Blowing

Past

The Label

‘Otherwise The Sky Would Be The Limit’

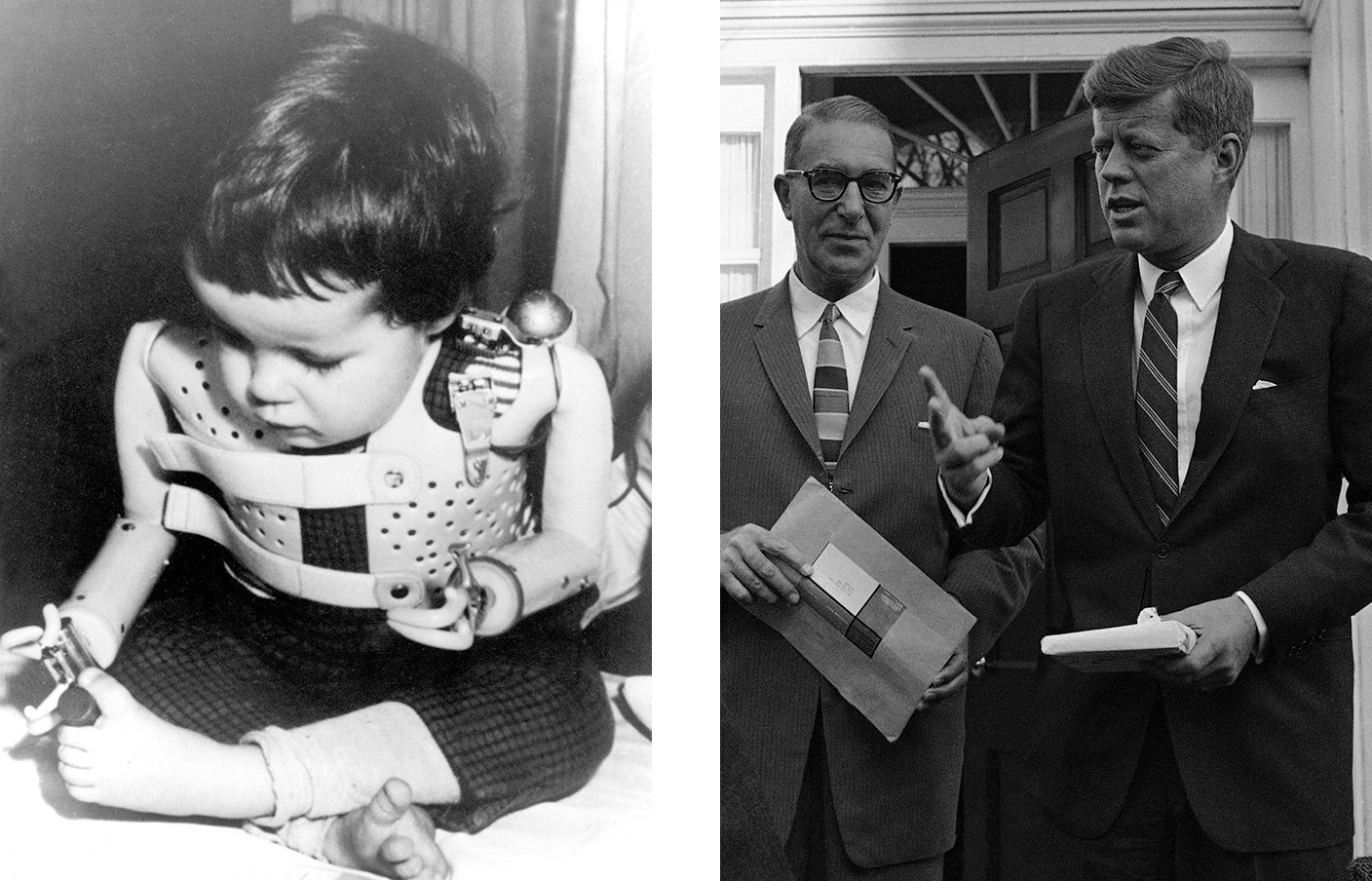

In 1961, newspapers around the world ran stories (accompanied by horrific images) of deformed babies whose mothers had taken a drug to curb nausea during pregnancy called thalidomide. A vigilant FDA inspector had refused to approve thalidomide for sale in the United States because she was worried about its safety. But the thalidomide story, along with persistent new reports about other drug company abuses, were highlighted in hearings convened by Senator Estes Kefauver, a Tennessee Democrat. This created a political climate for clamping down on the emerging pharmaceutical industry, and in 1962, President John F. Kennedy strengthened the landmark Federal Food and Drugs Act of 1906.

