Showdown,

Almost

The 1-800 Cases Come to Philly

Aside from Gorsky’s deposition, Johnson & Johnson had still not had, or taken, the opportunity to offer its side of the story in any full-length, high profile adversarial hearing.

But in a Philadelphia courtroom in September 2012, that faceoff seemed imminent. Local judges had ordered all of the personal injury cases Sheller had gathered through his own office and through referrals—by now numbering over 200—to consolidate under one set of depositions, such as Gorsky’s, and one set of document demands. Then the individual cases were chosen for trial in the order in which they had been filed.

Both sides expected a few or maybe a dozen would be argued to a verdict. By then, each would be able to gauge the cases’ value in order to settle the rest. A loss or a lowball verdict in a few early cases would push the settlement in one direction; a few big wins would push the numbers the other way.

First up, on September 24, 2012, was Andrew Bentley of Houston. Then 17, Bentley had been prescribed Risperdal when he was 5 after being diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome . He started growing breasts at age 12.

Sheller was in court, but he was not the lawyer trying the case. By now 73, he had become convinced that he no longer could do jury trials himself, and he wasn’t sure that the other lawyers in his firm were as ready for a big-stakes brawl as some outside talent would be.

So Sheller lined up Bob Hilliard of Corpus Christi to try the cases. Among the referral deals Sheller had made was one with Hilliard, a charismatic litigator who had won headline verdicts in cases ranging from defective cars to formaldehyde in the FEMA trailers used to house Hurricane Katrina victims. Lately, Hilliard has been in the news as a lead lawyer in the General Motors faulty ignition switch cases.

Hilliard, in turn, had made a deal to get referrals from the Henry law firm, also in Corpus Christi, which ran those 1-800 ads seeking injury victims. It was the Henry ad recruiting Risperdal male breast victims that Benita Pledger had seen watching TV with her son that night in Alabama.

Austin Pledger’s case was among those Hilliard had brought to Sheller by way of the Henry brothers. Bentley was another, earlier Hilliard referral.

Sheller had agreed with Hilliard that Sheller’s firm would contribute all of the research and other background work they had been doing for the last eight years, plus the clients they had gathered on their own or through other referrals. Hilliard would bring the clients he had—and he would try all the cases in Philadelphia. The partners would split all expenses and winnings.

Risperdal Was ‘A Very Good Choice’

Outside the courtroom, on the day the Andrew Bentley trial opened, Sheller complained that the judge should reconsider a decision he had made not to force Gorsky to testify because the J&J lawyers said he had to be in Asia that week. The judge “was setting a terrible precedent because every corporate leader would suddenly find the need to be out of the country when subpoenaed by opposing counsel,” Sheller told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

