Sales

Over

Science

Putting the Risks in ‘Tiny Font’

By the beginning of 1999, Johnson & Johnson had expanded the ElderCare unit to 136 salespeople from 83, and the materials they were using to pitch doctors had caught the FDA’s eye. On January 5, Lisa Stockbridge of the FDA’s Division of Drug Marketing, Advertising and Communications wrote to Janssen’s director of regulatory affairs complaining that “presentations that focus on this population are misleading in that they imply that the drug has been found to be specifically effective in the elderly population.

“Risperdal is indicated for the management of manifestations of psychotic disorders,” Stockbridge added. “However, Janssen is disseminating materials that imply, without adequate substantiation, that Risperdal is safe and effective in specifically treating hostility in the elderly.”

Stockbridge also cited a sales tactic that seemed to stand R.W. Johnson’s Credo of putting patients first on its head. Janssen’s materials, she wrote, “are lacking in fair balance because the risk information appears in pale and tiny font at the bottom or back of a journal ad or other presentation.” For example, she wrote, “the warning regarding tardive dyskinesia”—involuntary movements such as facial grimacing—“is minimized,” and “the claim[s] that ‘Risperdal can enhance daily living’ or that [it] offers ‘quality control of symptoms for daily living’ are considered to be false or misleading.”

Regulators noted that J&J had “failed to fully explore and explain what appeared to be an excess number of deaths” among the elderly treated with Risperdal.

Janssen responded by assuring the FDA that it was going to review its sales materials. However, the company argued that some information about the use of Risperdal among the elderly was appropriate because so many doctors were prescribing it for their patients.

In March, Stockbridge wrote back that her agency “has considered Janssen’s argument and is not persuaded.” She particularly called out a sales flyer the FDA had since discovered headlined “Hostile Outside, Fragile Inside.” That pitch, she noted, “implies without adequate substantiation that Risperdal has been specifically shown to be effective in treating psychotic elderly patients with hostility.”

“The safety and efficacy of Risperdal in the elderly,” she added, was “not particularly examined in ‘fragile’ individuals.”

Meanwhile, another unit of the FDA told Janssen in January 1999 that its request a year earlier to extend the label for treatment of the elderly was denied because it had failed to “fully evaluate the safety of [Risperdal] for use” by that population. The regulators also noted that the company had “failed to fully explore and explain what appeared to be an excess number of deaths” among the elderly treated with Risperdal. The deaths the FDA was referring to mostly had to do with strokes and other heart-related fatalities.

The rejection letter again warned Janssen not to market the drug for use by seniors.

Boys With Breasts

Through the late 1990s, a different team of Janssen salespeople continued to promote Risperdal to the other forbidden population: children.

“Sold him on efficacy and safety in children,” one Michigan call report bragged.

“Remind[ed] her that Risperdal is very effective and safe because she sees lots of children and adolescents,” a Maryland sales rep reported.

These were not instances of overeager troops straying off message. By 1999, more than 20 percent of Johnson & Johnson’s $892 million in U.S. Risperdal sales were to the pediatric market.

Tone Jones, a Texas-based Janssen manager, would later testify that the directive to focus on children came straight from the home office. Jones—who would win a 2001 sales award at a ceremony presided over by Alex Gorsky—was asked in court, “In your experience, would promoting Risperdal off-label to children get you fired?”

“No,” he replied.

“Would it get you a bonus?”

“Yes,” he answered, whereupon he produced a letter from a regional supervisor awarding him a bonus based on “your performance quotient of 131.05%.”

Hormone Issues

By the late 1990s, studies of people using Risperdal and its competitor anti-psychotics had started to reveal that young patients showed an increase in levels of prolactin—a hormone that at its normal levels enables women to produce breast milk. The data seemed to suggest that Risperdal was the worst offender. Raised prolactin levels in young boys, it was thought, might cause them to grow female breasts, a disease called gynecomastia.

On October 19, 1998, Gorsky, who was Janssen’s vice president of sales for its CNS (central nervous system) division, led a “Risperdal Brand Strategic Planning” meeting. One of the action items on the agenda was the need to examine the effect of these raised prolactin levels. According to the minutes, Eli Lilly—which was marketing the competing drug Zyprexa and whose salespeople were telling doctors that Risperdal had a prolactin problem—had three studies in the field to help drive home this competitive advantage. With that in mind, Janssen decided to push ahead with its own studies of whether Risperdal affected prolactin levels in children, and what side effects, if any, elevated prolactin might cause.

