A

Multi-front

War

Heavy Up Top

Since he had begun taking Risperdal, Austin Pledger was having fewer tantrums. The reports Benita Pledger read from her son’s school reflected what she was seeing at home: “His frustration behavior has improved greatly,” his special education teacher wrote in April 2004. But it was far from a complete turnaround. Austin would still erupt in volatile behavior, biting himself or suddenly dropping to the floor and pounding his head.

Benita and Phillip continued to dote on him, and marveled at his ever-amazing feats of memory. He could now recite long passages from books that he was starting to be able to read. He amazed his parents almost every day by completing the required phrase, when just a few letter clues had been posted, as he watched his favorite TV show, “Wheel of Fortune.”

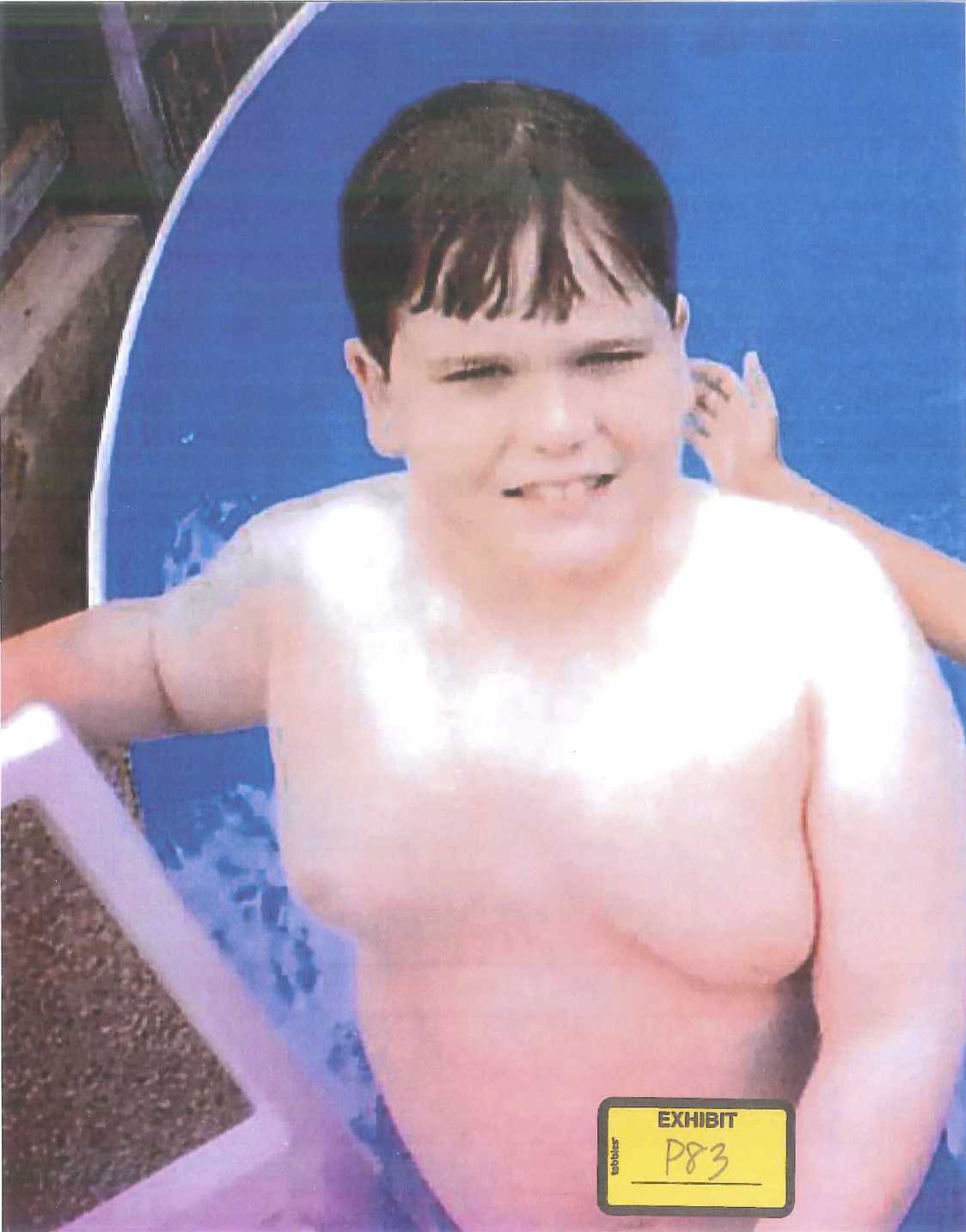

But despite Benita’s incessant efforts to control Austin’s diet, her son had gained an enormous amount of weight in the two years since he had started on Risperdal. Worse was where he seemed to be putting on much of the weight—up top, in his chest. “He started to get really self-conscious about it,” Benita recalls. When summer came and it was time to swim in the family’s above-ground pool, out back behind the house and the car repair garage, Austin’s parents began to realize just how self-conscious their son was.