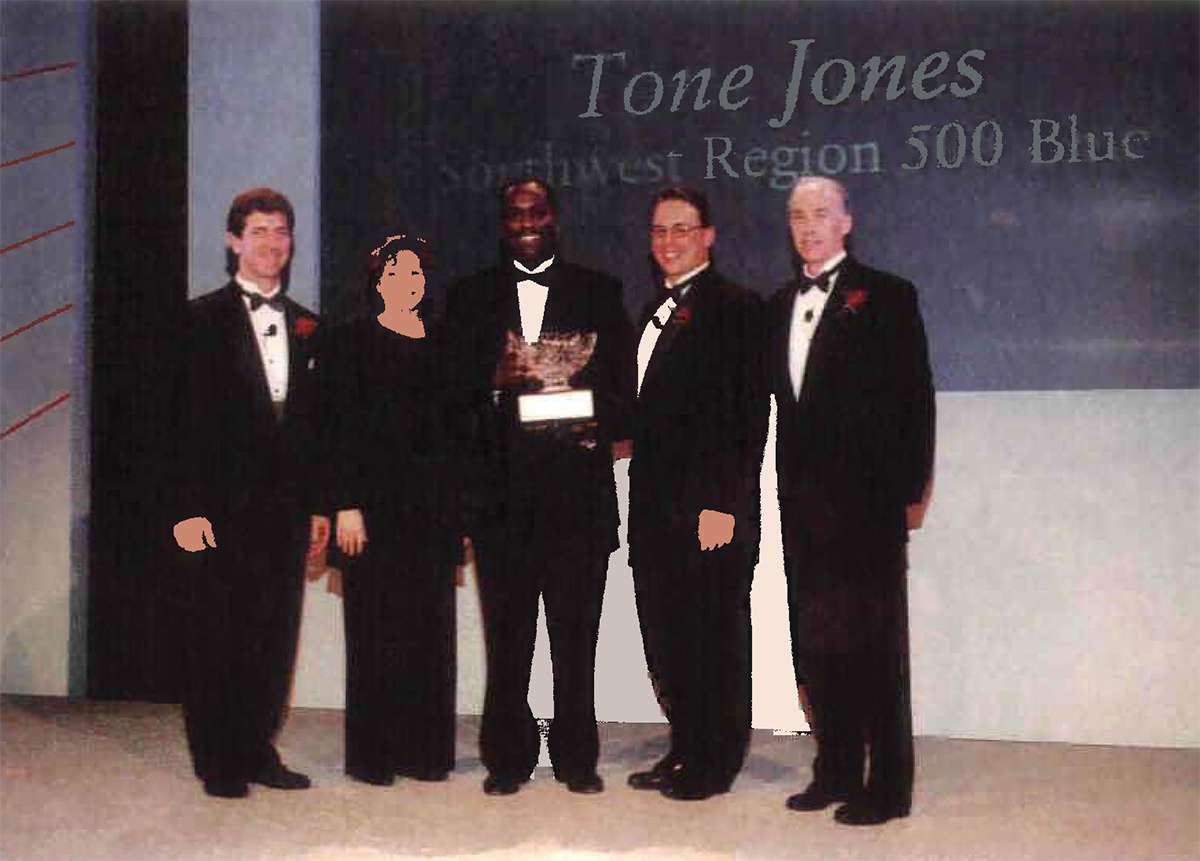

Gorsky or not, Hilliard opened the trial with a characteristic flourish, charging that although Risperdal was only approved to treat schizophrenia, Johnson & Johnson had decided that “schizophrenia in the United States did not meet the marketing requirements to make enough money for this drug.” His first witness was Tone Jones, a former Oklahoma State quarterback turned Risperdal salesman and sales manager in Texas. Jones described being pressured by the home office to sell Risperdal to pediatricians. He brought along Risperdal popcorn and a picture of Gorsky presiding over a ceremony giving Jones an award for exceeding his Risperdal sales targets.

Johnson & Johnson lawyer Laura Smith—a medical liability specialist, who had defended the company in its Arkansas case—assured the Philadelphia jury in her opening that Risperdal, which she called a “miracle drug,” had been knowledgeably used by the pediatrician who had prescribed it to Bentley. She said that if any salesperson had been caught actually trying to sell it to pediatricians, rather than just respond to their questions about the drug, he would have been fired.

Apparently, the Johnson & Johnson lawyers from headquarters watching the opening of the trial didn’t think Smith was winning over the jury. After the first week, they settled the case, along with four others scheduled to come next. Bentley was given what Sheller says was a “substantial sum; the client was very satisfied.”

Once again, J&J had sidestepped a fight.

“Our company policy was to promote Risperdal in its FDA indication,” a Johnson & Johnson spokeswoman told reporters. In a press release explaining the settlement, the company wrote*, “We take our obligation to ensure the safe and appropriate use of our medication very seriously.”

Soon, Johnson & Johnson’s lawyers began negotiations to settle other Sheller cases, including five more that had come to Sheller via Hilliard, and another 80 that he had gotten separately. Each case was negotiated, one by one.

By March 2014, all but five cases had been settled for what Sheller says were “very good amounts.”

The next case on the list to be evaluated for settlement was Austin Pledger’s.

Avoiding Paying for a Jury’s Outrage

But then the courts threw J&J a lifeline.

Looming over all of these suits in the company’s risk analysis was not simply a potential jury verdict for compensatory damages—the money, maybe two or three million dollars, that a boy and his family might get if Risperdal was proved to be the cause of his suffering. There was also the bigger question of punitive damages, the fine that juries can levy against a defendant for wrongdoing. It is supposed to be the jury’s way of punishing and deterring particularly bad conduct.

Compensatory damages are based, at least in theory, on some calculations of future medical costs and the value of the victim’s pain and suffering. Punitive damages are based on a jury’s sense of outrage. A jury whipped up in one of these Risperdal cases by an effective plaintiffs’ lawyer might levy millions, even tens of millions, more in punitive damages on top of compensatory damages. And that would bring on still more headlines, which would bring on still more hungry plaintiffs lawyers, with still more clients.

While one group of Johnson & Johnson lawyers were negotiating all of those settlements, another team had drafted a brief arguing that although the cases were being tried in Pennsylvania, a New Jersey statute banning punitive damages in cases of drugs approved by the FDA should apply because Janssen and Johnson & Johnson executives were based in New Jersey.

In May 2014, the judge ruled that there could be no punitive damages in the Risperdal cases.

Johnson & Johnson immediately abandoned its settlement posture. The company and its teams of lawyers geared up to fight the next case all the way to a verdict.