At the same time, the company focused on rounding up respected academics who could aid the cause by touting the results as they came in and make Risperdal the prime choice for pediatricians regardless of what the FDA label said.

‘Not Someone to Jerk Around’

Chief among the academic luminaries Johnson & Johnson began to covet was Joseph Biederman, a pediatric psychiatrist. For more than a decade, Biederman had done pioneering work on the theory that behavior disorders among children and adolescents–such as attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—were the result of chemical imbalances in the brain that could be addressed with strong prescription drugs, such as Risperdal.

Biederman was born in Czechoslovakia in 1949 and moved to Argentina when he was six months old. He completed medical school in Buenos Aires when he was 22 and went on to an internship at Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem. He then came to the United States to train as a child psychiatrist at the prestigious Boston Children’s Hospital, which is part of the Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital.

By the time Biederman got onto Johnson & Johnson’s wish list, he had been credited as the author or co-author of hundreds of medical journal articles on the use of pharmaceuticals to address children’s behavioral issues. In 2005, The Institute of Scientific Information would rank him number one for scholarly citations related to ADD or ADHD.

Biederman’s supporters considered him a genius, even a savoir. “I’ve had people from around the country who were old friends or even people I hardly knew calling me to help get them an appointment with Joe for their kid,” one former executive at Massachusetts General told me. His detractors, who generally were people worried about the effects of plying children with drugs, considered him a menace.

“Biederman is a very powerful national figure in child psych and has a very short fuse,” John Bruins warned.

Johnson & Johnson’s early encounters with the strong-willed Biederman had not gone well.

On November 17, 1999, John Bruins, who was Janssen’s liaison to the medical community in New England, emailed his supervisors asking them to expedite the approval of a $3,000 check to Biederman. The doctor had been promised the money, Bruin wrote, for his appearance at a symposium at the University of Connecticut, where he had spoken on the promise of drugs like Risperdal.

“Dr. Biederman is not someone to jerk around,” Bruins warned. “He is a very powerful national figure in child psych and has a very short fuse.”

As Bruins went on to explain, Johnson & Johnson had lit that fuse in the past—when expanding the FDA label, rather than working around the label, had been the company’s priority for getting Risperdal into the children’s market. “Three or four years ago,” Bruins wrote, “Janssen … requested that he put together a study to evaluate RIS [Risperdal] in the child and adolescent population. He submitted a thorough and lengthy proposal, which amounted to approximately $280K. We dragged our heels on his request … for over a year. He finally received a standard ding letter.

“By the time I found out,” Bruins added, “and went to see him, his secretary advised me of his fury. The sales representative who called on him and I took an hour of verbal beating. I have never seen someone so angry.

“Dr. Biederman is Head of Adolescent Psych at [Massachusetts General]. Since that time our business became non existant [sic] within his area of control,” Bruins continued, adding this zinger: “He now has enough projects with [J&J competitor Eli] Lilly to keep his entire group busy for years. Although I occasionally call on him and invite him to our [paid Advisory] Boards, he acts with skepticism about our sincerity.”

Biederman was quickly paid the $3,000, and the company began talking with him about what would become a multi-million dollar project to promote Risperdal, using his, Harvard’s and Mass General’s name.

14 Percent of All of J&J’s Profit

Getting Biederman on the team was part of a still-more aggressive business plan for the year 2000, drafted in July 1999.

The plan targeted $1.059 billion in U.S. sales for 2000, through 707,000 in-person sales calls to doctors who would prescribe 452 million pills or oral doses, priced at about $2.50 per dose. Total costs—including $51 million for “public relations, grants, sales support and medical education programs,” and $14.3 million for free samples—were budgeted at just $103 million. That included the salaries of all the salespeople and the cost of the drug itself, which was so low that it did not merit its own line item. The cost of PR and other marketing, about 12 cents per dose, was about twice the cost of the actual drug, according to other internal J&J budget analyses.

