct, such as whether the companies, including Johnson & Johnson, are illegally inflating what they say are their average wholesale prices so that they can make more money off of Medicare. (Scan J&J’s latest SEC filing for a précis of these latest brushes with the law).

Beyond that, there’s the larger question of whether the honor system works to ensure that companies with Johnson & Johnson’s Risperdal record, run by the same people who created that record, tell the FDA everything, good and bad, about all of their clinical studies. Every day we read another headline about billion-dollar M&A deals involving drug companies boasting potential new blockbusters whose tests so far look great. Can we know that for sure?

Every time Sheller thinks of the current Risperdal label, with its still-declared rate of 2.3 percent for gynecomastia, he thinks he knows the answer. He is now litigating an FDA “citizens petition” he filed on his own behalf, demanding that the agency withdraw its approval of Risperdal (and its now-prevalent generics) for sale to children. He at least wants the FDA to issue a black box warning about gynecomastia and change the label to reflect a percentage of risk that is higher than what he argues is the fictitious 2.3 percent now on the label. After sitting on it for more than two years, the FDA denied Sheller’s petition, defending its decision about the label and denying that the drug poses the dangers Sheller claims. A federal judge then upheld the FDA’s decision, ruling that Sheller had no standing to bring the petition. Sheller is appealing.

Meantime, Johnson & Johnson spokespeople point to the FDA’s rebuff of Sheller’s charge that the agency unduly acquiesced to J&J as vindication.

There’s no money in this petition battle for Sheller. “I’m just so angry about it,” he says. “It makes me crazy.”

If anything, the way the courts seem likely to handle these issues in the near future could make him crazier. The recent push from the bench, emanating from the Supreme Court, to expand the First Amendment rights of corporations could upend the core principle that a regulatory agency like the FDA can stop drug companies from spending whatever it takes to put their spin on what their products can be used for. That would not only allow promotion for off-label uses; it could ultimately threaten strict government control of the label itself. The country’s most deep-pocketed industry, which markets the world’s most important but potentially most dangerous products, would have finally been given the “sky’s the limit” freedom Senator Kefauver feared in the wake of the Thalidomide tragedy more than 50 years ago.

Some may read the saga of Johnson & Johnson and Risperdal as a story of a company getting off easy—with fines, verdicts and settlements not coming close to erasing the profit from the company’s illegal conduct, and with no one held personally responsible. But despite the company’s guilty plea, nobody in the boardroom and executive suites at Johnson & Johnson seems to think Gorsky or anyone else did anything wrong when they deployed those ghostwritten “scholarly” articles, those “Bridge to Dementia” brochures or those Risperdal Legos to encourage doctors to use this powerful antipsychotic to treat restless nursing home patients or children with behavior disorders. Whatever the small print on a label said or didn’t say about who should get the drug or about strokes, breasts or other side effects should not have been used to punish their passion for getting their drug to as many patients as possible.

Unless Risperdal becomes a cautionary tale, judges seem on their way to ratifying the view from the Johnson & Johnson boardroom.