At some point, recalls Phillip Pledger, his son “became so embarrassed about how he looked up top that he didn’t even want us to see him. So he began to wear a T-shirt, even in the water.”

Before then, however, Benita Pledger happened to snap a photo of him climbing out of the pool.

‘My Son Has Breasts’

While he pursued more evidence for the qui tam suit he had filed on behalf of Vicki Starr, and before he had ever heard of Austin Pledger, Stephen Sheller was on the lookout for more conventional personal injury cases he might bring—cases on behalf of patients who could claim to have been damaged because Risperdal had been sold to them off-label.

A mother called to say that she had noticed something strange about her son: He had grown female breasts and eventually needed a double mastectomy.

The sales reps who were his clients for the earlier qui tam case against Zyprexa, the Risperdal competitor, were useful sources for finding out what kind of damage Risperdal might have caused. They were well-versed in Risperdal’s rumored dangers, because those dangers had been part of their old sales pitches. They had harped on the point that patients who took Risperdal gained large amounts of weight and even ended up with diabetes. Before long, Sheller had a few prospective clients with possible diabetes claims against Risperdal.

Then, in the winter of 2004, the mother of one of those clients called to say that she had noticed something strange about her son. He had grown female breasts. By August he had been diagnosed with gynecomastia and had had a double mastectomy.

Sheller had never heard anything about Risperdal and male breasts and, of course, had no idea that Janssen’s top executives and scientists were by now fixated on the problem. “So I asked the Zyprexa guys,” he recalls. “And they said, ‘Yeah, that’s right. We’ve heard that, too.’”

Once Sheller figured out the medical term, gynecomastia, and then how to spell it, he tried, he says, “to read everything I could.”

Gynecomastia was on the way to becoming one of his causes.

It was during this time, while taping a television show talking about the evils of pharmaceuticals that Sheller met psychiatrist Joseph Glenmullen.

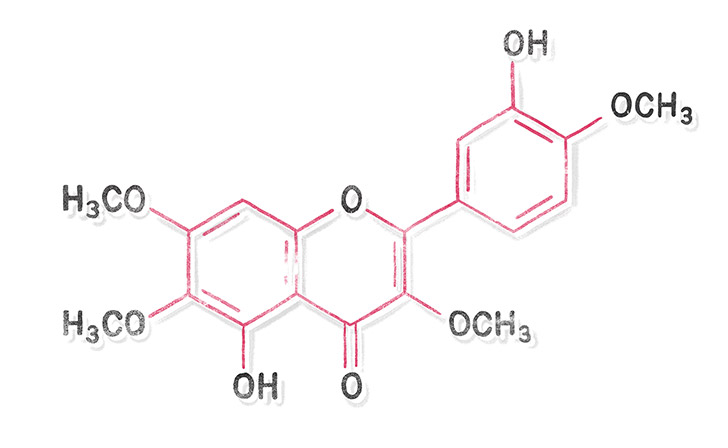

Glenmullen, who taught at Harvard Medical School and practiced at the university’s health service, had started to make something of a name for himself in medical circles as a skeptic of drug companies in general and of antipsychotics in particular. Glenmullen assured Sheller that he was on to something. Risperdal did raise levels of a hormone called prolactin, he said. Sheller had already read something about that.

“What about male breasts?” he asked his new friend.

Yes, Glenmullen said. From what he had read and heard from other doctors, it was likely that prolactin elevations would cause gynecomastia. Sheller kept digging—and kept talking up Risperdal among his trial lawyer friends, telling them to snoop around and send referrals his way.

The Billion-Dollar Hail Mary

On December 19, 2003—10 days after a Janssen salesman, making his bi-weekly visits, had dropped off another 1,592 sample doses for Austin Pledger’s doctor to try out on new patients—Janssen’s regulatory team had gone back to the FDA, in yet another effort to get children legally on to the Risperdal label.