Profit for Johnson & Johnson ($1.050 billion in revenue against $103 million in costs) was projected at about $950 million. If that target was achieved, the yield from this one product would be 14 percent of all of Johnson & Johnson’s total earnings for the year across all of its divisions.

The first objective listed in the plan was that “Risperdal will be the antipsychotic treatment of choice for both psychotic and non-psychotic disorders.”

Non-psychotic disorders represented the “sky’s the limit” problem that Senator Kefauver had had in mind in 1962 when he wrote restrictions against off-label sales. These less serious maladies were not included on the label as indicated treatments for the drug because the FDA was not convinced that treating them was worth the risk of Risperdal’s side effects.

Nonetheless, the next line of the company’s business plan listed dementia and conduct disorders (which include ADD and ADHD) as key targets, with the next page spelling out a grab bag of other off-label disorders for Risperdal to target, such as stuttering.

The business plan noted that Lilly’s competing drug, Zyprexa, was beating Risperdal in market share, 34.7 percent to 25.2 percent, for bipolar-related prescriptions, the treatment codes most associated with children’s more general behavior disorders. Thus, the strategies listed under “Bi-Polar Disorder” included “strengthen opinion leader and advocacy support for RISPERDAL.” That was where big-name academics—including Biederman—would play lead roles.

Another goal for the coming year was to “maximize and grow Risperdal’s market leadership in geriatrics and long term care.” Risperdal was already well ahead of Zyprexa in dementia market share, with 50 percent of the entire market. The goal was to boost that share still higher, to 57 percent, with sales of $302 million.

The nursing home pharmacy manager, Omnicare, was a big part of that plan. By the summer of 2000, Johnson & Johnson would sign a new, more extensive deal with the company. One of the J&J executives on the account crowed in a memo about “Omnicare’s ability to persuade physicians to write Risperdal in the areas of Behavioral Disturbances associated with Dementia.”

He continued: “Omnicare, Inc. has demonstrated its ability to partner in a true sense of the word and has generated well over 100 million dollars of Johnson & Johnson pharmaceuticals annually.”

Selling a ‘Chemical Straitjacket’

The Food and Drug Administration consistently rates high among federal agencies in employee morale. Officials there, along with the doctors and scientists on the front lines reviewing drugs, like to think of themselves as professionals dedicated to a mission—keeping dangerous products off the market and helping drug companies get good products into the market. However, when they think they are being conned, they can be tough.

That was their posture on March 3, 2000, when about a dozen product development scientists and regulatory executives from Johnson & Johnson met to talk about Risperdal and children. Once again, the J&J team’s goal was to get the label extended to include “conduct disorders” in children. This would not only sanction the marketing that the company was already doing; it would also extend the overall Risperdal patent for six months under a law that gives pediatric drugs longer protection from generics.

According to minutes of the meeting recorded by someone on the J&J side of the table, the FDA officials wasted no time shooting down the premise of the proposal: “The FDA questioned the validity of conduct disorder (CD) as a diagnosis and even the concept of CD as a disorder,” the minutes reported, “because it is just a list of behaviors, mainly aggressive behaviors that annoy others. … Their main concern is that Risperdal or any other product would be used as a chemical straitjacket.”

“They really didn’t believe it,” recalls one FDA official who was at the meeting. “We were basically saying their plan, whatever data they presented, was not legitimate because conduct disorder could mean anything.”

According to multiple documents later produced in lawsuits and investigations related to Risperdal, it was following this meeting that the company stepped up its efforts to legitimize conduct disorder as a diagnosis in the academic medical community. That was what Biederman had made a career of.

