Under Siege,

Ducking

and

Weaving

‘Vigorously Contesting the Allegations,’ But…

By March 2010, when Johnson & Johnson filed its financial disclosure with the Securities and Exchange Commission covering the events of the year 2009, the world’s leading healthcare company was forced to list a daunting collection of suits and investigations involving Risperdal. Subpoenas seeking testimony of its executives “before a grand jury” had been received from the U.S. attorney’s office in Philadelphia investigating the marketing of the drug. Other subpoenas had been issued for company officials to testify before a grand jury in Boston looking into the Omnicare relationship. Two qui tam suits had been filed in Massachusetts related to that deal, too, and suits seeking damages and fines had been filed by nine different states.

Beyond that, the company reported that “multiple products of Johnson & Johnson subsidiaries are subject to numerous product liability claims and lawsuits.” Two other allegedly faulty J&J products targeted by the plaintiffs lawyers were a device called a transvaginal mesh patch and an artificial hip implant. Suits involving these two products would soon end up competing with Risperdal for claims on the company’s reputation and treasury.

Johnson & Johnson seemed to take the threats in stride. “The Company and its subsidiaries are vigorously contesting the allegations asserted against them,” its SEC filing declared.

But just in case, the amount that Johnson & Johnson had removed from earnings for 2009 and reserved for liabilities was listed as $1.014 billion—or about 6 percent of its $15.755 billion in pretax earnings for the year. Putting that much aside each year over what was perhaps the fifteen-year life of these potential legal battles was not going to cut deeply into the company’s bottom line.

“In the Company’s opinion,” the filing declared, “based on its examination of these matters, its experience to date and discussions with counsel, the ultimate outcome of legal proceedings, net of liabilities already accrued in the Company’s balance sheet, is not expected to have a material adverse effect on the Company’s financial condition.”

Perhaps, but its reputation was another matter. Its best known, family-friendly products were also about to take a turn in the penalty box. And in this case, the alleged misconduct went to the core of Johnson & Johnson’s reputation; it wasn’t about how the company marketed its products, but about the basic care it took in making them.

‘Gram Negative’ Bacteria in Children’s Tylenol and the ‘Phantom Recall’

Beginning in 2009 and extending into 2010, the FDA division that regulates the safety of over-the-counter products conducted inspections of factories at J&J’s McNeil Consumer Healthcare division. The result was a series of lurid reports documenting deficiencies in how the company was producing everything from Tylenol, to Pepcid, to Visine, to Rolaids, to children’s Motrin, to Benadryl, to PediaCare cough syrup for babies.

Many of the inspectors focused on what an April 2010 report described as “known contamination of gram negative organisms.” These are bacteria that can cause a variety of infections, such as E. coli and even cholera. The inspectors found routine contamination that included bacteria and metal particles in products such as children’s Tylenol, as well as haphazard controls on the precise mixes of the chemicals that were supposed to be contained in the products, causing some to be too strong and others to be too weak. The overall picture brought to mind production facilities in a developing country rather than the pristine factories of R.W. Johnson’s idyllic American enterprise.

Then-FDA deputy commissioner Joshua Sharfstein would tell a congressional committee in September 2010 that “one common concern the Agency has found across these facilities is the failure to investigate and correct product problems in a prompt and thorough manner.”

“In February of this year,” Sharfstein continued, “FDA called an extraordinary meeting with senior executives of Johnson & Johnson. … FDA confronted these executives about whether [its] corporate culture supported a robust quality system to ensure the purity, potency and safety of its products.”

Among the cultural issues Sharfstein raised was what he called J&J’s “phantom recall” of Motrin tablets in the spring of 2009. That was when, as he explained, “the company had paid a contractor to go into retail stores across the country to purchase all available product while acting like a regular customer, and not disclosing whether it was a recall.”

As a result of these FDA inspections, J&J was ordered to do a series of real recalls of a dozen of its consumer products. The agency also forced the company to shut down a factory in Pennsylvania until repairs could be made, sanitation safeguards could be implemented and entire processes retooled.

