Firing Blanks, Hunting For

Smoking

Guns

A Weak First Case

On December 14, 2006, Stephen Sheller filed his first case against Johnson & Johnson. The client was a New Jersey boy who had taken Risperdal beginning in 2001. When he had met the boy and his mother, Sheller thought the case would be about diabetes and weight gain. But then she and her son became traumatized by his growing breasts, and in August 2004, he had radical surgery to remove them.

Still, the suit focused on diabetes, and the complaint Sheller wrote was a hodgepodge of weak claims, in large part because the boy had also taken the Risperdal competitor drug Seroquel. Its manufacturer, AstraZeneca, was also named as a defendant, as was the boy’s doctor, who was accused of malpractice.

The complaint claimed that Risperdal was the sole bad actor when it came to the boy’s breasts. Yet even in late 2006 Sheller knew so little that the charges he drafted did nothing more than show off that he had learned some new medical terms. There was nothing—no studies cited, no data—suggesting he had any proof that the drug actually caused gynecomastia, much less proof that Johnson & Johnson knew about a link and failed to warn doctors.

Battle Stations

Whatever the suit’s prospects, filing it gave Sheller a hunting license to demand all Risperdal documents related to the sale and marketing of the drug since 1994 and any tests that may have been conducted to determine its efficacy and safety.

At the same time he continued to spread the word among trial lawyer friends, looking for referrals. Sheller still wasn’t allowed to mention the qui tam false claims suit he had filed with Vicki Starr and with another J&J whistleblower whom he had since found to join her suit as a “relator.” But beating the drums to collect other patients claiming to have been injured by the drug was another matter.

Other cases were now springing up in Texas and California. And state attorneys general were jumping into the act, apparently preparing their own qui tam cases. Through 2007 and 2008, each quarterly financial disclosure Johnson & Johnson filed with the SEC brought news of more subpoenas from state prosecutors.

“You’d get a document demand and you’d go to work seeing what you had and how much you had to give up,” recalls one J&J lawyer. “You’d have someone subpoenaed to testify before a grand jury and you’d try to prepare him by anticipating what he might be asked. … And then you’d debrief the guy after the testimony. … But you really just had to sit and wait until they came to you to negotiate, which in this case took years.

“All the while, you’ve got the executives telling you, ‘We’ve gotta fight this thing. We didn’t do anything wrong, and, besides all the other guys [other drug companies] did just what we did.’”

Next is ‘God’

- Question:And what was it that bothered you so much? Is $2,500 a lot of money to you, or was it just that a deal is a deal?

- Dr. Biederman:A deal is a deal.

- Question:Is $2,500 a lot of money to you?

- Dr. Biederman:$2,500 is money.

- Question:Is it a lot of money?

- Dr. Biederman:I don’t know. Define “a lot.”

That exchange—between Dr. Joseph Biederman and a Houston plaintiffs lawyer whose firm had teamed up with Sheller in still more damage suits against Johnson & Johnson—was hardly the most combative or petty during one and a half days of a deposition that began on February 26, 2009. That morning, Biederman sat at a Boston law firm in front of five plaintiffs lawyers and six lawyers for the defense. In this instance, the verbal combat had to do with Biederman’s supposed fury over the late payment of a Johnson & Johnson speaker’s fee, a contretemps that had surfaced in emails that were among the millions of documents handed over to the plaintiffs. (Biederman denied that he ever gets “furious” because doing so would be “unprofessional.”)

Biederman had become a central figure in the Risperdal battles. Although little activity other than the filing of the personal injury complaints was public, the swirl of all the investigations and subpoenas had generated leaks and news coverage. Some of the worst headlines involved Biederman. Two years before, the Boston Globe had reported that a woman who had committed suicide had been taking Risperdal. The reporter found that it was Biederman who had prescribed the drug and that he had consulting contracts with Risperdal’s manufacturer.

The Globe story attracted the attention of staffers working for Sen. Charles Grassley, an Iowa Republican who had long been interested in conflicts of interest and other improprieties in the healthcare industry. Grassley wrote letters to Harvard, Mass General and Johnson & Johnson inquiring about Biederman’s financial relationship with the company, only to find out that the disclosure rules governing doctors associated with Harvard and Mass General basically amounted to an honor system. And when Grassley compared what J&J and other drug companies told him they had paid Biederman from 2000 through 2007 to what Harvard and Mass General told him Biederman had disclosed, he found, according to a speech he gave on the floor of the Senate on June 4, 2008, that Biederman had disclosed “a couple hundred thousand” but had actually received “over $1.6 million.”

Alerted to Grassley’s findings, the New York Times published a story outlining the discrepancies, noting that, “Dr. Biederman is one of the most influential researchers in child psychiatry and is widely admired for focusing the field’s attention on its most troubled young patients. Although many of his studies are small and often financed by drug makers, his work helped to fuel a controversial 40-fold increase from 1994 to 2003 in the diagnosis of pediatric bipolar disorder … and a rapid rise in the use of antipsychotic medicines in children.”