A key provision of the new law made it a crime for drug companies to promote drugs to doctors for patients with illnesses for which the drug, according to its FDA-approved label, was not intended and approved for use.

Kefauver explained his concern about tight labeling and the need to police off-label sales this way: Once a drug was approved for any initial purpose, “the sky would be the limit and extreme claims of any kind could be made” about the safety and effectiveness of selling that drug for other uses without the FDA vetting it. That would undermine the benefit-risk analysis that the new law required the FDA to weigh. A drug might be worth the risk of certain significant side effects if it helped alleviate a schizophrenic’s hallucinations or urge to commit suicide. But it might not be worth those risks if it was used to treat a restless nursing home patient or a child acting up in school.

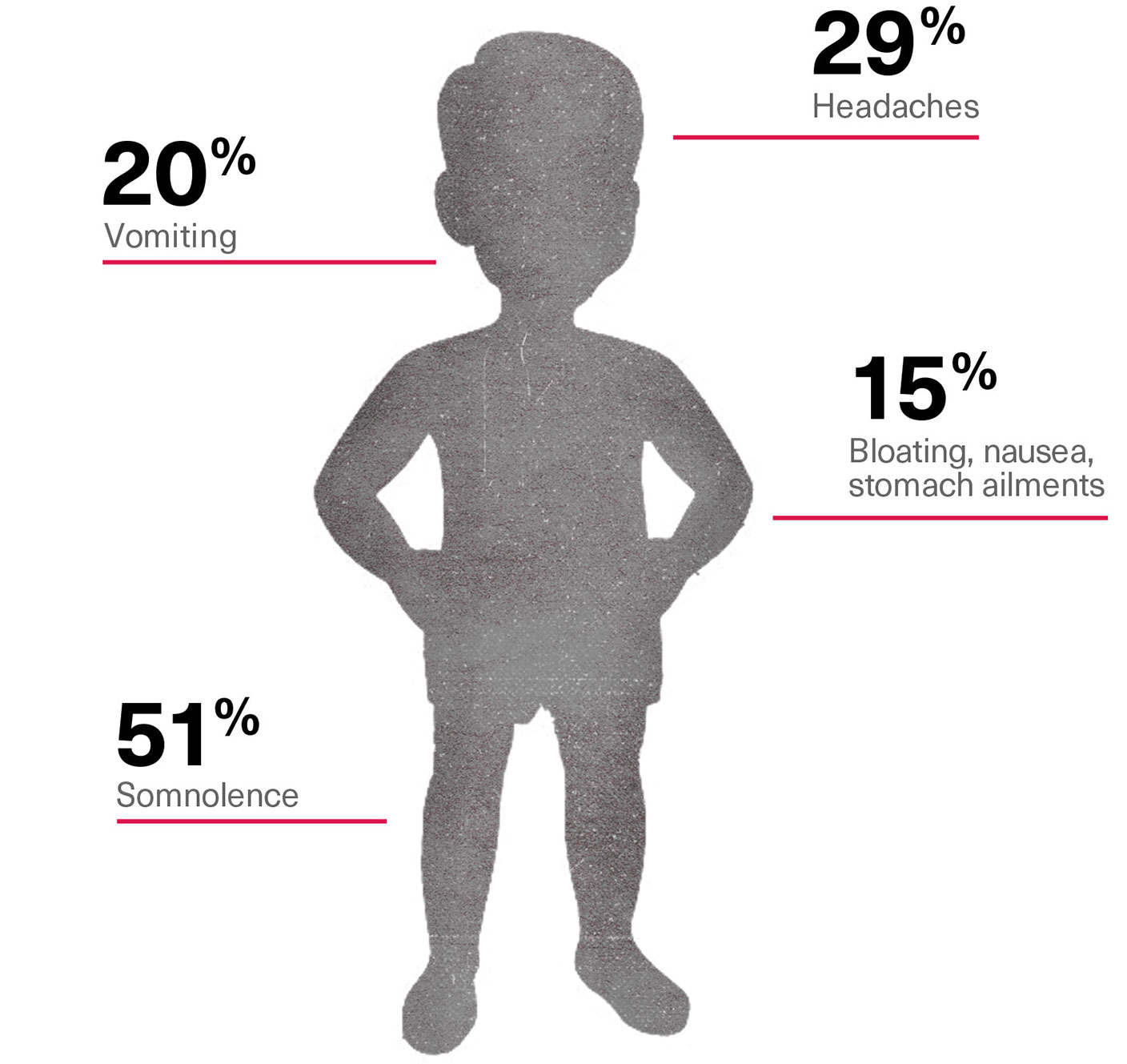

For Risperdal the risks were substantial. Even in the earliest trials, the data showed significant rates of side effects. These included involuntary twitches, somnolence, diabetes and, most frequently, significant weight gain. In the elderly there was a particularly high risk of strokes and other heart-related diseases. In children, Johnson & Johnson’s own data would ultimately count somnolence (51 percent of the time), headaches (29 percent), vomiting (20 percent) and bloating, nausea or other stomach ailments (15 percent), among other side effects.

Risperdal Side Effects in Children in Early Trials

Moreover, if the drug companies were not required to get a labeling change from the FDA before selling a product more widely, there would be little incentive to undertake the clinical studies necessary to test the safety of the drug when deployed for those new uses. Why test whether the drug is safe for children if you can market it to children anyway?

However, while under the law, the FDA controls drug companies, it cannot control doctors. A physician can prescribe any drug approved for sale by the FDA, even if the doctor wants to use it for a purpose not described as an intended use on the label.

The rationale is that the final decision on use, dosing and risks versus benefits should be up to the physician. He or she can review the detailed FDA-approved label and make a decision based on an evaluation of the patient’s needs. Of course, the doctor risks additional liability by prescribing an off-label use. But such decisions are not unusual, especially because many in the medical community perceive a lag between a drug being identified as a promising solution to a given illness and the FDA’s confirming it.

Thus, for Johnson & Johnson to expand the market to reach its business plan targets, doctors had to be sold on the value of Risperdal in populations that were not included on the label as the drug’s intended users. Yet it was a crime for the company to sell the doctors on the benefits of using Risperdal to treat those populations.

