Hardball

A ‘Hired Bazooka’

- Question:Mrs. Pledger, I think you told our jurors that during the time that you’re taking Mr. Pledger to doctors while he was on Risperdal, none of his doctors ever diagnosed gynecomastia?

- Benita Pledger:I never heard of gynecomastia. And, no, they did not.

- Question:At some point … you saw a commercial on TV for a Plaintiff’s law firm about Risperdal and lawsuits running? … And it had a phone number 1-800, call if you have taken Risperdal?

- Pledger:It had a number.

- Question:And they would file lawsuits?

- Pledger:That’s what the commercial was about, yes.

- Question:And, Mrs. Pledger, it’s true that the first person to tell you that Risperdal caused your son’s gynecomastia wasn’t a doctor, it was a plaintiff’s law firm?

- Pledger:True.

Johnson & Johnson was fighting back.

The Pledger trial had begun in Philadelphia on the afternoon of Friday, January 23, 2015. The plaintiff and her lawyers were now facing off against Diane Sullivan, a partner at Weil, Gotshal & Manges, a 1,100-lawyer Wall Street firm.

At a firm known for tough lawyers, Sullivan has a reputation as one of the toughest. She began her career, after graduating from the University of Pennsylvania Law School in 1987, trying cases at a much smaller New Jersey firm. After a few years, she told me, she was hired by Weil, Gotshal when breast implant liability cases started proliferating because the firm wanted a woman with trial experience who could sit at the defense counsel’s table.

By now, Sullivan was widely recognized as a prime weapon for corporations defending high-stakes liability cases. One of her wins for Phillip Morris, in which she beat back a suit by Missouri hospitals seeking smoking-related damages, had earned her a “Litigator of the Week” profile in The American Lawyer. “She isn’t a hired gun; she’s more like a hired bazooka,” the magazine declared. Sullivan had already saved one drug company, AstraZeneca, in a suit involving Risperdal competitor Seroquel.

With Kline regarded as an equally zealous fighter for his alleged victims, the Pledger case promised to be a great battle.

It was also a mess—nothing like the smooth-flowing courtroom dramas on TV. Both lawyers constantly interrupted with objections, many of which forced a solicitous Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas judge named Rami Djerassi to referee prolonged, often heated debates between them.

During one argument, Sullivan told the judge Kline was “insane.”

Almost every morning was delayed by fights over what a witness would or wouldn’t be allowed to testify about. Snowstorms and even a courthouse fire drill threw things further out of whack, as did travel snafus delaying out of town witnesses, the need for some jurors to attend to personal business and the obligation of a school teacher-juror to conduct parent-teacher conferences. On some days, when witnesses were not available but their depositions had been taken, the jurors listened as junior lawyers from each side acted out the deposition transcript.

Two Questions

The case was not about Johnson & Johnson selling off label. That was what the qui tam false claim cases were about. This was a personal injury claim.

The jury was made up of six men and six women, of whom 11 were African American and one was white. They included a security guard, a clerk at Macy’s and a nurse’s aide. Their job was to answer two questions: 1) Had Johnson & Johnson known and failed to warn Austin Pledger’s doctor that Risperdal was dangerous when taken by children like him? 2) Had that failure to warn caused Austin’s injuries?

If at least 10 of the 12 answered yes to both questions, they would then have to assess how much J&J should pay the Pledgers in damages.

Reduced to those two questions, it all seemed simple enough. But this would be one of those cases in which arcane medical terms and arguments over multiple sets of data and complex government regulations would test the patience and acuity of any lay jury, just as it would test the lawyers’ ability to explain it all.

‘G-Y-N-E-C-O-M-A-S-T-I-A’

Kline may have been the just-recruited gun-slinger, but it was clear he had channeled Sheller’s anger about prolactin and Kessler’s version of the 20-year history of the company’s regulatory and marketing sins. Now, in his opening statement, he sought to combine that with the Pledgers’ personal story and spin it into a narrative the jury could believe in:

“Austin was an autistic boy, now a young man, age 20. There will be no dispute he has … the most loving, wonderful mother. …

“Austin has a deformity. … He has … female breasts. … You’ll be seeing photographs during the case. They are, I think, what we could describe as large, pendulous breasts, not some small, little thing, but a significant, for a male, deformity.