Five months later, in November 2008, the continuing fight by lawyers working for Johnson & Johnson and for Biederman (who were retained by Mass General) to keep him from having to testify at a deposition backfired. Papers filed by the plaintiffs lawyers to convince a judge to force his testimony contained a collection of juicy internal J&J documents related to Biederman’s relationship with the company—including the one recounting his fury at not having been paid that $3,000 speaking fee and the internal annual report from his J&J-financed center, acknowledging that one of its purposes was to further Johnson & Johnson’s business goals.

By the time Biederman—who declined repeated telephone and email requests for comment—appeared for his deposition three months later, in February 2009, the doctor had issued a statement attributing the gaps in his income disclosures that Grassley had identified to sloppy bookkeeping, and Harvard had said it had launched an investigation.

Asked about that in the deposition, Biederman said, “Senator Grassley claims to be interested in issues of conflict of interest and is interested in making sure that the universities have tight conflict-of-interest rules. I have no dispute with that.”

A former colleague of Harvard psychiatrist Joseph Biederman argues that he was “susceptible to being used by a drug company that set out to use him.”

That in turn led to the heart of why the lawyers wanted to question Biederman—and how they hoped to nail him: whether the center he had established with $2 million in J&J funds was meant to promote Risperdal to children using his, Harvard’s and Mass General’s imprimatur.

One barbed question referred to the emails that had begun with Alex Gorsky’s “money on the table” request to find ways to put J&J funds to work building revenue:

- Question:You never heard it in the context of your Center?

- Dr. Biederman:No. The Center did science only.

- Question:Well, the truth is the Center was just a marketing device for Janssen, right?

- Dr. Biederman:The Center was designed to advance the science of bipolar illness in children and ADHD across a large spectrum . This is what the Center did. … Janssen funded a center that was dedicated to the advancement of the science of the conditions for which they [Janssen] have effective treatments. …

- Question:So the truth is Janssen needed to make more money, they wanted to expand the pediatric market. They saw your center as a way to facilitate that, right?

- Dr. Biederman:I have no idea.

- Question:Do you think Janssen paid you millions of dollars to limit the use of Risperdal in kids?

- Dr. Biederman:Janssen funded a Center that was dedicated to the advancement of the science of the conditions for which they have effective treatments or potentially effective treatments.

- Question:I understand that’s your interpretation of Janssen’s intentions. However, having read this document that says we’re looking for “money on the table” … how can you interpret that any other way than to mean than Janssen was looking to you to help them develop this off-label marketing campaign?

- Dr. Biederman:I have no idea what is in the mind of Janssen executives.

Biederman had conceded earlier in the deposition that he had spent the prior day and a half with Janssen lawyers preparing these answers. But a former Mass General colleague argues, convincingly, that it would be unfair to convict him of anything other than believing in his science and wanting to use it to help the horrendously troubled children who paraded before him every day. Given that mindset, the former colleague argues, he was “susceptible to being used by a drug company that set out to use him.”

“This was not about money for Joe,” maintains this former colleague, who was not involved in Biederman’s work and who says he “really doesn’t care for Joe” personally. “The money was not life-changing for him, however the press made it out to be. … For Joe, it was all about his work, advancing it and being the most revered person in his field.”

True, Biederman brushed aside a question in the deposition about whether he knew that 20 percent of all Risperdal prescriptions were being written off-label for children: “I have no idea how much risperidone is used in children.”

And he dismissed the idea that he should consider himself responsible for “what Janssen did with your research”to promote widespread off-label use:“I don’t.”

However, to Biederman, this colleague insists, it really was about producing a best of both worlds scenario.

As Biederman put it, when asked another version of the basic question about his dealing with a profit-seeking drug company: “We proposed to advance science. I believed that advancing science … is doing the right thing and could result in profitability, too.”

The doctor was certainly self-assured enough to believe that he was doing nothing less than rescuing children. Near the beginning of his deposition, Biederman was asked to explain why he had noted on his resume the fact that he was the academic with the most citations—6,866—for scholarly articles related to ADD or ADHD (including many that praised Risperdal). “Because it’s an honor to have citations of this magnitude,” he answered.

He was then asked to explain the hierarchy at Harvard and his place in it. After Biederman had provided a tour up the academic ladder—from instructor, to assistant professor, to associate professor, to his title, full professor—the Texas plaintiffs lawyer asked him what came next.

Answer: “God.”

J&J’s Contribution to Obamacare

More than two years after Biederman’s testimony, Harvard would complete its investigation of his drug company income. The university issued a reprimand and required that he refrain from accepting fees of any kind from drug companies for one year, and get advance approval before engaging in any such paid activities for the following two years.