“We started looking hard for ways to go after these customers—pediatricians, nursing home doctors, mental health facilities, even school guidance counselors,” a former Janssen salesman recalls. “We had to.”

A Magic Algorithm

Beginning in 1995, Janssen executives focused on a quick-win priority: make Risperdal the new drug of choice at state-run Medicaid programs that provide healthcare for the poor, including children in state-run mental health facilities and the elderly in state-run nursing homes. Promoting the drug quietly to institutions, rather than broadly to thousands of individual doctors, was more efficient—and less likely to arouse the suspicions of the FDA.

The goal: get Risperdal at the top of the states’ lists of approved drugs, called formularies, even though the price would be 40 to 50 times the cost per dose of first-generation antipsychotics, such as Haldol, that were now available as generics.

The path: Have a group of doctors, sanctioned by a state, evaluate all the available drugs and determine that the state’s Medicaid prescribers should use Risperdal as their first choice.

In part with $1.8 million in funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation—which was independent of the company, although it was a major shareholder—Johnson & Johnson found its first willing partners among Medicaid and health officials in Texas, some of whom were paid consulting fees by J&J’s Janssen unit for their involvement. Thus was born the Texas Medical Algorithm Project, or TMAP.

Within a year, Johnson & Johnson was setting up what one internal memo called PR “SWAT” teams that churned out news releases and offered press availabilities with Texas officials touting the new “Expert Consensus Guidelines”—a manual that put Risperdal at the top of the recommended and approved list for doctors with Medicaid patients suffering from schizophrenia.

The extra cost of the new drug was worth it, the doctors had concluded, because Risperdal was so much more effective than Haldol or other available options.

The payments to doctors and the PR firms were supplemented by contributions to patient advocacy groups, such as the Texas chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, which is known as NAMI. One dividend was a conference in Austin, called a “Clinical Best Practices” symposium on “New Medications: Impact and Future Value in Treating Severe Mental Illness.” The program presented the virtues of TMAP to mental health doctors from across the state. The Texas division of NAMI was featured as the lead sponsor. It wasn’t disclosed that Janssen had paid for the event, and that some of the doctors who were dispensing their clinical advice or were in the audience chatting up the program with other doctors were on the Janssen payroll as consultants.