“Janssen made the drug Risperdal. It caused him to develop those female breasts. … The condition…is known as—and you’ll hear this word over and over and over again — gynecomastia, G-Y-N-E-C-O-M-A-S-T-I-A. … It is permanent unless they were to be removed by a significant surgery. … Either way, he has disfigurement. …

“Janssen knew all the time that he was taking the drug … that this drug … had a greater incidence of the condition of gynecomastia than any of the other antipsychotic drugs. … [T]hey say it in their own internal documents. …

“Janssen Pharmaceuticals visited this doctor 21 times and never told him … the drug was known to raise—and I’m going to give you a little bit more than you might want at first, but I have to tell you—peak prolactin levels … that directly correlated to gynecomastia. … They never told Austin’s mom. They never told Austin’s doctor. …

[E]very time you see that picture, you look and you see, what do his breasts look like?. … Is this something that was right?”

Kline then delved into the details, risking turning off the jury with data about the prolactin study and the disputed Findling article. But he spiced it up, teasing the jury with what he previewed as an email from “the MBA lady whose name is Binder [who] said at one point that there’s a nauseating amount of gynecomastia.”

Kline closed with this plea: “When you’re dealing with the most fragile among us … in a drug that isn’t even approved for the indication, and you find a problem, a big problem, do you open the window for everyone to see in or do you try to pull the shades?”

Sullivan wasted no time hitting back.

“You heard Mr. Kline talk for about an hour or so and he said a lot of bad things about the folks at Johnson & Johnson and Janssen,” she began. “And that’s too bad. And it’s easy for people to kind of throw mud and say a lot of bad things about folks in the interest of winning a lawsuit and—”

Lawyers are rarely allowed to interfere with opening or closing statements. But Kline jumped from his seat. “Objection, your honor, right from the beginning. This is not an outline of evidence. It’s an attack.”

“I will grant some leeway … in an opening argument,” the judge replied. “You may proceed, Ms. Sullivan.”

Proceed she did. After all the settlements, followed by all the bland statements from the PR people, and the vague assurances from Gorsky in his deposition that everything his company did had been “appropriate,” the battle was on:

“It’s easy to throw a lot of allegations out there, but it’s going to be for you to decide what’s the truth, what’s the evidence. …

“Mr. Kline spent about an hour talking, and maybe some of you noticed, there’s one thing that he didn’t talk about … and that’s the label that was on the medicine from the very beginning. …

“I think Mr. Kline said the medicine wasn’t FDA-approved. It was FDA-approved from the beginning. It wasn’t approved for autistic kids until later, and we’ll talk about this. But from the beginning, it was approved by the FDA for adults. And on that FDA label from the beginning, in the precautions section—when the FDA approves your label, there’s different sections of a label, and the two most important are precautions and warnings. …

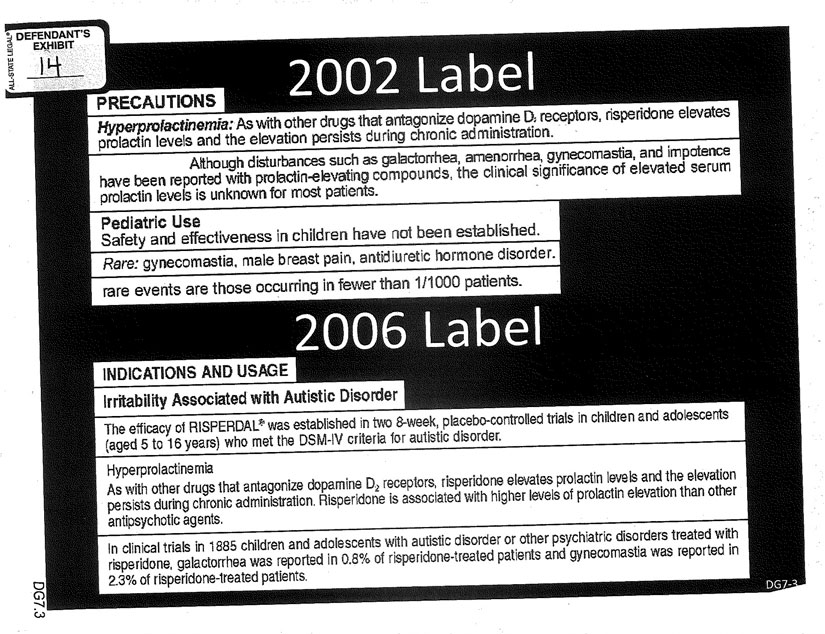

“For ten years before Mr. Pledger took the drug, in the precautions section of the label that this doctor had, that’s on every bottle of medicine that leaves the factory, that’s in every doctor’s office … it said—and Janssen and J&J told people—‘that risperidone elevates prolactin,’ and ‘gynecomastia had been reported.’ It was there right from the beginning in black and white. …