For students of corporate management, the phantom recall should have been especially emblematic of how a company could change.

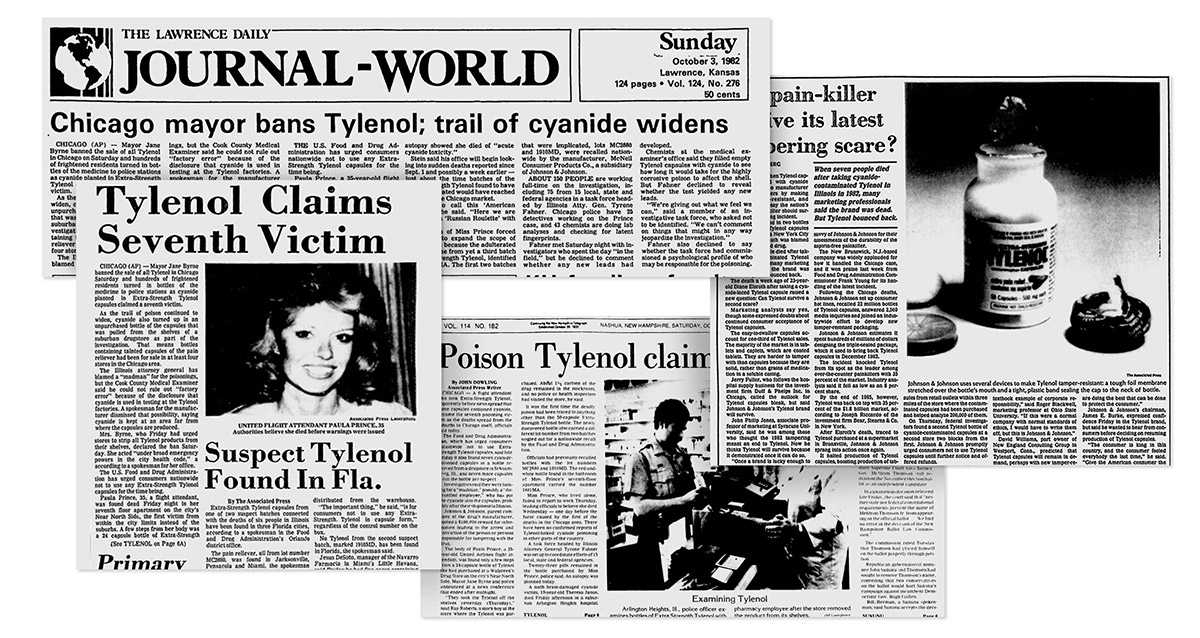

Johnson & Johnson had burnished its reputation for honest dealing with customers and regulators in 1982, when it was discovered that Tylenol capsules had been poisoned with cyanide. Seven people died. Scary headlines about the dangerous product dominated the news.

From the moment the crisis began to unfold, James Burke, J&J’s chairman and chief executive, took a series of extraordinary steps that he said he believed the company’s Credo dictated. He immediately recalled all Tylenol products. He was readily accessible to the press. He went on television and issued press releases telling people not to buy any Tylenol that might still be on the shelves. He apologized. And he organized an all-hands-on-deck drive to repackage Tylenol and all similar Johnson & Johnson products in sealed containers.

It took a few years, but a brand thought to have been irretrievably damaged resumed its place as a consumer favorite.

In the years since, Burke’s blunt, upfront handling of the Tylenol sabotage has been celebrated in management schools as the ultimate model of corporate crisis management.

The Feds Close In

While Johnson & Johnson was wrestling with its un-Burke-like handling of the quality breakdowns in its consumer division, the government accelerated its pressure on the Risperdal front.

The news, on November 3, 2009, circulated not only in the conventional media, but also on the websites and in social media channels of lawyers seeking more Risperdal whistleblowers and personal injury clients.