“As soon as punitives were off the table, Hilliard took his money and went home,” Sheller says. (Hilliard did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Hilliard then quickly settled a group of 1,200 cases he had collected in Texas for what was an undisclosed amount, but which Sheller says were “very small dollars for each case. … He wanted to wash his hands of the whole thing, and move on to General Motors.” If Hilliard got as little as $50,000 for each case, that would still have been quite a haul—$60 million—especially in Texas, where lawyers’ contingent fees are allowed to be as high as 40 percent.

Sheller suddenly had to scramble to find a new trial lawyer. By January 2015, he had made a new deal with Thomas Kline, another Philadelphia litigator, who, at 66, was nearly 10 years younger than Sheller.

“You know the expression, ‘dog with a bone?’” Kline asks. “Steve is kind of a one-bone dog.”

Kline’s website highlight reel includes multimillion dollar malpractice verdicts, suits against Penn State in the Jerry Sandusky sex scandal and mass torts brought against the manufacturers of Vioxx and the Dalkon Shield. That kind of work had netted him enough to be able to pledge $50 million to the law school of Drexel University, now named the Thomas R. Kline School of Law. (Sheller has given $1.5 million for a Center for Social Justice center in his and his wife’s name at Temple University Law School.)**

A smart dresser with wavy white hair, Kline is Sean Connery to Sheller’s Detective Columbo. His firm, with about 30 lawyers and a support staff of 100, is three times the size of Sheller’s.

With Sheller, you get the impression that he goes through life not believing how lucky he is to be making so much money for causes he believes in, or makes himself believe in. Kline may get wrapped up his cases, but he also seems to get a kick out of the business he’s in and think he deserves his success because he’s so good at it. “You know the expression, ‘dog with a bone?’” Kline asks. “Steve is kind of a one-bone dog.” He gets all tied up in causes, like Risperdal and prolactin. I tend to take a broader view.”

Kline told Sheller he would personally try the cases, as long as his new partner gave him, Kline says, “total control” of the litigation. But Sheller would still have to provide his new recruit with the firepower necessary to overcome what now promised to be Johnson & Johnson’s all-out defense.

Gathering Ammo

After Benita Pledger called that 1-800 number in 2011, she and her husband did not hear much beyond an occasional check in from the office of her lawyers in Texas. “My husband and I thought maybe it was some kind of scam,” she recalls.

Then, in 2013, she was asked to sign more forms. Soon, she got a call from a new lawyer—Christopher Gomez, one of Sheller’s partners.

Gomez explained that his firm was taking on her case in cooperation with the lawyers in Texas and arranged for her to fly to Philadelphia to begin preparing for trial. She would be the actual plaintiff, not Austin, because Austin was a year from his 21st birthday and was judged to be unable to handle his own affairs in any event.

Benita did not meet Kline, the lawyer who would actually argue the case in court and take her testimony, and she wouldn’t until just before the trial started. But she connected with Gomez, who told her about his own autistic child.

The case now appeared set to start in January 2015.

The Expert With The Golden Resume

As Kline prepared, Sheller gave him an encyclopedic report that he had commissioned in late 2012 that perfectly laid out the case. It was so complete and so compelling that it must have played a role in pushing J&J to settle those earlier cases when it was given to them as part of the pretrial discovery process (and while the threat of punitive damages had loomed). The author was David Kessler, an expert hired by Sheller at $1,000 an hour.

A Harvard-trained doctor with a law degree from the University of Chicago, Kessler had been a professor of pediatrics, epidemiology and biostatistics at, among other places, Yale, where he had also been dean of the medical school. To top that, he had also been commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration under presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton.

“I can’t defend Johnson & Johnson,” says Daneman. “What they did in withholding data was unconscionable.”

Sheller had asked Kessler to immerse himself in all the J&J documents and any other evidence the lawyers had accumulated about Risperdal and children. Then he was supposed to draw on his legal and medical training and his background as the nation’s top drug regulator to write a report detailing what it all amounted to.

The result was 111 dry but powerful pages laying out the facts in 386 numbered paragraphs.

Kessler is careful to point out that he is not a knee-jerk opponent of the drug industry—that he has been on the boards of two drug companies and that as FDA commissioner he led a drive to streamline the drug approval process, particularly drugs desperately needed at the time to control AIDS. “We approved more drugs during our tenure than at any other time in FDA history,” he says.

However, he recalls that as he pored through the material, “what I saw surprised even me, and I think I’ve seen everything.” He was, he says, “deeply troubled by how this company had done off-label marketing involving the most vulnerable of children.”

“These are some of the most powerful drugs imaginable,” Kessler adds. “I do not understand how one of the most respected companies—with its Credo—went so far astray.”