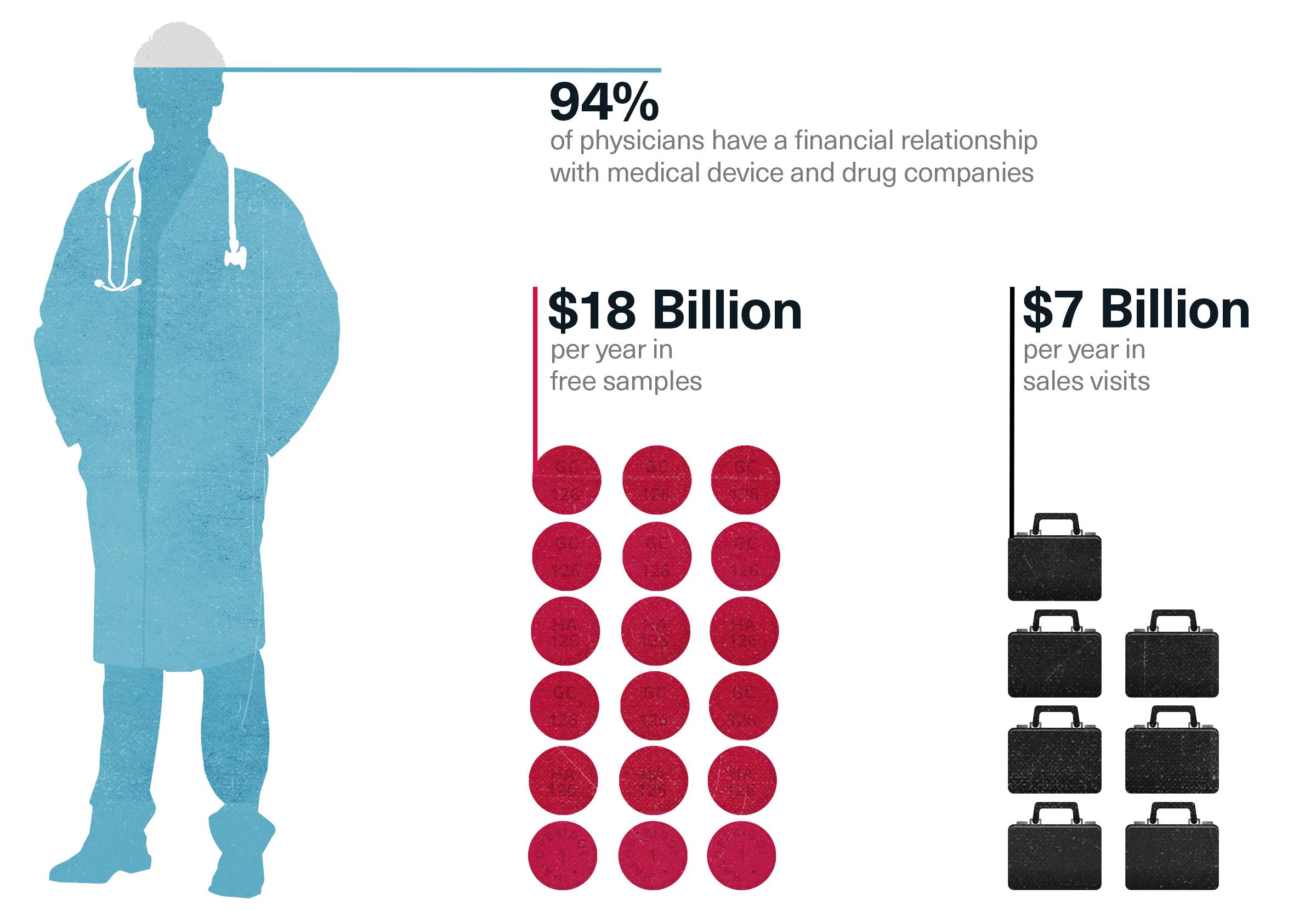

The publicity generated by Grassley’s investigation into the disclosures of drug company payments to Biederman sparked interest on Capitol Hill about such conflicts. After Grassley began his investigation, a Senate subcommittee heard testimony that drug and medical device companies had some kind of financial relationship—from providing free samples to paying consulting or speaking fees to financing research —with 94 percent of all practicing physicians, and that drug companies spent $7 billion a year on visits to physicians by salesmen, who provided the doctors with $18 billion worth of free samples.

The Coziness Quotient

As the senior Republican on the Finance Committee, Grassley was collaborating at the time with committee chairman Max Baucus, a Montana Democrat, on drafting what ultimately became Obamacare. Although he ultimately joined all of his Republican colleagues in opposing Obamacare, Grassley and his staff were instrumental in drafting provisions that remained part of the law when it was passed in 2010.