Popcorn and Legos

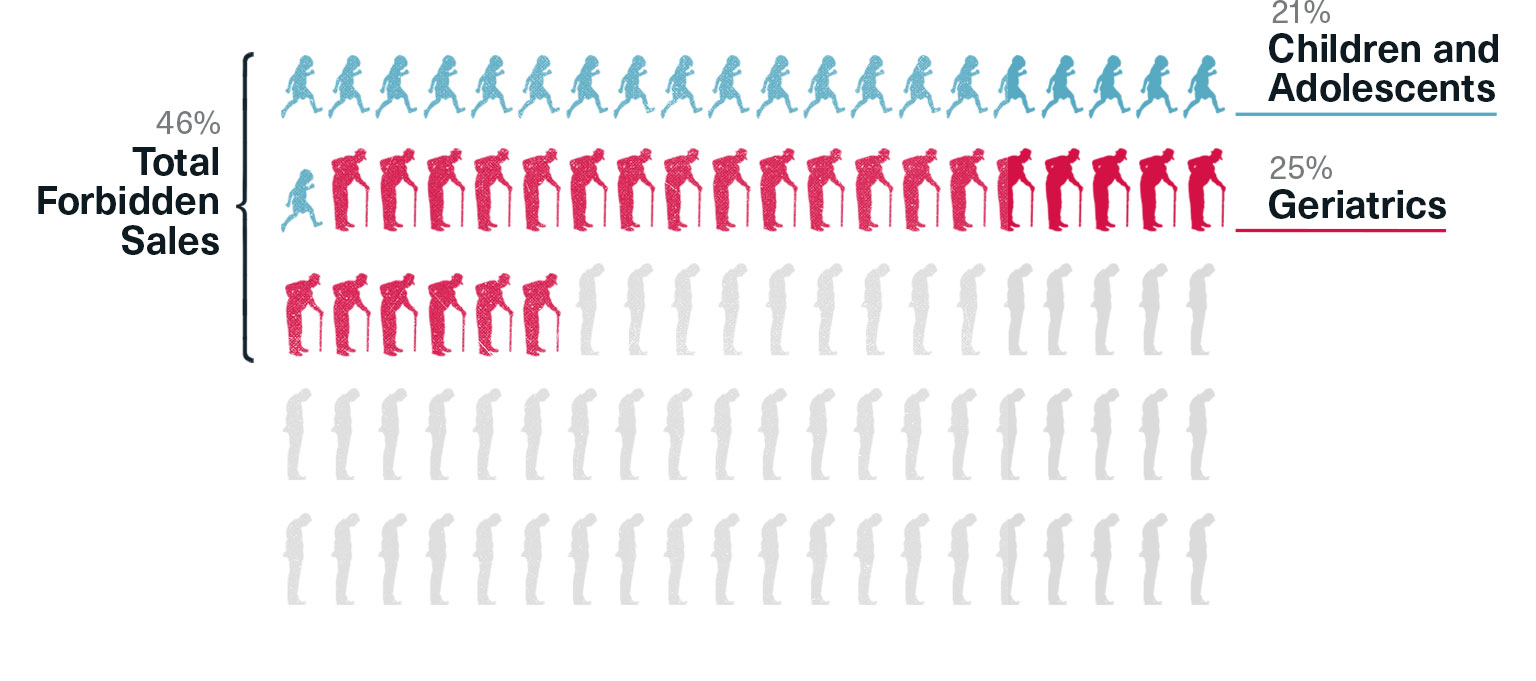

By the fall of 2000, 21 percent of Risperdal being sold was going off-label to children and adolescents, and the sales teams had been told that expanding that market was the company’s highest priority.

Houston sales manager Tone Jones would later testify that “the message from headquarters” was that “hostility, aggression, agitation” was a “significant opportunity” for the company to achieve what was by then a target of nearly $3 billion in annual U.S. sales before the patent expired.

Jones brought a visual aid to spice up his testimony: a photo of popcorn, packaged and labeled as “Risperdal Popcorn,” to be given by sales reps to pediatricians. Its purpose, according to a sales primer, was “to butter up docs.”

The doctors who prescribed the most Risperdal were recruited to be paid speakers, Jones would testify, and were called “whales.” They were so important to the business, Jones explained, “that we needed to see them for sure on a weekly basis, if not every day pretty much.”

Another favorite sales tool that began to be distributed in the waiting rooms of whales, or prospective whales, he added, were Legos imprinted with a Risperdal logo.

In early September 2000, a Johnson & Johnson email celebrated the full implementation of the TMAP program that put Risperdal at the top of the recommended list of second-generation antipsychotics and first-generation generics for doctors giving these drugs to Medicaid patients in Texas. “Let the butt kicking begin,” wrote a Janssen sales manager.

By the end of 2000, Alex Gorsky’s Risperdal sales team had beaten its ambitious sales goal of $1.05 billion, coming in at $1.08 billion.