However, the company’s strategy had changed. The rising sales numbers showed that Biederman’s evangelizing about conduct disorder had obviously encouraged pediatricians to dispense Risperdal. But it had not swayed the FDA.

If the application extended the patent by a half-year, it could be worth as much as $1.5 billion in additional U.S. sales.

So the Johnson & Johnson strategists threw in the towel on conduct disorders. Instead they proposed that Risperdal be labeled as appropriate for the treatment of a specific, acknowledged psychiatric illness in children: autism.

That market was small, but at least it would give their salespeople an ostensible reason for talking to pediatricians and pediatric psychiatrists. Besides, under the law, a new indication that included children would extend the fast-expiring patent by six months for all sales of the drug. If this application extended the patent by that half-year, it could be worth as much as $1.5 billion in additional U.S. sales before Risperdal went generic.

One of the arguments the Janssen scientists and FDA liaisons used in the new FDA pitch was that multiple clinical trials had now proven that Risperdal was safe for kids—and that any elevation in prolactin levels had not been shown to cause side effects such as gynecomastia. A prime piece of new evidence that they cited was the study that became the Findling article.

No More Sales Calls

In November 2004, Austin Pledger’s doctor and thousands of pediatricians, pediatric psychiatrists and pediatric neurologists like him around the country suddenly stopped getting sales calls from their Johnson & Johnson reps. At the same time, and with no explanation, the company suddenly eliminated incentive bonuses for Risperdal sales to pediatricians. The abrupt change seemed especially surprising because bonuses for sales of Risperdal had until now been set higher than those for sales of other products, reflecting what had been the company’s priorities since Risperdal’s 1994 launch and the drive to make it a record blockbuster.

The proposed label change covering treatment for autism in children had still not been approved, and by now people at Johnson & Johnson who focused on legal and regulatory issues had become worried about these off-label marketing efforts.

Eli Lilly was well into discussions with prosecutors over off-label sales of the drug Evista. An investigation into sales of Lilly’s Zyprexa, the key Risperdal competitor, was ahead of where the feds were on Risperdal. An investigation of another Risperdal rival—Astra Zeneca’s Seroquel—was also further along. These and other cases against competing drug companies for off-label sales were becoming public or were being talked about in the Big Pharma and corporate defense legal communities because the subpoenas were starting to fly.

All of that activity, plus the Times article about Allen Jones’ whistleblowing, had caused Johnson & Johnson and Janssen executives to order that the Risperdal off-label sales campaigns be throttled back.

Meantime, other plaintiffs lawyers across the country, feeding off of their professional grapevine, began gathering whistleblowers to file Risperdal qui tamsuits of their own, all focusing on the claim that the off-label sales constituted false claims against the government’s Medicare, Medicaid and other health care dollars.

Death of a Sales Manager

From mid-2004 through 2005, Vicki Starr made more trips to Philadelphia to meet with her lawyers. She was also taken to see federal prosecutors in the U.S. attorney’s office. “They recorded me for hours, asking really precise questions,” Starr says, “about the wording of sales pieces. How they were used? What we were told to say? How the bonuses were paid? How had the messages changed in the year after I started?”

A startling event in 2005 unnerved her. One morning Starr’s former sales manager did not show up for a scheduled ride-along with a sales rep. When the manager failed to call in or otherwise explain his absence, the sales rep went to the marina where the manager was living while going through a divorce. He found him dead of an apparently self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Starr knew that federal agents were already investigating her case. Had they questioned him? “Was it my fault?” she remembers thinking. “I knew he was going through a divorce, but I couldn’t get it out of my head.” No evidence would ever surface that the man’s death had anything to do with the Risperdal investigation, and officials at the U.S. attorney’s office in Philadelphia would not comment as a matter of policy on who might have been questioned by that time about the case.

By now Sheller was working on a plan to consolidate the various Risperdal qui tams around the country in one suit to be given to federal prosecutors in Philadelphia. At the same time he and the other lawyers were working on gathering individual plaintiffs, whose claims would be that they were damaged by the drug, into another large group.

Subpoenas Everywhere

By November 2005 Johnson & Johnson knew for sure that the company was in trouble. Prosecutors in Philadelphia issued a subpoena demanding everything related to the sale of Risperdal—business plans, emails, sales reports, clinical studies.

The prosecutors had still not officially entered the qui tam cases, despite the theoretical 60-day deadline for making a decision once a relator and his lawyer filed a case in secret. They had repeatedly convinced judges in the cases that they needed more time.

