The Good Soldier,

The Good Mother,

The Faded Star

Stepping Over Toys … and Onto the Stand

Even one of the Johnson & Johnson’s own employees hurt the cause when he was called as a witness for the other side.

After the fighting over the Alabama doctor and his substitute, Kline questioned as a so-called hostile witness Jason Gilbreath, who had worked for Johnson & Johnson in the South for what he said was “15-plus years.” Gilbreath was the salesman who, according to records Kline’s side had subpoenaed, had called on Austin Pledger’s doctor 21 times over two years and dropped off samples equivalent to more than 16,000 children’s doses.

Gilbreath seemed to be the model of the solid citizen R.W. Johnson had had in mind as he built his iconic company and resolved to make it a place where the working man could earn an honorable, secure living. He had gone to work for J&J after getting a degree in avian and poultry science. He and his wife, whom he had married just after high school, still maintained a farm in Alabama, he told Kline and the jury.

Gilbreath began by describing his duties: “to talk about our products to physicians where they are appropriate to use.”

After testifying that he had met with three Johnson & Johnson lawyers to prepare for his testimony, Gilbreath ended up using a favorite word of defense attorneys—“appropriate”—13 more times as he soldiered through a barrage of questioning.

Over two days on the witness stand, Gilbreath claimed that he had no way of knowing for sure that Austin’s doctor—whose Birmingham office plaque said “Pediatric Neurologist”—treated only children (except perhaps for children who had grown into adults and might have remained in his care).

He didn’t “recall” noticing the children’s furniture or decorations in the doctor’s waiting room.

He didn’t know “for sure” that the reduced doses that his company, according to its own internal documents, had packaged for children—and which were the sample packages he gave to Austin’s doctor—were meant for children.

Kline asked Gilbreath if he had ever told Austin’s doctor, “‘Sir, I can’t drop you off children’s samples. That would be promoting.’”

“No, I could not describe where they can or cannot use their samples,” Gilbreath answered. “Once it’s in their custody it’s their discretion where they use them.”

Gilbreath testified that on every occasion he had begun his discussions with Austin’s doctor by asking him to confirm that he treated adults, because, he said, “I know that Risperdal was being used in children, but bear in mind, we were under strict guidance not to promote outside the approved FDA label, and that’s why I had the discussion that I did.”

The only presentations he would give to this doctor or any other, Gilbreath maintained, were about how the drug worked on adult schizophrenia, “because it would be within the scope of the FDA-approved label.”

“I felt bad for the guy they put on who had the farm,” recalls the jury forewoman. “He was just doing his job, saying what he was told to say. … How could he not know the doctor was a pediatrician if he sees toys and kids’ stuff all around his office?”

‘It Was Like There Was Something I Should Be Ashamed of’

Benita Pledger took the stand on February 6, not long after Alex Gorsky was given the Joseph Wharton Leadership Award by the Wharton School’s New York alumni society.

Kline walked Austin’s mother through the story of how, despite his illness, her son—whom she described as “just such a blessing,” “a loving person”—is now able to navigate his tablet and guess the clues on “Wheel of Fortune” before she can.

Then he had her describe Austin’s self-consciousness about his breasts: “I mean, he can see me with my clothes on. He can see my husband without his shirt on. And he knows. … He just doesn’t have the capacity to ask me why.”

Before she explained how she and her husband had been so concerned about Austin’s medication that she called the company’s hotline to find out about the risks, but had not gotten an answer, Kline asked her what she knew about those risks:

- Kline:And did you ever at any time have any discussion or any thought in your head that my boy is developing actual breast tissue?

- Pledger:No. I thought it was the weight gain, and I thought that as long as I kept trying to help him with his weight and exercise, that’s all I could do. I would just have to fight the weight as much as possible. I did not know that his breasts were for any other reason than that.

- Kline:Okay. And did you at any time know that there was any increased risk, of any kind, of your son developing what we in this courtroom have been calling gynecomastia?

- Pledger:No. I knew nothing of that. … I did not know boys could develop breasts or [if] it was a side effect from the medicine at all.

- Kline:If you knew that, would you have allowed your son to be on this drug?”

- Pledger:No.

- Kline:Can you tell that to us absolutely and categorically?

- Pledger:Absolutely not. I—I can—I can’t fight breast growth. I felt like with the weight gain, we could exercise. … You can’t fight something like that. I didn’t even know that was a possibility.

Kline then produced photos of Austin. The first was before he started taking Risperdal. Austin looked fit, arguably even lean. The second was a rare photo taken in 2005 of Austin coming out of the pool without a T-shirt. In the second photo, he looked much heavier; records indicated he had gained over 100 pounds. And his breasts were clearly visible. The third was a photo taken a few days before by Dr. Solomon, the new expert witness. Austin’s breasts were equally apparent.