Sell the ‘Symptoms, not the Disease’

In September 2000, the FDA ordered a labeling change—but not one that J&J had pushed for. The agency told Johnson & Johnson that the indications on the label should be scaled back—from management of “psychotic disorders,” to just the “treatment of schizophrenia,” which is one of several psychotic disorders.

Of course, this technically constrained the market for Johnson & Johnson’s best-selling drug. But in the sense that the company was already selling into markets far beyond the label, it arguably didn’t matter. By the time the company implemented the FDA order in February 2002, a full 16 months later, the sales team had been prepared well. The pitch was now all about, as one salesperson put it, “the symptoms, not the disease.”

Doctors would be reminded that medical care was all about treating the symptoms that bothered their patients (or, in the case of nursing homes, the staff members who had to control patients). It didn’t matter whether a nursing home resident was acting out because she had Alzheimer’s or was just plain unhappy, or was acting out because she was among the less than 1 percent of the elderly who were schizophrenic. The pill would calm her down.

Bad Breast Numbers

In November 2000, Johnson & Johnson research scientists got troubling numbers related to the goal Gorsky and his team had set at the Risperdal “Brand Strategic Planning” meeting two years earlier. They had hoped that the scientists would generate data that would rebut the competition’s claim that Risperdal raised levels of the hormone prolactin to a degree that could cause young boys to grow breasts. But the largest study done yet by J&J of the effects of long-term Risperdal use among children and adolescents—in which, according to the study’s protocol, “special attention” was paid to prolactin—had now found that of 319 children, including 266 males, 8.6 percent of the males had developed gynecomastia, or breasts. When the final results including more participants were tabulated, the percentage of males was 5.5 percent.

Attention deficit disorder was no picnic, but doctors and parents might not think treating it was worth those odds of their son having to wear a bra.

Five and a half-percent was a big number. If 400,000 boys took Risperdal, that would mean 22,000 might end up with breasts. Attention deficit disorder was no picnic, but doctors and parents might not think treating it was worth those odds of their son having to wear a bra. And that risk was in addition to all the other known side effects already listed on the Risperdal label, such as somnolence, nausea or significant weight gain.

Worse, none of Johnson & Johnson’s competitors seemed to have the same gynecomastia problem.

Until that time, J&J had told the FDA that it had no information on the relationship between prolactin and gynecomastia other than that in its studies of all patients taking Risperdal—including adults—gynecomastia was “rare,” meaning it occurred one tenth of a percent of the time or less. And that, in fact, is what the approved label said about gynecomastia.

‘Driving Pediatric Acute Medical Education’

An updated Risperdal business plan that management signed off on in September 2000 unabashedly signaled that Johnson & Johnson would ignore the regulators and any bothersome data and keep going after children.

The plan described the small—but legal—schizophrenia market as “flat.” However, that did not present a significant hurdle, because schizophrenics were not the hard-charging sales team’s target. “The RISPERDAL Base business is rooted in the Schizophrenia marketplace,” the plan acknowledged—as if “legally allowed to be marketed in” really only meant “rooted.” But that would not be an impediment, because, the plan noted, “The child/adolescent … segment (19 years and under) is growing at a rate of 17% and is currently valued at approximately $340 million. Use of RISPERDAL in this segment has grown 50% in the past two years, and prescriptions in this category account for 20% of overall RISPERDAL use.”

The Risperdal Market in 2000

Children and adolescents were now the fastest growing segment of the market—and they accounted for 21 percent of all Risperdal users. The second fastest uptick was in the geriatric market, which comprised 25 percent of all Risperdal users. That meant markets that J&J was forbidden from promoting to accounted for 46 percent of all sales in the year 2000, a percentage that was likely to grow quickly because, as the plan noted, the legitimate market, schizophrenic adults, was “flat.” In fact, a study later published by the Journal of the American Medical Association would put the off-label percentage at 66 percent in 2001.

The plan then mapped steps to be taken in the coming year to “grow and protect share in child/adolescents via medical education initiatives and effective [sales] rep-targeting, with a year-end exit share of 70%.” Respected doctors—called “Known Opinion Leaders,” or “KOLs”—would be paid to “drive pediatric acute medical education” with a blizzard of J&J-financed articles, symposiums and supporting PR.