In January 2006 the Texas Attorney General weighed in, demanding that Johnson & Johnson produce what a subsequent J&J Securities and Exchange Commission disclosure called “broad categories of documents related to the sales and marketing of Risperdal.” Melsheimer had convinced the attorney general’s office to join forces for what would become a state qui tamalleging billions in false claims related to Medicaid payments to J&J.

Other inquiries and document demands poured in to J&J from Arkansas, South Carolina and California, among other states. Federal lawmen in Massachusetts soon joined the action when a whistleblower who had worked at Omnicare—the nursing home pharmacy manager that had negotiated that Active Intervention deal with Johnson & Johnson to increase Risperdal usage—had come to them with that story. The Boston prosecutors liked this one because it also might yield charges of Johnson & Johnson paying kickbacks to Omnicare.

Personal injury lawyers were piling on, too, using websites, Google search advertising, social media and TV ads to gather clients who could claim they had been injured by Risperdal—and in some cases the competitor drugs sold by Eli Lilly or AstraZeneca. (Their Google ads are still there; search “Risperdal lawsuits.”) On July 20, 2006, the national plaintiffs firm of Weitz & Luxenberg filed on behalf of 208 such alleged victims. The claim mentioned off-label selling, but focused on diabetes as the injury the plaintiffs had suffered. Gynecomastia was not mentioned.

Yet by now Sheller was becoming convinced that gynecomastia could be the more severe injury—and the route to a bigger payday. Proving the drug had caused diabetes would be difficult, because, as he recalls, “They did warn about weight gain. So once people gained weight, diabetes was a likely result apart from any chemical in the drug. I’m not saying it was not a cause or the cause, but it was hard to prove they had caused it without warning.”

But no matter what particular injury the suits alleged, all of them allowed the lawyers to join the hunt—via court-sanctioned pre-trial discovery—for damaging J&J documents.

‘Maybe This Was Not Going to Amount to Anything’

In 2006 and into the first half of 2007, Vicki Starr continued her meetings with government prosecutors in Philadelphia. The questions got increasingly specific and those asking them seemed increasingly serious.

Starr connected best with Charlene Fullmer, who had returned to government service after working six years at a corporate firm. Before that, Fulmer had been a lawyer at the FBI. By 2007, she was on her way to winning a slew of Justice Department and other government service awards related to, among other cases, her investigation of the other drug company qui tams that Sheller and other lawyers had brought to her office.

One colleague of Fullmer’s told me that Fullmer was especially incensed by the J&J case. Starr remembers thinking the same thing: “She looked shocked, she may have even said something like ‘wow’ when I told her they had set up a separate ElderCare sales unit.”

However, after those intense meetings with the prosecutors, Starr heard nothing and was asked to do nothing for the next three years. Sheller continually assured her that the government would come in—that these things take time. “We began to think that maybe this was not going to amount to anything, and that we should just go on with our lives, so we did,” recalls her husband, Jason.

Waiting and Guessing

A growing team of Johnson & Johnson defense lawyers from a half dozen outside firms waited, too. They had plenty to do, gathering the subpoenaed documents and contesting the demands whenever they could find some legal basis to do so. However, the real action would only come once the feds made the first move.

“In their minds, they had done nothing wrong,” recalls one senior outside lawyer who was working for J&J.

There was little the company could legally withhold, their lawyers said, unless somehow it was a privileged communication with a lawyer. That meant that all those business plans targeting dementia or children were fair game. So were the sales pitches, like the “Sleep Backgrounder” handout touting the drug’s potential for saving nightshift staffing costs at nursing homes, or the emails talking about Risperdal popcorn and Legos.

Based on what they had handed over, the Johnson & Johnson and Janssen executives who had helped to make Risperdal the company’s biggest hit could guess what the government might be planning to accuse them of. “But in their minds, they had done nothing wrong,” recalls one senior outside lawyer who was working for the company. “It was the doctors who made the decisions about who used the drug, not them. The docs were the ones who prescribed off-label. And they had a right to. All the J&J folks did was give them information—which is their First Amendment right.”

Wearing Down The FDA

On October 6, 2006, the FDA handed Johnson & Johnson a win. As the Janssen team had requested nearly three years earlier, the agency approved a change in the label so that it would now include treatment for “irritability associated with autistic disorder” in children and adolescents. It was now entirely proper for Janssen sales reps to tout the drug to pediatricians. Almost immediately, they resumed the sales calls they had suddenly abandoned two years before, although they were only supposed to talk about treatments for autism.