“The pictures [of Austin] made an impression on all of us,” recalls the forewoman of the jury. “I still remember them.”

“The pictures, I think, made an impression on all of us,” recalls the forewoman of the jury. “I still remember them.”

Diane Sullivan began her cross-examination by getting Benita to agree that her son’s autism was a serious disability and that she had turned to Risperdal because “of the challenges you and your family faced.”

After a lunch adjournment, Sullivan asked Benita to describe how the drug had helped control Austin’s tantrums, which she was glad to do. But she was not as sanguine when Sullivan began reading from vivid school reports that described the tantrums and violent episodes Austin had before going on Risperdal.

Next came reports recording Austin’s improvement after starting his prescription. Then, Sullivan picked up another pile of reports describing his tantrums that were written after he had gone off the drug. She read from one after another, often loudly, recalls the jury forewoman.

To Benita, Sullivan’s reading of excerpts from the various reports was the kind of “cherry picking” that the Johnson & Johnson lawyer had accused Kessler of doing when he had focused on the negative clinical data. “All his [school reports] were similar,” she protested to Sullivan. “Whether he was or was not on Risperdal. Every year I was always open and honest and I wanted them to know. They told me things and I told them. I never tried to candy-coat it. It’s hard. He had a hard time.”

Sullivan persisted: “And in 2009 [after he had stopped taking Risperdal] he was no longer welcome in school?”

“I never said that he was not a problem at school,” Benita answered.

“I have said the whole time he had problems. Risperdal did help. Abilify [a rival drug] helped. Geodon helped. But from kindergarten until the time they didn’t want him there anymore, he had a hard time. That is what the problem is. … There was no fix. Risperdal didn’t fix it, Abilify doesn’t fix it, and Geodon doesn’t fix it. And as he gets older, it’s better.”

Sullivan then showed the jury recent pictures of a smiling Austin Pledger. She got his mother to agree that he is “generally a happy kid.”

It was then that, with a closing flourish, Sullivan asked Benita the series of questions about how the first person to tell her about her son’s gynecomastia “wasn’t a doctor, it was a plaintiff’s law firm” through its 1-800 commercial.

“Yeah, it’s really a shame that a lawyer had to tell me about my son’s condition instead of the drug company or a doctor,” Benita Pledger later told me. “Like I’m supposed to be embarrassed about that? No doctor ever examined him with his shirt off. They thought he was just fat. So when she said that, it didn’t make me feel bad. ”

What bothered her more about Sullivan’s cross-examination was, she says, the way “Sullivan raised her voice when she read those school reports, and acted like she had caught me. It was like there was something I should be ashamed of. … Austin’s not some kind of juvenile delinquent. He’s an autistic young man.”

“I thought the mother was quite brave to subject herself to all of this,” recalls the jury forewoman. “I felt bad for her.”

J&J’s Star

Diane Sullivan’s key witness for the Johnson & Johnson defense—her answer to former FDA Commissioner David Kessler—was Lodewijk Ivo Caers, who told the jury he went by the name Ivo. Caers seemed to be Sullivan’s bet that she could convince the jurors that Johnson & Johnson was a proud, meticulous, ethical company. That the Credo was real.

As Sullivan walked Caers through his biography, he explained to the jury that he had been doing research and development at Janssen’s original home base in Beerse, Belgium, for more than 35 years. As a young scientist he had even worked in a laboratory “on the same floor” as his company’s legendary namesake, Paul Janssen, who, he said, had been “the inventor of up to 80, eight-zero, new drugs for different areas of medicine.”

Caers had worked his way up, he testified, until he had been put in charge of many of Janssen’s clinical studies around the world and their release to regulators and through academic articles. From the beginning of Risperdal’s pre-approval clinical studies through its rise to blockbuster status, he had been the man in charge of the drug’s development and preparation for the market.