“The nation’s largest nursing home pharmacy, Omnicare Inc. of Covington, Kentucky, will pay $98 million,” Assistant Attorney General Tony West announced, to settle charges that it “solicited and received kickbacks from a pharmaceutical manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson (J&J), in exchange for agreeing to recommend that physicians prescribe Risperdal, a J&J antipsychotic drug, to nursing home patients.

“J&J’s kickbacks to Omnicare took multiple forms,” West’s press release continued, “including rebates that were conditioned on Omnicare engaging in an ‘Active Intervention Program’ for Risperdal and payments disguised as data purchase fees, educational grants, and fees to attend Omnicare meetings.”

Nothing was announced about the consequences for the payer of the “kickbacks”—Johnson & Johnson. West was silent about that, because J&J, unlike Omnicare, had not made a deal.

West, along with acting Boston U.S. Attorney Michael Loucks, had been making a name for himself in dealing tough with drug companies in a series of settlements. But J&J was in no mood to accept the bargain they had offered—yet.

“We wanted to resolve all the Risperdal issues at once—the one in Boston and the grand jury investigation in Philly,” recalls one J&J lawyer, referring to the qui tam suits Sheller had initiated in Philadelphia. “And they were still being coy about what they had or what they wanted from us. So we said we’d fight this one until we could deal with everything.”

Johnson & Johnson did not dodge headlines for long. On January 25, 2010, Loucks, joining a qui tam suit filed years earlier by two Omnicare whistleblowers, sued J&J alleging the same illegal dealings. “Johnson & Johnson accused of drug kickbacks,” The New York Times declared.

Immediately, Loucks applied more pressure. Among other moves, he began what would be a two-year fight to force J&J to make Alex Gorsky—now thought to be in the running to become the next Johnson & Johnson CEO—available for a deposition in the case.

The company still wasn’t ready to yield, according to the lawyer who explained the strategy of holding out on settling the Omnicare charges. “The top company people, Gorsky included and especially [then-CEO William] Weldon, were saying they were ready to fight it all if they couldn’t resolve it satisfactorily,” this lawyer recalls. “They thought this off-label stuff was bullshit.”

The company’s view in that regard would be reflected in a memorandum sent to me by Vice President for Media Relations Ernie Knewitz as I was preparing this article. Knewitz quotes from various government hearings and documents that, in the company’s view, acknowledge—indeed sanction—off-label sales of Risperdal and confirm that the drug was effective. The memorandum can be found here.

‘We Thought We Had Them’

In January 2010, Kurtis Berry decided to join what by now looked like a lucrative Johnson & Johnson qui tam party being organized by Sheller and his team. Berry was a big catch. He had been a regional sales manager for Janssen in the Northwest and was easily able to tie J&J senior executives to information from Starr and from two other sales rep “relators” who had joined the group.

“When Berry came in, the government stopped beating around the bush,” Sheller recalls. “They told us point-blank that they were in, and went into overdrive. It was a turning point. Now, we thought we had them.”

At some point a year or two into what was now her nearly seven years as a secret whistleblower, Vicki Starr and her husband had mentioned to their accountant that she might be paid a substantial amount of money, well beyond their current earnings, for a project she was working on. They asked if there was any special planning they might need to do in case that happened.

There was one thing they might think about, the accountant told them: Oregon taxed personal income, but Washington, just over the border from where they lived, did not. If they really thought they might get a windfall, they could consider moving to Washington. They would have to establish residency there for at least six months in the calendar year in which the income was going to be received.

As a result, from time to time, and almost as an excuse to get into a conversation about how things were going, Starr, having told her lawyers about the accountant’s advice, would ask them if she and her husband should be thinking about moving. Through 2010 their answer remained the same: no reason yet to go house hunting.

However, a Texas lawyer’s revelation would soon help make that move over the border more likely.