The FDA had warned Johnson & Johnson not to claim that Risperdal was more effective than Haldol. Now, the doctors in this new Texas program, financed by Johnson & Johnson, would do that.

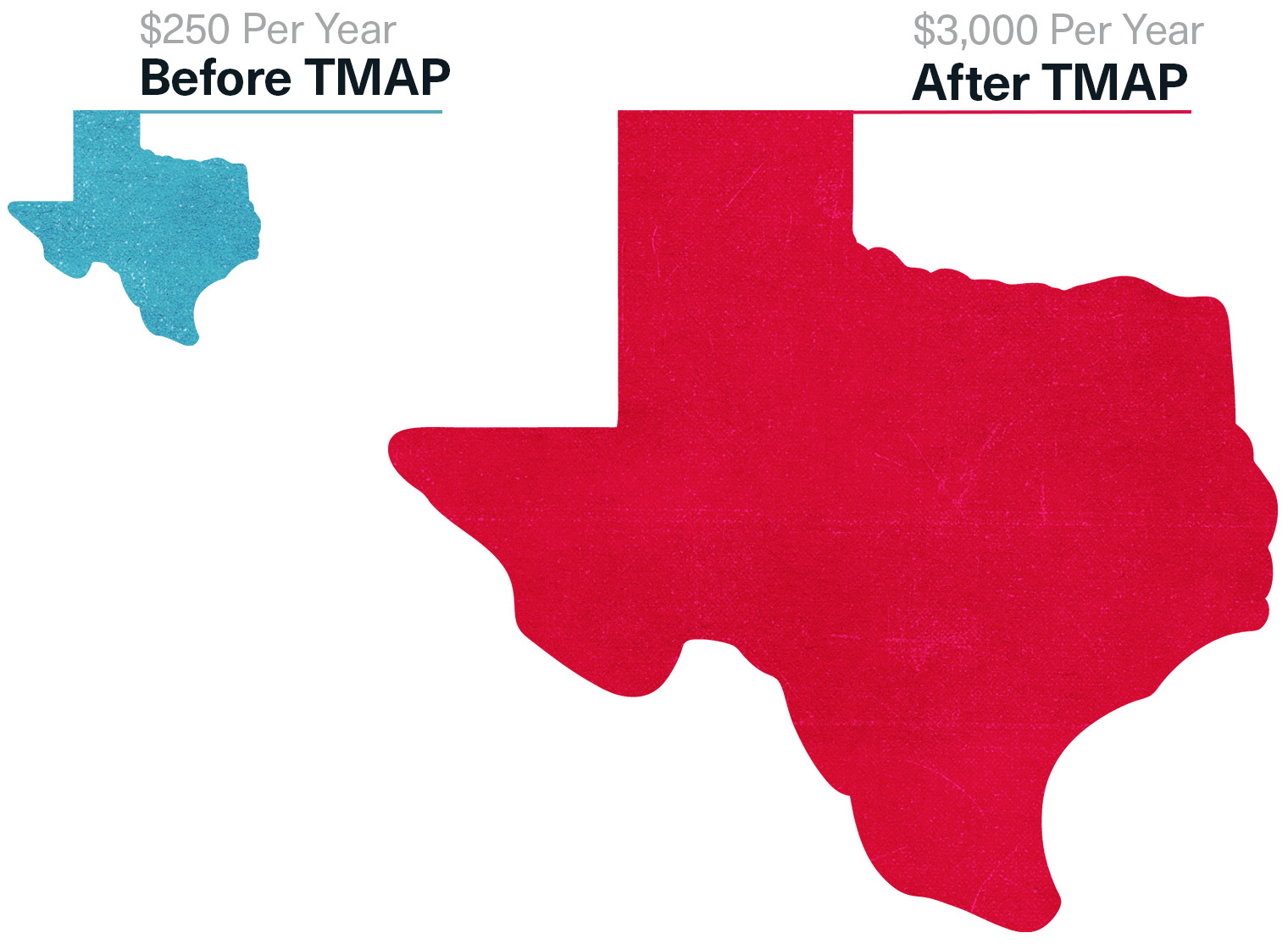

Before and After TMAP: How Much Texas Medicaid Spent Per Patient on Antipsychotic Drugs

By 1999, Texas’ Medicaid payments for antipsychotic drugs would soar, with Risperdal having the dominant market share. The state now paid $3,000 a year for each of its patients, compared to $250 a year for the generic first-generation drugs like Haldol. Some of J&J’s competitors were “watching in awe at what J&J did,” recalls one executive at another Big Pharma company. They also began chipping in for the “research,” and getting their products up near Risperdal on the preferred list.