It is difficult to tell why the agency put aside its prior concerns about safety—other than that J&J’s repeated efforts in multiple meetings and exchanges of long position papers over more than 10 years finally wore down the regulators.

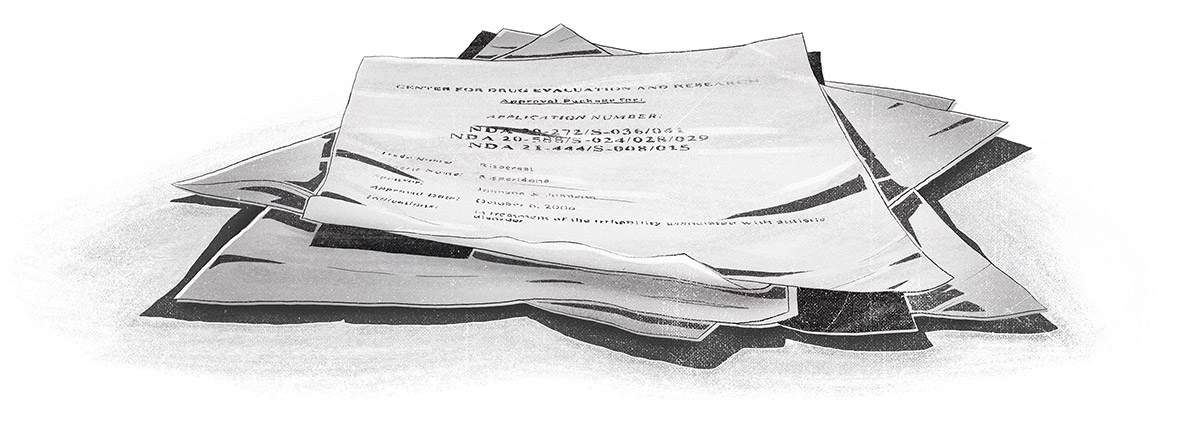

Records of the discussions with the FDA about the new autism application Johnson & Johnson had filed reveal that the J&J team was repeatedly asked about the dangers to children that had long concerned the FDA’s doctors, including raised prolactin levels. Their answers, and the agency’s vetting of those answers, raise questions whether, when billions of dollars are riding on a government decision far removed from the headlines, the public can rely on what is essentially an honor system—in which the sponsor of a drug is expected to shoot straight with its regulator when submitting data.

Notes recorded by the FDA of a December 7, 2005, meeting about the drug’s side effects when given to children reported that the J&J team had “argued that the expressed concern about unacceptable longer-term risks, in particular … hyperprolactinemia [elevated prolactin levels] … was not justified based on available data.”

An FDA memorandum reported that J&J had assured the agency that “A detailed review of prolactin in children… did not show a correlation between prolactin levels and adverse events that are potentially attributable to prolactin.”

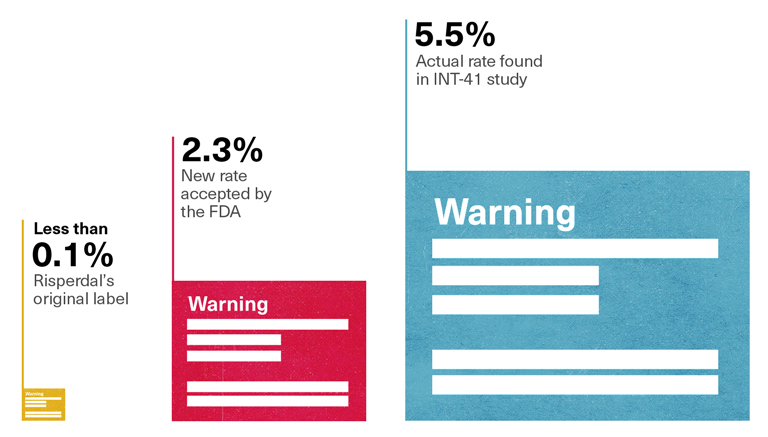

2.3 Percent, not 5.5 Percent

Tellingly, the rate of gynecomastia that the FDA safety reviewer, Dr. Alice Hughes, reported to her colleagues—and the rate that would be reported on the new label—was 2.3 percent. That was the percentage derived when the Janssen team had added up the results of 18 different studies of children taking Risperdal, most of which involved children using the drug for short periods of time. It was only when Risperdal had been taken for eight weeks or longer that gynecomastia seemed to develop, as evidenced by the 5.5 percent rate found in that study, conducted in 2000, called INT-41. Moreover, only the INT-41 study had paid what the study characterized as “special attention” to prolactin and its related side effects, meaning that that study alone had looked for what Vicki Starr had feared so many doctors would miss—that a patient’s apparent weight gain in his chest was about more than some extra pounds.