A Texas Lawyer’s “A-ha” Moment

Good trial lawyers know they have to spin a story that jurors will understand. It has to be something that puts all the pieces together and explains (if you’re a plaintiffs lawyer or a prosecutor) why the bad guy did something bad, or (if you’re a defense lawyer) why this good guy is being accused of doing something he didn’t do. Jurors need a reason to believe.

By 2011, Tom Melsheimer, who was beginning his 25th year practicing law, was already a celebrated storyteller. He had become famous in Texas legal circles in 1991 when, as a federal prosecutor, he won convictions in the locally famous “I-30 scandal.” It involved a flamboyant real estate developer and 66 other defendants who were convicted in a scheme that defrauded the government of $1 billion. Melsheimer led a trial team that turned a byzantine set of corporate transactions and interlocking corporate entities into a caper that the jurors could understand.

As 2011 began, Melsheimer was also working on a case for the Dallas Mavericks basketball team, which was being sued by minority owner Ross Perot Jr. for mismanagement. A brief he would file in June for summary judgment in that case generated publicity and praise far beyond the legal world for how he told the story. A local newspaper called it “The Greatest Legal Brief in the History of Jurisprudence,” and the sports website Deadspin dubbed it “The Ultimate F—You Legal Brief.”

Melsheimer titled the brief, “World Champion Dallas Mavericks and Radical Mavericks Management’s Motion for Summary Judgment.” He then used an over-the-top (for a legal brief) visual aid—a picture of the Mavericks celebrating their recent world championship—to drive home his simple story: that it was beyond the pale to claim that this championship team was the victim of mismanagement. Melsheimer would go on to win the motion—and get more accolades two years later when he successfully defended Mavericks owner Mark Cuban in a bitterly-fought trial against the SEC over insider trading charges.

Now, as he contemplated the documents he and the Texas attorney general’s staff had subpoenaed from Johnson & Johnson for the qui tam suit brought to them by Allen Jones, the former Pennsylvania auditor, Melsheimer was struggling to figure out what story he could tell this time.

Yes, Jones had brought him persuasive evidence, now backed by the internal Johnson & Johnson documents Melsheimer had reviewed, that the company had improperly set up that TMAP algorithm. The allegedly phony TMAP algorithm had been used to replace Haldol with Risperdal, because Haldol was now off patent and, therefore, far cheaper. Yet studies never proved that Risperdal was more effective than Haldol, so the Texas taxpayers were getting cheated by the upsell.

But companies always try to sell as much of their most expensive product as they can, Melsheimer recalls thinking. It’s a plausible story, but not terribly compelling or surprising. And it risks getting bogged down in studies comparing the two drugs. Experts could no doubt be found to testify on both sides.

It was on March 21, 2011, that Melsheimer realized there was a bigger, better story. He was meeting in Dallas with Joseph Glenmullen, the Harvard psychiatrist and outspoken antipsychotic skeptic whom Stephen Sheller had befriended and retained as an expert advisor. Sheller had referred Glenmullen to Melsheimer.

“Glenmullen began to talk about what the drug was supposed to be used for – psychotic disorders, meaning schizophrenia and other departures from reality,” Melsheimer recalls, “and what it was really being used for in Texas under TMAP, which was any kind of behavior disorder, including in kids. And then he casually said, as if I knew it, that it was all about the population numbers.”

Melsheimer asked the doctor what he meant. “He walked me through,” Melsheimer says, “how the market for which Risperdal had been approved—psychotic disorders like schizophrenia—affected maybe 1 percent of the population. But behavior disorders were maybe 3, 4 or 5 percent.”

At that point, Melsheimer remembered something he had seen in one of those internal Johnson & Johnson documents: the original Risperdal marketing plan for the 1994 rollout. Suddenly this statement in the plan, under “Conclusions” on page 4, took on new meaning: “The anticipated growth of the antipsychotic market” —the relatively small population of people with the most severe disorders—“does not create enough room for the Risperdal sales forecast.”

“That was my ‘A-ha’ moment,” Melsheimer told me. “This wasn’t just about selling a more expensive product. It was about using TMAP and off-label promotion to radically expand the market, which is exactly what their own marketing plan said they had to do to hit their projections.