Meantime, Johnson & Johnson paid the Texas doctors who had launched TMAP to give speeches to colleagues across the country urging them to implement their own “MAPs.”

‘Active Intervention’ at Nursing Homes

Another way for Johnson & Johnson to market Risperdal off-label without directly soliciting individual doctors involved nursing homes and a company called Omnicare.

By the mid 1990s, Omnicare had become a colossus in a growing corner of the healthcare industry. The company, then based in Covington, Kentucky, provided pharmacy management services for nursing homes with hundreds of thousands of patients across the country. As executives at Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen pharmaceutical division reminded each other in an internal memo, Omnicare was the dominant player in deciding which drugs were dispensed to those patients. But, as one email would later explain, “In order to have the Omnicares of the world drive market share … it must be financially [worth] their while.”

On April 8, 1997, Janssen signed an agreement with Omnicare that included an “Active Intervention Program” that explicitly paid Omnicare to favor Risperdal over other drugs a patient could be given. The point, the contract stated, was “to appropriately shift market share to [J&J]’s Product.”

Doctors would be offered paid speaking fees based on the number of Risperdal prescriptions they wrote.

Taken literally, the adverb “appropriately” should have rendered the deal meaningless. When this agreement was signed in 1997 and when it was renewed thereafter, the Risperdal label hadn’t changed since the FDA had first approved the drug in late 1993. The label warned that the drug had not been determined to be safe for elderly patients. And as the FDA’s Dr. Leber had written to Johnson & Johnson two years earlier, the regulators didn’t want it to be used to treat symptoms associated with dementia or other behavior disorders, such as agitation. Yet the Johnson & Johnson literature distributed to Omnicare pharmacists urged it to be used to calm restless patients.

After the deal was signed, Janssen began paying Omnicare tens of millions of dollars in rebates and fees in return for multiples of those amounts in sales of Risperdal, paid by American taxpayers through Medicare and dispensed to Omnicare patients. By 1999, an internal Johnson & Johnson email explaining the Omnicare relationship would refer to the nursing home pharmacy management company as “an extension of [the J&J] sales force.”

The Active Intervention method was deployed across the country at the retail level, too. Doctors would be offered paid speaking fees based on the number of Risperdal prescriptions they wrote. The government investigation of Risperdal sales later unearthed one email from a Johnson & Johnson salesperson that was typical of the approach. She told her supervisor that she was going to promise one doctor that if he raised his Risperdal market share from 16 percent to 50 percent in the coming 12 months he could become a paid speaker.

A West Point Man In Charge

Beginning in 1997, the sales manager of the J&J division responsible for Risperdal sales in the U.S. was Alex Gorsky, a West Point graduate and former army captain. Slim, good-looking and described by everyone I spoke to at the company as a hard-charging, natural leader, Gorsky had started his J&J career as a salesman. He then earned an MBA from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania while working his way up the sales ladder by constantly hitting his targets and ensuring that the growing number of sales reps working under him hit their targets, too.

As internal emails and business records would later reveal, as sales manager, Gorsky was involved in all key Risperdal sales and marketing initiatives, including meetings with Omnicare executives about the progress of their Active Intervention contract and its renewal. By 1998 Omnicare was Risperdal’s single biggest customer.

It was at about this time that the company began to eye another weapon to get beyond the reach of the FDA’s label restrictions: The First Amendment.

Free Speech Warriors

In November 1997, the Washington Legal Foundation, a non-profit that champions free markets, filed suit charging that the FDA’s guidelines on promoting drugs off-label deprived drug companies of their First Amendment right to offer information to doctors and deprived doctors of their right to receive it.

Although the foundation does not reveal its donors, Chief Counsel Richard Samp told me that the pharmaceutical industry “has supported some of our efforts.”

The suit did not challenge the FDA’s prohibition on creating explicit marketing plans and sales pitches for off-label use. Rather, it was aimed at the agency’s guidelines declaring that drug companies might be subject to charges if they disseminated materials, such as articles from medical journals, that reported favorably on a drug’s off-label uses unless the doctor had first asked for the information.