“Mr. Pledger’s doctor testified he knew about both of those risks. He didn’t know everything in the world. But he knew about the two risks that we’re talking about in this case. Hormone elevation of prolactin and gynecomastia. And so you’ll get to see that label as part of this case.”

Sheller and Kline recall that they were stunned by Sullivan’s argument. Was she really going to rely on the label approved in 1994, which had only said that gynecomastia was “rare,” meaning that it occurred in one-tenth of 1 percent of cases or less?

Sullivan knew from reading Kessler’s report in anticipation of the trial that he was on deck to testify that the company had studies as early as 2000—two years before Austin Pledger got his prescription with a label that still said “rare”—that showed 5.5 percent rates of gynecomastia among boys. She knew that the label had been changed in 2006 to admit that the gynecomastia rate was 2.3 percent, not “rare”—just as she knew that Kessler was ready to testify that that 2.3 percent rate was still too low and had been derived by distorting the studies. And she knew that Kessler was prepared to testify that the Findling article had hid damning data about the relationship between elevated prolactin and gynecomastia.

Was that the best she could do?

No, it wasn’t, as the rest of her opening demonstrated. The old label wasn’t really her defense.

The judge had told both sides that the case should be limited to a failure, if any, to warn about the dangers, if any, of Risperdal when Austin’s doctor had prescribed the drug.

“If your defense is the kitchen sink, they’re going to be able to bring in a washer and dryer,” the judge said.

But now, Sullivan pivoted to a much broader argument: that the risks were worth it and that any warning about side effects, no matter how mild or dire, had to be weighed against Austin’s desperate plight.

She was going to use sympathy for the boy to help her case, rather than hurt it.

In his deposition, Gorsky had talked about how Risperdal was his company’s response to parents who were “at the end of their rope” in trying to cope with troubled children. Apparently, that was going to be Sullivan’s rationale, too:

“[A]utism is a devastating mental illness. … You’ll hear that Mr. Pledger … can have shrieking, screaming, head banging, tantrums … that last anywhere … from 45 minutes to two hours and could occur as many as eight times a day.

“You’re going to hear that doctors talk about the fact that autism kind of walls these children off in some way from the rest of the world. … And you’re going to hear that Austin had a very, very low IQ. So he really—he really got the short straw in life, the fact that he got autism and he also was developmentally disabled. …

“And so his mother … went to this doctor and said, ‘Help. Is there a medicine for my son?’

“And Dr. Mathisen had treated other kids like Austin who had autism, and he had some success with Risperdal. It was approved for adults, but it was being prescribed for kids by many doctors….

“It’s hard to have parents agree to put their kids in studies that you need to do to get a medicine approved. … And so doctors like Mr. Mathisen, Mr. Pledger’s doctor, would prescribe medicines—what they call off-label—for things that they weren’t yet approved for….

“Aspirin was originally approved by the FDA as an over-the-counter medicine for headache. But then doctors figured out … that it could reduce heart attacks and strokes. So doctors would tell some patients: Take an aspirin a day. … And that’s what was happening with Risperdal. Mr. Pledger’s doctor and a lot of doctors were prescribing Risperdal for kids off-label. Why? There was nothing else.

“And what happened when Mr. Pledger started taking Risperdal? Unbelievable. And you’re going to see from the medical records … the benefits and the change in this child from Risperdal were dramatic and incredible.

“Risperdal worked for this kid and made his life and his family’s life and his colleagues in school, his classmates, his teachers’ life better. … And, you know, parents with kids who have problems like this, they have horrible choices.”

Kline could not stay in his seat. “Your honor, objection,” he shouted. “This case is about the warnings. We’ve heard 15 minutes about how great the drug was.” Again, the judge overruled him.

Then, Sullivan went a step further, describing what she said were the terrible side effects of the drug Austin had been put on after the doctor decided he was gaining too much weight from Risperdal.