“I knew what my story was going to be.”

The Feds Team Up With The Whistleblowers

By the time Johnson & Johnson filed its report with the SEC for the first fiscal quarter of 2011, its disclosure of Risperdal’s assorted legal troubles had grown to three pages of small type describing multiple civil and criminal investigations.

Buried in there was this scoop: The government had finally jumped into Sheller’s qui tam cases brought by Vicki Starr and the others. “The Government has notified [Johnson & Johnson] that there are also pending qui tam actions alleging off-label promotion of RISPERDAL ®,” it read. “The Government informed [Johnson & Johnson] that it will intervene in these qui tam actions and file a superseding complaint.”

That acknowledgement was followed by a recitation of all the other cases now targeting Risperdal. Suits by a parade of attorneys general were listed, describing in repetitive language the allegations in each.

One such case, in South Carolina, was already on its way to resulting in a judge penalizing the company $327 million after a jury found J&J liable for improperly marketing the drug and concealing its diabetes risks, particularly to the elderly. In levying the penalty, the judge said the company’s off-label marketing campaign had demonstrated a “profit at all costs” mentality. (The verdict would ultimately be reduced by the state Supreme Court to $137 million.)

Following the list of Risperdal troubles in the SEC filing was a new entry—J&J’s McNeil Consumer Healthcare division. Here, the disclosures were all the new investigations and suits that had been launched as a result of the FDA inspections and the “phantom” recall.

Still, the company reported, as it had before, that “the ultimate resolution of these matters is not expected to have a material adverse effect on the Company’s financial position.”

Jonathan Rockoff and Joann Lublin of the Wall Street Journal caught wind of the SEC filing and added their own reporting the next morning. Noting that in its disclosure Johnson & Johnson “said it set aside an unspecified amount for a potential settlement, and said it would ‘likely’ face civil and criminal litigation if it didn’t settle,” the Journal reported that “federal prosecutors are seeking roughly $1 billion to resolve the charges.”

Shutting out Sheller

When Vicki Starr called Stephen Sheller to ask about the Journal’s billion-dollar figure, he still told her nothing was certain and that there was still a long way to go.

In fact, her lawyers didn’t know much more than Starr did. According to Sheller, “once the feds got in, we were shut out.”

Sheller was spending his time pursuing cases for plaintiffs who claimed to have been injured by taking Risperdal. By now he had spread the word among trial lawyers that he had great information about Risperdal and gynecomastia. He had put deals in place to get referrals from across the country, and they were coming in by the dozens.

The referring lawyers would get a piece of his piece of any settlements or verdicts. At least one was buying TV time across the country to use a tested, if tacky, method of gathering clients en masse.

‘Did Your Son Take Risperdal and Grow Breasts? Call 1-800…’

One night in October 2011, Benita Pledger was watching television with her now 17-year-old son Austin in their two-bedroom, single-story home in Thorsby, Alabama. They were sunk into a soft couch, just off the kitchen and outside Austin’s bedroom. The flat screen, which loomed like a Jumbotron in the living room, was showing a syndicated rerun.

Benita remembers that it was close to Austin’s 8:20 bedtime. She also remembers that it was just before Halloween because, as Austin stared at the television, she was thinking about having a treasure hunt for him that year instead of taking him trick or treating.

As much as Austin loved candy, Benita and her husband, Phillip, had tried mightily to keep their son away from sweets. Austin’s weight had become a near-obsession for his doting mother. He had grown so obese that four years before, in 2007, she had asked the doctor to take him off Risperdal. He was now on a different anti-psychotic. His weight was down, she recalls, but only slightly. At least he had stopped getting fatter.

As had been the case when Austin was taking Risperdal, the head-bangings or attacks on teachers or the other students in his special education classes—which happened most often when there was some change in his routine, or when he was otherwise confused—had been less frequent than before he had been given any drugs. But they still happened.