In July 1998, federal district court judge Royce Lamberth, a conservative appointed by President Ronald Reagan, prohibited the FDA from enforcing its guidelines on First Amendment grounds. But the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit threw out that order after the FDA—clearly afraid of further damage from the courts—claimed that its guidelines were only meant to tell drug companies what kind of conduct would not be prosecuted as off-label marketing.

Conversely, the agency declared, the guidelines did not mean that articles and other promotional materials that did violate the guidelines would, in and of themselves, be considered illegal off-label marketing, because the guidelines were not meant to prohibit speech. Instead the guidelines were meant to signal the type of speech that, to the agency, might be evidence of an off-label selling violation that needed to be investigated.

Put simply, the case did not, at least for now, free the drug companies to do whatever they wanted, including create whatever sales pitches they could dream up, if their intention in doing so was to penetrate unapproved markets. And it certainly didn’t sanction business plans devoted, as the law put it, to introducing a drug into commerce for a purpose not approved by the FDA.

But that didn’t keep the executives and their Risperdal salespeople from acting as if it did.

Full Throttle

Beginning in 1998, the company’s Risperdal promotional efforts began to escalate. Campaigns were launched to deploy sales teams to use explicit messages to pitch doctors, such as pediatricians, likely to have patients in the drug’s off-label target populations.

An 83-person Risperdal ElderCare sales team was formed—creating a countrywide unit whose explicit, unabashed mission was to get Risperdal into the mouths of an off-limits population. Its only targets, according to internal budgets and sales plans, were doctors who primarily treated the elderly or who were medical directors at nursing homes.

Johnson & Johnson knew, and Wall Street knew, that they only had seven more years to cash in on Risperdal before its patent expired.

The Johnson & Johnson sales force is required to submit reports of all customer contacts. In 1998, a New York ElderCare salesperson wrote: “Discussed how Ris[perdal] is effective and safe in the Tx [treatment] of behavior disturbances in the elderly, especially those with dementia.” Another in California said: “Left a note introducing myself and ElderCare [division] with Ref[erence] to Risp[erdal] for Geriatric hostility/behavioral problems.”