Line by line, Kessler took the reader—ultimately, the lawyers on both sides who would use the report to question Kessler at the upcoming trials—through the business plans and charts targeting the children’s market; the sales call reports documenting the pitches to pediatricians; the rationale behind the law prohibiting off-label sales (which quoted Senator Kefauver’s “the sky would be the limit” argument); the details, based on Priscilla Brandon’s discovery while sifting through all those documents one night in December 2009, of the trick they had played with the numerator and denominator in the data that formed the basis of the Findling article; his discovery of clinical studies showing gynecomastia rates in boys of 5.5 percent that had been mixed with other studies to camouflage the results; the Excerpta Media contract and its promise to produce friendly articles and place them in top academic journals; and the partnership with Harvard’s Dr. Biederman.

A J&J Author Backtracks

In late 2012, Sheller secured a weapon to supplement Kessler’s report. It came in the deposition taken by his partner, Christopher Gomez, of Denis Daneman, a Canadian doctor who had been a co-author of the Findling article. (Risperdal has never been approved for the treatment of children in Canada.)

Gomez walked Daneman through the various drafts of the article and pressed him on whether the denominator should have been lowered, which would have shown a higher percentage of gynecomastia cases. “That’s how I would do the analysis,” he conceded.

Gomez pressed him on why the data showing the relationship between elevated prolactin and gynecomastia had been left out and in fact was contradicted in the article’s abstract. “That’s the complete opposite of what we see in the draft, correct?”

“Correct,” Daneman conceded.

Should the statistically significant relationship between prolactin and gynecomastia after eight weeks of boys taking the drug have been mentioned in the 2003 article?

“Probably,” Danamen said.

At one point in the deposition, Danemen tried to assure Gomez that the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, where the article was published, has peer reviewers who vet everything for accuracy. Medical journals make much of their so-called peer review process when touting the their scholarly credibility.

Anna Kwapien, the publications manager at the journal, which is owned by the Memphis-based, for-profit Physicians Postgraduate Press. Inc., told me that the journal “never discloses who its peer reviewers are.”

Then how would one know the qualifications of the reviewers, or even that anyone did review an article, I asked, explaining that one such article had since been the subject of a dispute over its handling of data.

“We exist on trust,” she said. “Doctors know us.” She then referred me to two colleagues for further information. They did not return repeated calls.

Daneman, who is pediatrician-in-chief at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, told me that peer reviewers usually only see a draft of the article, not the underlying data.

‘Used and Abused’

Daneman also told me he was “surprised” by much of what the lawyers confronted him with at his deposition, including the misleading denominator. His involvement in the Findling article, he says, “was the most difficult thing in my career, and I’m 65 and ready to retire. … They never showed me that table [with the statistically significant relationship between prolactin levels and gynecomastia]. I felt used and abused by the entire process.”

Daneman says he donated what he recalls was “only a $1,000 fee” to charity, because “I want nothing to do with this.”

“I can’t defend Johnson & Johnson,” he adds. “There can be no debate about what they did. They crossed the line. What they did in withholding data was unconscionable.”

Daneman says that he never saw the final version of the article before it was published. It has, he says, since been quoted 121 times in other medical journals—something that “pains me.”

As for the article’s lead author and namesake, Robert Findling, a spokeswoman at Johns Hopkins, where Findling is now director of child and adolescent psychiatry, emailed me this statement from him: “At the time of manuscript submission, I was confident in the accuracy of the information provided and in the interpretation of the study results. However, in light of ongoing scrutiny of Risperdal, I became concerned about the questions raised and if there were errors. I am committed to determining what they may be and to correcting them. … [A] review is currently under way. Based on the findings, we will decide whether the paper warrants full retraction, a partial correction or whether the original findings stand.”

I sent a follow-up asking if the doctor had read every word of the first draft and the final article that bears his name. I received no reply.

During their hunt through documents turned over by Johnson & Johnson, lawyers at Sheller’s firm found an email describing Findling to a colleague from Carin Binder, the Janssen executive supervising clinical studies of Risperdal who had complained about the nauseating amount of side effects data in one draft of the Findling article. “He’ll do/say whatever you want him to” was Binder’s assessment, written in January 2003 (after the final version of the article bearing Findling’s name had been put to bed).

How Johnson & Johnson planned to defend the Findling article and its seeming manipulation of the gynecomastia data was the key question Sheller and Kline contemplated as they prepared for Austin Pledger’s trial.

*Correction: In the original version, we mistakenly called a press release a letter to investors.

**Correction: The piece misstated the names of the law schools that Thomas Kline and Stephen Sheller attended.