The Pledgers made it a point to be with Austin. They played along or cheered him on as he demonstrated his astounding capacity to recite book passages from memory, and laughed with him as he watched YouTube re-runs of Nickelodeon shows on the tablet he seemed always to have in his lap.

“When I was wearing my nightgown at night he looked at me and you could tell he thought he looked like me up there,” says Benita Pledger. “Not like the other boys he knew.”

They took shifts, which was made easier by the fact that Phillip could walk across the lawn to and from his car repair shop.

But other than Austin’s sudden tantrums and his continuing inability to read social cues and engage in any kind of social conversation, the major shadow in the otherwise happy family life that they had established remained Austin’s weight—and the unusual way it made him look and feel.

“It seemed that so much of it was up top, in his chest,” Benita recalls. “He knew it wasn’t right. … When I was wearing my nightgown at night he looked at me and you could tell he thought he looked like me up there. Not like the other boys he knew.”

While watching television with Austin just after 8:00 on that Wednesday night, Benita Pledger realized that the fat might not just be fat.

“Suddenly a commercial comes on,” she recalls, “You know one of those 1-800 things, and the announcer says something like, ‘Did your son take Risperdal and develop breasts? If so, it’s a condition called’ and I guess he said gynecomastia, though I didn’t know what that meant at the time. And then there was the 800 number you could call to talk to a lawyer about suing the drug company.”

She says she was shaking as she grabbed for a pen to write down the phone number. “I did all I could do to pull myself together to put Austin”—who had not seemed to notice the commercial—“to bed.”

Then she sat at the kitchen table just behind the flat screen, and stared at the phone number. Phillip was off practicing with a band he played in, and she was wondering if she should talk to him first. She knew that, like her, he was not the kind of person who thought about suing people. Bad luck was bad luck, or maybe God’s will. It was not something to go to court about.

But then she got angry. Maybe this wasn’t something that had just happened to them and their son. Maybe it was someone’s fault. The company’s fault.

She dialed the 1-800 number “It was a law firm in Texas,” she says. “The young lady asked me a few questions, then asked if I had any way to email or text her a picture of Austin.”

Austin was not yet asleep, so his mother stepped into his bedroom and said, “Baby, you know how you’ve been dieting and trying to lose weight? Can I take a picture of your muscles?”

“So he took off his shirt and flexed. He was so proud. Then I asked him to turn so I could take another picture from the side.”

The woman from Texas called back almost immediately to tell Benita Pledger that it looked like she had a good case. They would be sending her some papers to sign.

When Phillip came home, his wife nervously told him about the ad she had seen.

“Benita thought I’d be angry,” he recalls. “I wasn’t angry at all with her. I was angry with the company.”

The Texas number Benita had called belonged to the Thomas J. Henry law firm, which is based in Corpus Christi. Run by the brothers Thomas and Michael Henry, the firm seems to derive much of its income from investing in 1-800 ads seeking clients injured in a variety of mishaps, then referring them to lawyers who are actually deep into litigating those cases. They get a share of anything those lawyers win from any settlements or verdicts as their referral fee.

“They have quite a TV and telephone operation,” says Stephen Sheller. “They send us clients and get maybe 5 or 10 percent of what we get”—which is typically a quarter to a third of the client’s payout, but can be as much as 40 percent in some states.

“They sign up hundreds or thousands of people with those TV ads,” Sheller adds, “It’s a good business.” (On the day Sheller spoke with me last winter from his office in Philadelphia, he noted, with a chuckle, that the night before he had seen the Corpus Christi firm’s ads on local television seeking clients who had been injured or whose family members had been killed in an Amtrak accident in Philadelphia a few nights before. Henry firm spokeswoman Susan Harr declined to comment on the percent of cases the firm gets from television ads, or how many clients it had signed up stemming from the Philadelphia train accident.)