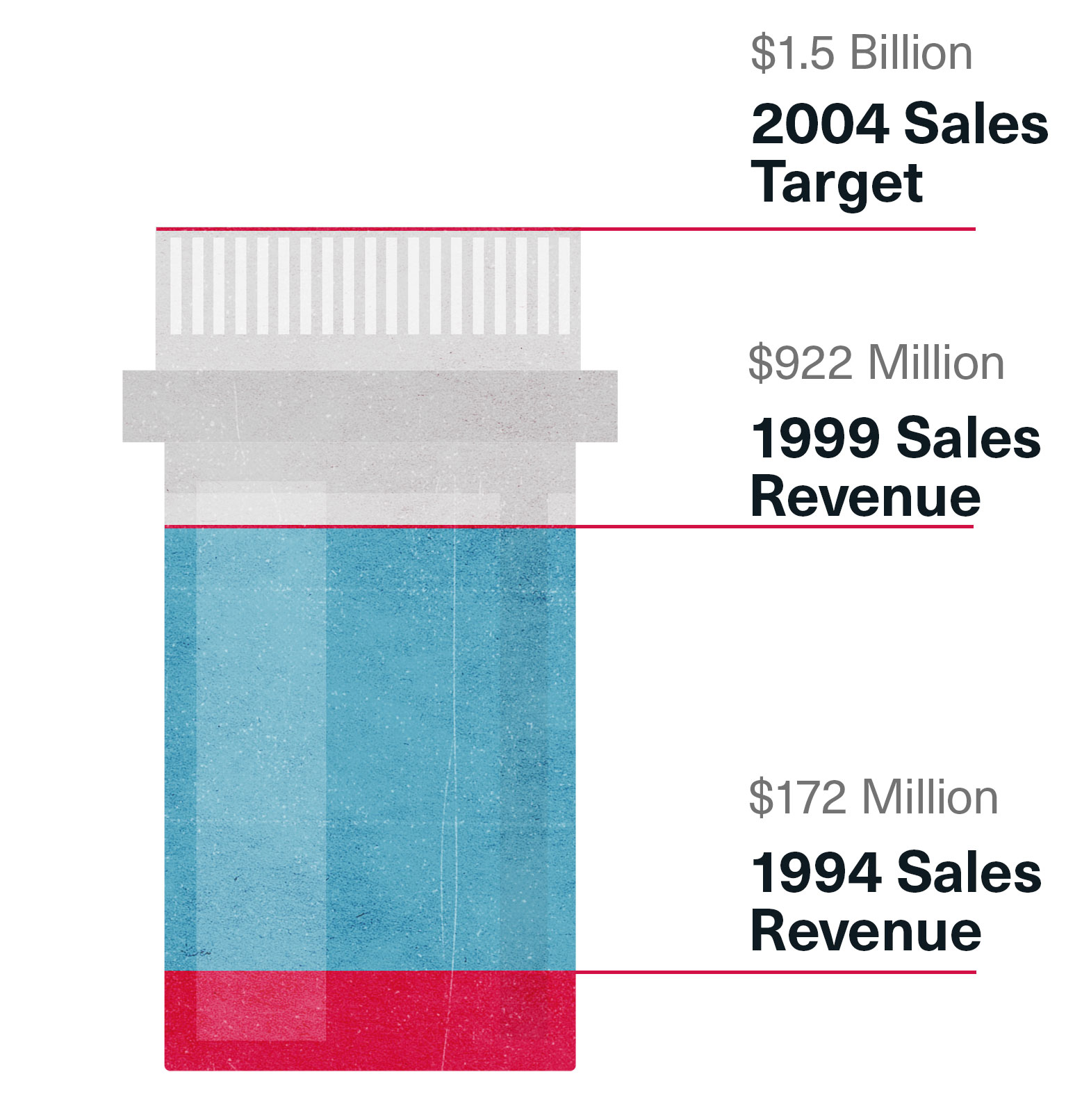

By 1999 Risperdal sales in the U.S. were $892 million, up from $172 million in the 1994 launch year. But there was still a long way to go to reach the $1.5 billion in U.S. sales Johnson & Johnson was now targeting for five years out, in 2004. “The better we did, the more they ratcheted up the targets,” one salesman recalls. “The word was we had to go full throttle, pull out all the stops.”

Reaching for $1.5 Billion

A factor already weighing on Janssen executives and their bosses at Johnson & Johnson was the expiration of the Risperdal patent at the end of 2007. They knew, and Wall Street knew, that they only had seven more years to cash in on their drug. After that, Risperdal would go the way of Haldol.

One problem they encountered in 1999 had to do with Omnicare’s Active Intervention agreement.

Under Medicaid’s rules, a drug company must sell drugs given to Medicaid patients at a discount of either 15.1 percent off of the regular wholesale price or at the “best price” given to any other buyer if that price is lower than the 15.1 percent discount.

An Aug. 25, 1999, email from a J&J executive overseeing the Omnicare relationship worried that all the rebates that had been given to Omnicare might drop the actual price it was paying below that 15.1 percent threshold. That would mean that J&J would have to lower the price it charged for Risperdal for all other Medicaid patients across the country. According to an internal J&J memo, Omnicare was responsible “well over $100 million” in annual business, and it was insisting on being paid what it was owed under its deal for all of that volume.

So within two months, the company devised a way around the law: J&J would instead pay part of what it owed Omnicare under a different contract that ostensibly had J&J buying “data” from Omnicare related to Risperdal prescriptions. It was later argued by the government, using documents investigators had subpoenaed, that J&J was already getting this data for free.

J&J found avenues less subtle than data purchases to get money to Omnicare. In June 1999, an Omnicare senior vice president emailed a Janssen executive requesting $45,000 for a summer golf outing for Omnicare senior executives on Amelia Island in Florida.

“We will use these funds to further advance our expertise in management activities … ” the Omnicare VP wrote in a letter that his J&J contact could pass on to the accountants.

‘Glad you are keeping your discussions around dementia’

Johnson & Johnson managers regularly rode along with salespeople for meetings with doctors, keeping copious notes on everything from the cleanliness of their cars to how well they stuck to the pitches disseminated from the home office. One report, written in early 1999, noted that a district manager had told a rep, “I was glad to see that you are keeping your discussions around dementia, because we are a geriatric sales force that focuses on treatment of behavioral disturbances associated with dementia.”

Reports like this from the field were the first clear signs that when it came to Risperdal, sales and not the Credo seemed to have become the company’s mission.