This time, Judge Djerassi sustained Kline’s objection. He told Sullivan to stick to an outline of the case she was going to prove, rather than make arguments about other drugs that were not part of the case.

But Sullivan then threw both the judge and Kline a curveball. In fact, she intended to make that her case, she said. She was going to present expert witnesses to opine on a comparison of the risks of various anti-psychotics. Her point would be to prove that no matter what the warning for Risperdal had been or should have been, the doctor had been right to prescribe it.

This was exactly what the judge had gotten both sides to agree in advance not to contest, because it had nothing to do with a more basic failure to warn. If they got into arguing all of that, the case would become a free-for-all about the efficacy and safety of an entire drug class.

As Judge Djerassi told Sullivan after the jury had been excused, “If your defense is the kitchen sink, they’re going to be able to bring in a washer and dryer.”*

Yet Sullivan pressed on, taking most of the rest of her opening to highlight Austin’s desperate straits, how well Risperdal had worked and how much riskier any alternative drugs would have been. That, in fact, might have been a good defense strategy; one could imagine a jury getting so mired in the science of deciding which among many alternatives was the riskiest drug that it decided it could not definitively rule against Risperdal.

Once Sullivan was finished, Kline vehemently renewed his objection to how Sullivan was trying to change the nature of the case.

Describing himself as “the son of a doctor” who understands these issues, the judge said that if Sullivan insisted in going that route, he was prepared to manage the open-ended trial that would result. “I’m here all summer,” he said.

Then he offered Sullivan an additional warning, having to do with the fact that the trial was supposed to be about what J&J had warned doctors about, not the relative merits of competitive drugs and the conduct of the companies that sold them: “The fact of the matter is that I don’t think that’s going to be beneficial for the defense, because in the end … if it can be shown by this plaintiff that the other drugs had sufficient warnings on these type of issues and you didn’t, that is devastating.”

In case she had not gotten the message, he added this ominous observation about the trouble that this kind of trial might bring for Johnson & Johnson: “That is a multi, multi, big-time … potential verdict very different from the little case we’re having here in this trial. … I know you are an extremely fine attorney and you’re very experienced. Everybody knows who you are. So therefore, I’m just letting you know that these are decisions that your team has to make.”

“Understood, your honor,” Sullivan replied. She had tried to turn the case into something entirely beyond the issues the jury was supposed to decide, and the judge had stopped her in her tracks. For the rest of the trial, there would be no experts called to talk about how much better Risperdal was than the other drugs. Instead, Sullivan would try to convince the jurors that a mother’s understandable, if unworthy, hiring of a 1-800 trial lawyer to extract big bucks from her careful, caring client should not be rewarded based on some “cherry-picked” data touted by a hired gun expert witness.

‘I’m a Naïve Person. I Think People Are Good.’

Lawyers on both sides knew from his report what former FDA Commissioner David Kessler’s testimony was going to be.

But Benita Pledger didn’t.

Austin’s mother would spend the nearly five weeks of the trial watching the testimony all day, then retiring to a Holiday Inn. The longest she had ever been away from her son had been six days. However, she did not want to return home on weekends, she later told me, “because it would confuse Austin for me to come and go so much. … We just told him I was visiting my sister.”

The lawyers hadn’t told her much about her case, except that it looked promising. “They kept telling me how it was going to help all the others, because it was first,” she recalls. “But I didn’t have any idea of the details.”

On January 28, she began to grasp the details, or at least the details from her side’s perspective. Amid repeated objections from Sullivan that were overruled by the judge, she and the jury now heard David Kessler recite the history of the FDA rebuffing J&J’s efforts to get Risperdal approved for children, from before he was prescribed the drug to after he had begun taking it. She heard how the company had procured articles and speeches from academic luminaries to boost Risperdal sales to children. She became increasingly upset as Kessler continued in such painstaking detail that Kline’s questioning stretched over almost four days.

Kessler took the jury through his explanation of the evolving drafts of the Findling article, the creation of the new table that eliminated the boys who were 10 and over but kept the original denominator that included all the boys, and the untrue conclusion that elevated prolactin had not been shown to cause gynecomastia. “My real concern,” Kessler concluded, “is that you run data and then you get a series of results. … And then you have those results. What you don’t do is change rules after you get those results.”

Kessler proceeded to explain how the rates of gynecomastia had been manipulated, and how the other second-generation antipsychotics—the alternatives to Risperdal—did not have the same prolactin problems.