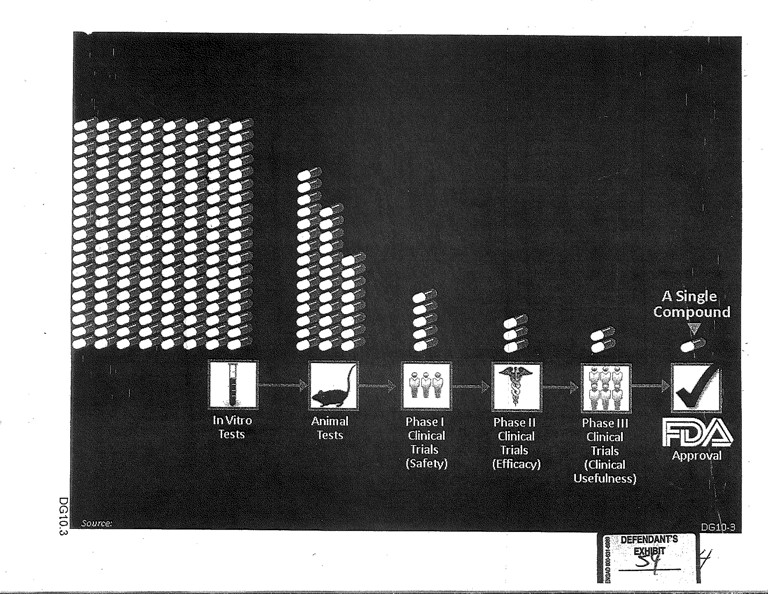

Caers walked the jury through all of the steps involved in getting a drug to patients—from scientists in a lab having a hypothesis about a molecule, to tests on animals, to tests on humans and, finally, to FDA approval following “thousands of pages” of data submissions.

Sullivan then turned to Risperdal specifically. That gave Caers the opportunity to talk about all the studies of side effects in children that his group had reported to the FDA, including data about gynecomastia—and about how, because he had three children and seven grandchildren, he knew how difficult it was to find children to enroll in drug studies.

Then came the crux of Sullivan’s defense.

- Sullivan:And, Dr. Caers, in the adult label from 1993 [the label in use when Austin Pledger took the drug], is there a section that tells doctors about safety for children?

- Caers:The only reference to children in the label of ’93 is a statement that the efficacy and safety of Risperdal in children has not been established.

- Sullivan:Okay. And that was in the adult label from the beginning?

- Caers:That is correct. Well, it’s in the Risperdal label, full stop.

Sullivan then got Caers to say that he had submitted data to the FDA about the raised prolactin levels in patients taking Risperdal.

In other words, the FDA had been told everything and even required Johnson & Johnson to say that efficacy and safety in children had not been “established.” So, how could Johnson & Johnson be at fault? Any doctor reading the label knew, because J&J told them, that there was a risk in giving Risperdal to kids.

Sullivan now moved to have Caers sweep away all of those Kessler allegations. He rattled off the 18 different studies, one by one, that his company had done examining the safety of Risperdal when given to children. Most had been placebo-controlled, meaning half of the participants had been given a sugar pill instead of medication and the results had then been compared. All of those studies, which were designed with the help of “outside expert” doctors, had been reported to the FDA, Caers said, and then reported in medical journals.

Caers and Sullivan devoted particular attention to a report that combined all of these studies and involved 1,885 children taking the medication. It had yielded the finding—included in the 2006 label—that gynecomastia had resulted in 2.3 percent of the cases. Sullivan asked about “some criticism” from Kessler of how the pooling of the studies diluted the reality of a much higher percentage of gynecomastia cases in one of the studies, the so-called INT-41. Caers said, with no explanation, that the pooling had been the FDA’s idea.

Sullivan then took aim at the INT-41 study.

INT-41, Caers explained, was not a placebo-controlled study, meaning everyone was given the drug. In testing efficacy, giving placebos to one group of the subjects is thought to be important because many patients will feel better or even exhibit improvement if they believe they have taken medication. But in studies meant to test a drug for side effects, placebos have far less import. Besides, INT-41 was designed as a long-term study, and as Caers himself had pointed out, it is difficult ethically and practically to ask children to take no medicine when medicine could help them, let alone ask them to do so for a long time.

This was the largest study by far. And it was one of only two out of the 18 that had studied the long-term use of Risperdal, which was crucial. As in the case of Austin Pledger, gynecomastia was only thought to develop after long-term use. Equally important, INT-41 was the only study designed to pay “special attention” to gynecomastia—which, if one believes Benita Pledger’s testimony, can go unnoticed if not looked for.

None of that was lost on Kline who was growing antsy, he recalls, to start his cross-examination.

Sullivan did not ask Caers to respond to Kessler’s assertion that it would have been legal, and indeed was required, for Janssen to have added a warning about gynecomastia in 2000 once it saw the 5.5 percent incidence rate in that INT-41 study. Kessler had testified that the company should have done that and also sent a warning notice to doctors, rather than wait until a new label was approved in 2006, long after the study had been completed.

However, Sullivan did try to refute Kessler by implication by having Caers testify that the FDA had rejected Janssen’s request to put children’s (lower) dosing suggestions on the earlier label. Apparently, she believed jurors would not appreciate the difference, as Kessler had claimed, between warning about a danger to children and adding language to the label explaining how to administer the drug off-label to them.

Finally, Sullivan turned to the Findling article and the addition of the table excluding boys 10 and over after the initial draft was written. Over a long series of questions and answers, Caers brushed off the issue as a simple matter of the company’s outside expert advisors deciding that the new table made for better science.

As for why the table showing the statistically significant relationship between raised prolactin levels after eight weeks of treatment and incidences of gynecomastia had not been included, Caers dismissed that, too. It had just been one of many analyses that routinely get reviewed and discarded as scientific articles are prepared, he said.