Grassley’s—and, indirectly, Biederman’s—contributions to Obamacare required full disclosure of financial relationships between drug companies and doctors, and provided for the Department of Health and Human Services to collect and post them on its website.

A Needle in a Haystack

Priscilla Brandon was in her 40s and working at a healthcare-related software company when she started attending law school at Widener University. Struggling to earn a living after graduating in 2006, she ended up as a lowest-on-the-totem-pole lawyer at Stephen Sheller’s firm, where she used her training as a programmer and analyst to do what was basically paralegal work—sifting through millions of digital documents. Precise and reserved, Brandon was the ultimate worker bee at a firm with eight other high-octane trial lawyers or lawyers who liked to think of themselves that way.

It is the Priscilla Brandons of the world who are on the receiving end when plaintiffs lawyers demand that the enemy turn over “any and all” documents related to a case, and then get what they ask for.

For Sheller’s personal injury cases, Johnson & Johnson turned over what Brandon calculates were 3.5 million documents containing 21.7 million individual pages.

That may have seemed like a burst of “here’s everything; we have nothing to hide” candor. But burying the opponent in documents hides the important needles in an impenetrable haystack.

Plaintiffs lawyers often grouse that this is deliberate obfuscation. Corporate defendants, of course, consider it fair play: If the plaintiffs lawyers are going to come after us because we have deep pockets and think they can score a fat contingent fee, no matter how real their case is, why not make them invest big money in staff time? Maybe they’ll settle quickly or just go away.

Sheller understands the game, although he doesn’t like it. “They keep trying to starve us into quitting,” is how he puts it, adding that “it also drives me crazy that other plaintiffs lawyers will come in by gobbling up clients online or with TV ads, and get settlements after we do all the work”—something which the corporate defense bar would no doubt dismiss as dishonor among thieves.

Fair or not, Brandon was Sheller’s go-to grinder when it came to dealing with the avalanche of Johnson & Johnson documents.

One night, three days before Christmas 2009, Brandon was going through some of the discovery documents J&J had delivered related to the personal injury cases Sheller had already filed. As with that first case brought in 2006 for the boy in New Jersey, Sheller’s injury claims were still mostly about diabetes. And they were looking increasingly unlikely to bring in big verdicts or settlements because of the difficulty of proving that while Risperdal caused weight gain—which the company had clearly warned about on its label—it also caused diabetes apart from weight gain.

Brandon had been asked by one of the lawyers working the cases to go back through all of the clinical studies J&J had turned over, each of which typically contained dozens of pages of text and tables attached to hundreds of pages of data. She was told to separate out the studies involving children and summarize them. It was a weeks-long project.

That night, on December 22, as Brandon continued sifting through the documents, she noticed one having to do with the drug’s long-term effects on children. It was called INT-41, and a description included in it noted that this study had paid “special attention” to prolactin levels and gynecomastia.

She remembered some emails she had seen referring to prolactin. And, of course, she knew that her boss had been trying to read everything he could about it, and that he had even filed one case—that first claim, in 2006—involving a boy who not only had diabetes but also breasts, for which he had undergone a double mastectomy. Sheller had already settled the case for relatively small dollars, because the charges were so muddled, and because he still had no proof about prolactin and breasts. Yet Brandon knew that her boss had continued to insist that there had to be a way to nail Johnson & Johnson for it.

Brandon found the emails about prolactin that she remembered. And attached to them she discovered the three drafts and final version of the Findling study—the one that had concluded that the data showed there was no relationship between breasts and raised prolactin levels.

She then began to compare the drafts side by side, sketching a set of columns to chart the different tables and conclusions that had appeared in each version.

It seemed that the authors had changed the tables, and when she compared the numbers, she saw that they had added one table that kept the same number of total participants in the denominator but, according to the text, removed all of the children aged 10 and over from the study. Looking further, she saw that they had changed the text to base their conclusions on that new table.

Brandon thought she might be on to something. She sent an email to the lawyer who had asked her to review the studies, explaining what she thought she might have found and attaching the documents that seemed to demonstrate it.

Within a few days, she and the other lawyers in the firm, piqued by the different numbers in the different drafts, had homed in on the internal emails documenting the machinations around the Findling article—including the ones about “re-analyzing” the data to “reassure” doctors who were being encouraged to prescribe Risperdal to children, and the one complaining about the “nauseating” data about side effects. The boss loved what his people brought him. “We had discovered what this case was all about and what these people had done,” Sheller later told me. “This wasn’t just selling off-label; it was knowing that the drug caused gynecomastia and covering that up.”

Beyond what that meant for his personal injury cases, Sheller thought that “the feds would love it” for their qui tam cases. “When I brought this to them,” he recalls, “it took a lot of explaining, but they got it.”