It was then, Benita Pledger recalls, that she “fell apart.”

“I’m a naïve person. I think people are good,” she says. “But I realized they absolutely knew. … I’ve tried never to cry, even when Austin had his worst fits.”

Sheller’s daughter, Lauren, who is a lawyer at her father’s firm and was sitting next to their sobbing client, took Benita out into the hall to collect herself.

Kessler’s testimony about the manipulation of the numbers was not lost on the jury. “Kline showed it to us pretty clearly with the FDA guy,” a woman who became the jury’s forewoman told me later. “He just repeated it over and over, and there was a chart of some kind that he used. You could see it—the thing with the numerator or denominator or whatever. You could see what they had done.” (The forewoman requested that her name not be published.)

Kline also had Kessler walk through what now seemed difficult to refute: how, all of that other evidence aside, the simple text of the changed 2006 Risperdal label was itself proof that the company had failed to warn adequately before then, when Austin had gotten his prescription—because by 2000 the company knew from clinical studies what it needed to know to include those additional 2006 warnings.

The real drama came next: Sullivan’s cross-examination of Kessler. The former FDA commissioner’s report and, now, his testimony, were at the heart of the plaintiffs’ assault on the Johnson & Johnson Credo. How would Diane Sullivan shake him?

First, she moved to strike his testimony altogether. Despite how Kessler might have put the jury to sleep with his slog through an avalanche of numbers and percentages, Sullivan protested that he had only offered his “gut opinion.” The judge denied her motion.

Sullivan did get Kessler to concede that lots of studies of children taking Risperdal showed no gynecomastia. But that allowed him to point out that those were studies of patients taking the drug over short terms, when no gynecomastia was likely to develop.

When Sullivan tried to question the importance of the study that had paid “special attention” to prolactin, she got trapped into having him reiterate why Johnson & Johnson should have changed its label and added a warning once it saw that study.

She even grilled Kessler on whether gynecomastia was “serious” enough under FDA rules to require a warning, whereupon the former commissioner was happy to opine why it was.

Throughout, he was unemotional, even clinical. Never raising his voice. Never using a gratuitous adjective.

Sullivan could not shake Kessler’s conclusions about how her client had mishandled the data or otherwise dent his aura as an “expert.” The transcript of her cross-examination of Kessler is here so you can decide for yourself. But here’s an example of how she kept failing to score:

- Sullivan:Dr. Kessler, you agree … it’s not right to cherry-pick out pieces of information and not tell the whole story?

- Kessler:When it comes to safety—let’s say you have a red leg, your leg is all red and inflamed—and I don’t mean to be personal, right—I have to look at that leg, okay. So of course my attention is selected on when there is a positive result.

Sullivan even failed with the standard attack on the other side’s experts as unprincipled hired guns: “You just cut and paste your report and stick in the companies, right?” That allowed Kessler to point out that he had only testified for plaintiffs suing drug companies in three of seven prior cases in which he has appeared as an expert. Then, he added, “But to say that I’ve testified each and every time the same way, I mean, I’ve been here for three days, I can assure you, no case has been like this.”

“I thought he was by far the best witness,” recalls the jury forewoman.

In short, the first days of the trial did not go well for Johnson & Johnson and Sullivan. But she had a surprise in store that could completely upend the case.

The Penile Enlargement Guru

By now, Benita Pledger had mostly given up trying to figure out what all the lawyers’ arguments with the judge were about. She only knew that they ate up long stretches of time before the start of each day’s proceedings and during the breaks when the jury had been excused.

As usual, on the morning of February 3, just before a doctor who had examined Austin was to testify as an expert for the family, there was a heated discussion among the lawyers and the judge that Benita did not fully grasp. When it ended, one of her lawyers came over and whispered, “How fast can you get Austin on a plane with Phillip [his father] to come up here? We need to have a new doctor examine him.”

Diane Sullivan had just sprung an objection on Kline and Judge Djerassi that belonged in the hardball litigators’ hall of fame.

More than a year before, Sheller and Kline had retained an endocrinologist, the type of doctor who diagnoses gynecomastia, as an expert witness. Sullivan’s team had taken his deposition in April 2014, more than nine months before the trial had started.