And here, verbatim, is how the doctor explained why the original denominator including all the children had survived, despite the elimination of all of those boys aged 10 and over:

“Well, the whole analysis is done on the total population, and it is not because you exclude a couple of adverse events due to puberty, rather than prolactin, that you can remove those subjects from the denominator. That’s clear.”

The jury forewoman did not agree. “I never got the Johnson & Johnson scientist’s explanation of the numerator-denominator percentage thing,” she recalls. “I didn’t know what he meant.”

‘Wow!’

Kline dove into his cross-examination of Caers by taking him through each of those 18 studies he had cited, and that had produced the 2.3 percent gynecomastia rate that was on the label since 2006. He had Caers recite the duration of each study, demonstrating that most, unlike INT-41, were short-term. He wrote Caers’ answers on a whiteboard for the whole courtroom to see. He then got Caers to concede that all but one of the gynecomastia cases had turned up among the children in the smaller subset of long-term studies. That meant that a truly relevant sample—children taking the drug long-term—would have yielded a much higher percentage of cases than the 2.3 percent listed on the current label, let alone the “rare” description on the label when Austin Pledger was given the drug.

Kline then asked Caers about the decision J&J made in preparing the Findling article to eliminate children 10 and over from their conclusions about their data. He noted that none of the studies Caers had just been talking about, and that Caers had been in charge of designing had “used a cut-off age at ten, correct?“

“Correct,” Caers acknowledged.

It went downhill from there. Kline confronted Caers with emails reporting on the meetings of the outside expert doctors and asked him to identify where any of them stated that the outsiders, not Janssen people, had suggested the elimination of the ten and over children. He could not find it.

Finally came the issue of the table that showed a statistically significant relationship between elevated prolactin and gynecomastia after eight weeks of treatment, but that had not been included or mentioned in the Findling article or anywhere else.

When asked about it by Sullivan, Caers had repeatedly referred to the table and its data as a routine “exploratory analysis”—something that may be looked at in the lead-up to a more formal study but that could eventually be excluded as not relevant.

“You’re not supposed to ask a question if you don’t think you know the answer,” Kline says. “And we didn’t know.”

Kline told Caers he had never heard a Johnson & Johnson witness use the term “exploratory analysis” before, and pointed out that in 12 hours of depositions Caers had never used it.

That seemed to suggest a question that Kline and the other lawyers on his team had debated on and off for weeks over whether he should ask: Had Caers failed to submit that analysis to the FDA?

“You’re not supposed to ask a question if you don’t think you know the answer,” Kline says. “And we didn’t know.”

Under federal law, it is a crime for a drug company not to submit “a description and analysis of each controlled clinical study pertinent to a proposed use of the drug.” Similarly, it is a crime to fail to submit “a description and analysis of any other data or information relevant to an evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of the drug product obtained or otherwise received by the applicant from any source, foreign or domestic, including information derived from clinical investigations.”

“I had a feeling about it,” recalls Kline. “And as I heard him talk about it, I just decided to go ahead.”

Actually, Kline is giving himself too much credit. It was Sullivan who cleared the way for Kline to ask the question, at no risk—because she asked it first, indirectly, during her late-afternoon re-direct examination of Caers after Kline’s initial cross-examination was over.

Sullivan: Dr. Caers, can you tell our jury why Table 21 wasn’t given to the FDA?

Caers: Well, because obviously, this is not an analysis that was intended for the FDA because this is an explorative analysis.

Caers then said that the FDA could have found the relevant data that comprised the table among the thousands of pages of data the company had given the agency to review. Of course, the reviewers would have had to have found it, organized it and decided to make their own table from it, which is why the law requires that tables analyzing data that are prepared by the drug company must be submitted.

“[T]he FDA had all those data available in the submission and even in the database and could do similar analysis,” he said.

It was only after Sullivan had that exchange that Kline shot up from his chair for a brief re-cross examination:

- Kline:Sir, table 21 was not given to the FDA?

- Caers:That’s correct.

- Kline:Wow!

- Sullivan:Your honor, I object to the interpretation.

According to an experienced lawyer who was in the courtroom but was not allied with either side, “That moment seemed like a big surprise to the jury—that after all he had said about all the studies Janssen had turned over to the FDA, that he had never turned that one over. … There was a pregnant pause after that.”

The jury forewoman agrees. “I thought that was really important, when he said he had thrown out that study. … What this was really about, was that you can’t keep testing over and over again and then use the results you like and throw out the rest.”

When witnesses finish testifying, the lawyers’ closing arguments in a complicated case like this are especially important. Can they skillfully spin everything that the jurors have heard into a coherent story? Can they deploy the right metaphors or images to get the jurors to remember the points that help them the most? Can their tone get the jurors to trust them?