Of course, what the Henry firm does is only a good business if the lawyers have strong enough cases to win big verdicts or negotiate generous settlements. And when it came to Risperdal, that part of the equation had yet to be tested.

‘There’s Not Enough Schizophrenic People’

“I’m Tom Melsheimer. During my time with you today, I want to review what I expect the evidence will show in this trial. The gist of it is this: Janssen, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, engaged in a wide-ranging fraudulent scheme to market and sell Risperdal, a drug that was no better and in some ways worse than older less expensive antipsychotic medications. …”

So began Tom Melsheimer’s opening statement on January 10, 2012, to a jury in Austin that would decide the case that former Pennsylvania auditor-turned-whistleblower Allen Jones had brought to Melsheimer.

Finally, Johnson & Johnson was facing off with accusers in court.

A lawyer from the Texas attorney general’s office had briefly preceded Melsheimer with a dry overview of the allegations. Her office was now partnering with Melsheimer in this state qui tam case, seeking to recover hundreds of millions of dollars of the state’s alleged overpayments stemming from the J&J-generated TMAP algorithm scheme that had dispensed so many Risperdal prescriptions in state mental institutions and to state Medicaid recipients.

Melsheimer covered all the elements that he was now convinced made for a compelling story: Johnson & Johnson had made false claims about the drug being better than Haldol. The company had failed to warn about the risk of stroke and other dangers to the elderly. And the TMAP guidelines dictated that Risperdal be used for state-paid patients, instead of the cheaper older drugs, only because TMAP was “a fraudulent scheme.”

Melsheimer promised to back that up by producing evidence—found in still more discovery documents—that the three doctors who drafted the TMAP algorithm guidelines set up their own company and that, “Janssen paid that company $600,000 to go out all throughout the country and promote these guidelines, seemingly as an independent third party.”

Then came Melsheimer’s roll out of his “A-ha” moment, which he was convinced would make the whole story something the jury could believe in: All of the TMAP scheming had happened, he charged, not simply because some sales manager wanted to squeeze out more revenue wherever he or she could, but because the business plan from headquarters demanded that the market for the drug had to be extended well beyond its approved label usage.

“This is an interesting phrase,” he began, reading from what he explained was the company’s 1994 marketing plan. “The anticipated growth of the antipsychotic market does not create enough room for the Risperdal sales forecast. … In other words, there’s not enough schizophrenic people to sell Risperdal to get our sales forecast hit. … That meant that they were going to have to establish it as a broad-use product. Again, this is in the fall of 1994. And what does that mean? A critical success factor for them in that market expansion—they identified this back in 1994—was children. Children. Now, think about this. The success they’re talking about here was not a medical breakthrough. It was a financial breakthrough. Janssen knew that if it could sell—push its drug on children, it could help make the drug financially successful.”

Listen to ‘the Real Doctors Who Just Treat Folks’

Stephen McConnico, a veteran trial lawyer and partner at an Austin corporate defense firm, began his opening defense by promising to present, as his expert witnesses, “the doctors who treat more of these patients than anybody around.” They would testify that Risperdal was, indeed, a lot more effective than Haldol or any of the other first-generation drugs.

“We went to the people that have treated adults, treated children,” McConnico continued, “and said, ‘What do you think?’ They’re not Johnson & Johnson employees. They’re just doctors that treat these folks.”

As for the higher cost of Risperdal, McConnico promised that his experts would provide this answer: “When we talk about cost-effectiveness … one other part of having a bad psychotic problem is what’s going to be called the negative effects of that psychotic problem. … A lot of people just suffer from absolutely no motivation. Kids don’t want to go to school. Older adults don’t want to go to work. … And every doctor that … we’re going to put here is going to say … we knew about these earlier drugs not taking care of the lack of motivation and ambition.”

“And what did the doctors do? You bet they kept giving the drug,” a lawyer for J&J told the court. “We don't run away from that. We admit it.”