But on the eve of his scheduled testimony, the Johnson & Johnson lawyers had informed their opponents that Sullivan was going to move to disqualify the doctor. Her objection had nothing to do with his qualifications. Rather, it was because he lived and was licensed in California, not Alabama.

As the J&J lawyers explained to their stunned opponents, under an obscure Alabama statute—which, it later became clear, Sullivan and her team had known about for nearly a year—the doctor had arguably committed a felony, because examining Austin in Alabama in preparation for his testimony could be considered practicing medicine in Alabama without a state license. When Kline had told the doctor (described by Kline as “a semi-retired practitioner”) that night that the opposing lawyers might report him for committing a felony, he had refused to testify.

Kline was outraged, but there was little he could do except promise the judge that he would find another doctor who would examine Austin in a matter of days, so as not to delay the trial too much.

However, Sullivan now objected to what she called Kline’s “last minute” pulling of a witness and substitution of a new doctor in his place. She insisted that Kline should now have no expert witness, meaning he would have no way to establish that Austin had gynecomastia, let alone present evidence that Risperdal had caused it.

“The plaintiff sending an expert to Alabama when he was not licensed under applicable Alabama law is not extenuating circumstances,” Sullivan declared. And allowing a last-minute substitute would be “enormously prejudicial.” Sullivan also protested that the new doctor Kline was offering up—the only one he could find so quickly—was a plastic surgeon, not an endocrinologist.

When the judge overruled her objections, she demanded a mistrial, which would mean she would get to start the trial over.

“It’s the first time I ever saw a lawyer try anything like that,” Judge Djerassi told me.

“My word,” Kline replied, using a phrase he would deploy often in the trial to express a mix of outrage and surprise. “We have been at this for years. And they knew about this issue, as the Court knows, a year ago and they are the ones who sat on it in ambush.”

The judge rejected Sullivan’s protests, making no secret of his disapproval of the surprise attack, especially one that had harassed a bystander-witness.

“It’s the first time I ever saw a lawyer try anything like that,” Judge Djerassi told me.

When Sullivan later ridiculed the plastic surgeon’s credentials in her closing argument and pointed out to the jury that the plaintiffs had not been able to find an endocrinologist, Kline immediately objected.

This time, the judge lost his cool: “The conduct by the defense on that entire episode was very, very disturbing,” he told Sullivan. “I found there was … character assassination. I would not permit him to come and testify with you screaming he could go to jail for ten years,” he added, implying that he would explain the situation to the jury during his jury instructions. Which he did: At the beginning of his charge to the jury, he told them that “it was suggested to you again by Ms. Sullivan that the plaintiff could not produce an endocrinologist and suggested that they could not because they could not. You are instructed to disregard that line of argument in its entirety as it is not accurate and it’s disingenuous based on matters of law that occurred outside of your presence.”

“In 37 years practicing law I never heard a judge say something like that to a jury about another lawyer’s closing argument,” Kline says. (Sullivan refused repeated requests to comment about the trial.)

Nonetheless, Austin Pledger had to be examined again, and quickly. “My husband drove to the airport, and they got on a plane that night,” Benita recalls. “It was really upsetting. … You know how Austin can’t deal with changes in his routine.”

What was still more upsetting to her was how Sullivan mocked the plastic surgeon as a “penile enlargement” specialist when he testified after examining Austin.

“She said penis so many times,” Benita Pledger recalls. “They were trying to make a joke out of this.”

It was true that Dr. Mark Solomon’s website bragged of his talents in using a “penile stretching device,” and “grafting procedures” that “widen the penis.” But Solomon also practiced across the spectrum of plastic surgery needs, including performing reconstructive surgery for free at Philadelphia Shriners Hospitals for Children, and he boasted an array of academic credentials and hospital affiliations.

Once on the witness stand, despite Sullivan’s repeated cross-examination of his penile surgery skills, Solomon also proved to be a by-the-books diagnostician of breast tissue.

“She said penis so many times,” Benita Pledger recalls, “that it was almost funny. But I didn’t think it was funny. They were trying to make a joke of this.”

“The lawyer was too harsh with the penile doctor,” recalls the forewoman. “She badgered him, insulted him. It was too much. … He was a real doctor.”

*Correction: The piece initially stated that Judge Djerrasi made this statement in front of the jury. He in fact only said it to the lawyers after he had sent the jury home for the day, because, as he noted in an email, it would have been "extremely prejudicial" to the defendant to do otherwise. We regret the error.