- FDA Safety Reviewer Gynecomastia ReportOct. 5, 2006 (p. 2)

- Final, Agreed-Upon LabelingOct. 5, 2006 (p. 24)

Mixing INT-41 with those other studies had watered down the rate—as had calculating the 2.3 percent rate of female breasts in males as a percentage of all children, instead of listing the higher percentage that would be derived by calculating the percentage among only the males in the studies. Yet the FDA had accepted Johnson & Johnson’s 2.3 percent claim.

Moreover, when it came to the relationship between elevated prolactin and gynecomastia, Johnson & Johnson apparently still hadn’t revealed to the agency the numbers for boys taking the drug for at least eight weeks that had been collected and turned into the table that had been prepared, then cast aside, for the study that became the Findling article. The result was the FDA reviewer’s statement that there was no correlation between elevated prolactin levels and potentially prolactin-related side effects, such as gynecomastia.

Put simply, there was no reading of the real numbers that could produce anything as low as a 2.3 percent rate, and no way to justify the definitive statement that there was no relationship between raised prolactin and gynecomastia.

Rate of Gynecomastia – Risperdal Label vs INT-41 Study

The FDA final review memorandum that was prepared to justify the new approval of Risperdal for children also reported that “a worldwide literature review, did not reveal any previously unreported serious adverse events likely to be causally associated with risperidone.” By this time, the Findling article had been published and, in fact, was being cited in other articles—exactly as the Excerpta Medica ghostwriters had promised their client.

However, in terms of all the litigation taking shape, the new label meant nothing. The legal storm brewing was about prior conduct—involving the information given to patients who had taken the drug well before 2006. A slightly expanded new label for 2006 onward wouldn’t help Johnson & Johnson’s defense in those cases.

If anything, the new label actually hurt J&J’s defense when it came to the litigation about breasts that Sheller was planning. True, the 2.3 percent rate of gynecomastia about to be listed on the label was fictitiously low. But it was 23 times higher than the risk described as “rare” on the pre-2006 label that Austin Pledger’s doctor and thousand of others had read. “Rare,” as listed on the pre-2006 label, meant one-tenth of 1 percent or less.

More important, all of the data that had yielded the new risk rate of 2.3% –flawed thought it was– had been available to Johnson & Johnson much earlier than 2006. So why hadn’t J&J warned Austin’s doctor and others then with a “Dear Doctor” letter and a change in the label?

Calming Patients, Not Treating Them

There was another memo in the FDA file about the new label application for treating children with autism that put in perspective the limits of the drug and the grudging risk-benefit analysis the agency was making. Its message, albeit in FDA-speak, was that Risperdal didn’t actually treat autism or any other illness. It was really a way to calm patients so that symptoms of autism could be controlled, which in the agency’s estimation was worth the high incidence of side effects the data they reviewed had demonstrated, such as somnolence (67 percent), appetite increase (49 percent) and fatigue (43 percent).

“There is no evidence that risperidone [Risperdal] treats the mental retardation or pervasive disruption of childhood development that are the core features of Autistic Disorder,” the memo from the FDA’s Dr. Paul Andreason conceded. “It is usually not the habit of the Division to approve drugs based on what might appear to be pseudo-specific effects of a drug on a disorder.

“However,”Andreason continued, “since there were no treatments for autism, the drug class was regularly used off-label for these symptoms, and there was little controlled trial data to support treatment for any part of autism, the Division decided to accept applications for the treatment of the irritability-like symptoms.”

That rationale might not have prevailed had the FDA known about the actual risk of gynecomastia. Or the label might have been approved, but with one of those black box warnings to highlight an especially high risk that doctors like Austin Pledger’s would have presumably have wanted to know about.

As revealing as these entries into the FDA’s Risperdal file might have been, the lawyers circling J&J had none of that information. Their initial courtroom attacks on the company would demonstrate just how out of the loop they were and how much more ammunition they still needed.