McConnico then promised to disprove the idea that his client had pushed its product improperly: “It’s easy for somebody to get up and use a lot of words, but doctors that have to treat somebody day in and day out—and the idea that doctors don’t have their patients’ best interest foremost in their minds and they just want to help some drug company, doesn’t sail, doesn’t fly. And what did the doctors do? You bet they kept giving the drug. And that was the reimbursement. We don’t run away from that. We admit it.”

The J&J lawyer then tried to defuse the impact of the seemingly incriminating documents Melsheimer had previewed, offering his client’s answer to all the internal business plans and emails that seemed to belie its Credo.

“Now, are some of the call notes and some of the things that you’re going to see and already have seen—are they wrong? Talking about how to promote this with children. You bet they’re wrong. They shouldn’t have been done. They’re not defensible. Some of these people did make mistakes.

“It is a very large company. It has thousands of employees. And out of those thousands of employees, there were some mistakes, not a lot. They were pretty rare. They showed you some emails. When you have that big a company, are people going to write some emails that are a … little exaggerated in the heat of the moment? Yes. They’re correct. They’ve gone through millions and millions and millions of pages. And if you do that in any business, you’re going to pull out a few where people are exaggerating.”

It was not until the final minutes of his opening that McConnico turned to the heart of the case: “Now, let’s talk about TMAP. … Did Johnson & Johnson … help fund that? They sure did. That’s what they ought to be doing. They ought to try to see what the experts in the field are doing, and then they should tell people.”

“Folks,” McConnico concluded, “if it helps Texans stay in school, keep a job, stay out of a mental institution, not commit a crime, then it’s helped every one of us.”

McConnico had hung his case not on punching holes in Melsheimer’s story about TMAP, but on whether his experts could persuade the jury that, whatever the embarrassing emails or business plans generated by a few J&J employees said, everything that had happened to make Risperdal the antipsychotic of choice had improved the lives of their fellow Texans.

The ‘Two Million Dollar Man’ Stops the Fight

One of the early witnesses Melsheimer called was Joseph Glenmullen, the Harvard psychiatrist retained by Sheller who was now also working for Melsheimer and the Texas attorney general. With Glenmullen’s hourly rate approaching $600, “we called him the two million dollar man,” says whistleblower-plaintiff Allen Jones.

They got their money’s worth.

Glenmullen calmly spewed out a series of damning allegations, resulting from what he said was more than 3,000 hours spent reading thousand of pages of text and data related to Johnson & Johnson’s handling, or mishandling, of clinical data. For example, of eight footnotes to an article J&J had published claiming Risperdal was safer or no more risky when it came to diabetes, two of the actual studies referred to in the footnotes had reported data that demonstrated the opposite of J&J’s claim, Glenmullen asserted. The other six studies were paid for by Johnson & Johnson, and one of those “manipulated” the results by excluding some of the participants in the study to make the results look better.

Anyone in the courtroom watching Glenmullen probably couldn’t wait to see how the McConnico would cross-examine him, to get a sense of Johnson & Johnson’s side of all of this.

That never happened. Apparently, Johnson & Johnson in-house lawyers, who watched McConnico’s opening statement and then Glenmullen’s testimony, decided against risking more. Soon after Glenmullen stepped down from the witness stand on the evening of January 18, Jones’ lawyers called him up to their Four Seasons war room.

“It’s over,” they said. “The company settled.”

J&J had agreed to pay $158 million to make the Texas case go away.

“My first reaction,” Jones recalls, “was ‘Oh shit.’ I thought we could demolish them the next day with more from Glenmullen. I just wanted it to keep going.”

Jones—who told me he went to live in “a cabin in the woods with no running water” after getting fired in Pennsylvania—says his whistleblower fee was “reported in the papers as twenty million. … The lawyers got 40 percent of that, then taxes took a big chunk.” His bottom line was about $8 million, he says, speaking from what he describes as a “modest” historic house he restored on 270 wooded acres in the Florida panhandle.

Jones had won the lottery, and Johnson & Johnson had avoided having a jury rule on its conduct.