Chess, At

$1,000

An Hour

The New CEO

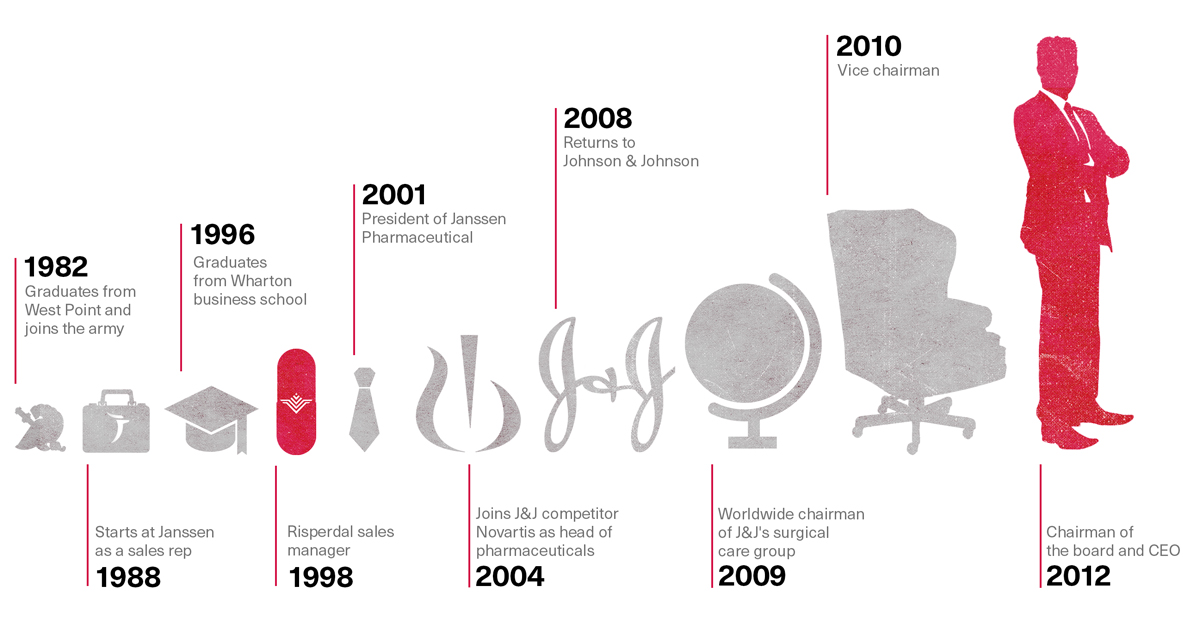

On February 21, 2012, five weeks after Johnson & Johnson paid $158 million to Texas and made Allen Jones a multimillionaire, the company announced that the board had appointed Alex Gorsky to succeed William Weldon as the new chief executive officer. The press release noted that Gorsky had begun at J&J in 1988 as a salesman for Janssen and then worked his way up to president of the unit. Although he had left in 2004 to run rival Novartis’ North American division, he had returned to the fold in 2008 to assume a variety of top positions, including vice chairman. The announcement quoted Weldon, the outgoing CEO, describing the “rigorous, thorough, and formal multi-year” board selection process.

I tried to reach each member of the J&J board that chose Gorsky to ask how Gorsky’s involvement in the Risperdal marketing and sales campaigns had factored into his or her decision. Of the 12—who include the former president of the University of Michigan and five retired Fortune 500 CEOs—I was able to reach eight by phone or email either directly or through their designated assistants. All declined comment on that question, and despite being independent board members, technically unaffiliated with the company, all referred me to J&J’s public relations department.

But Michael Johns, a board member, physician and former chancellor of Emory, did say, “As I understand it, Risperdal was a drug that treats symptoms of a disease, not any disease. So maybe it’s the system that’s screwed up.” That rationale aligns with how the company’s lawyers, according to one of them, saw the cases—that the government’s off-label argument puts the company in an impossible position when it comes to drugs like Risperdal. “These diseases,” the lawyer explained, “don’t have a blood test or anything else; they are all about symptoms. And many different types of people can have those symptoms, which our drug does a great job of alleviating.”

Gorsky was described in the Wall Street Journal story covering his promotion as a “former Army ranger, who had “edged out fellow Vice Chairman Sheri McCoy, 53, for the top spot. Both inside and outside the company,” the Journal reported, “Ms. McCoy was thought to have an edge over Mr. Gorsky in the horse race to become the 126-year-old company’s ninth leader.”

The story’s concluding sentence quoted a health industry consultant saying he “thinks the board chose Mr. Gorsky partly because ‘he has been responsible for the largest acquisition in the history of J&J,’ the Synthes deal.”

- J&J Synthes Press ReleaseApril 27, 2011

Synthes is a large manufacturer of surgical equipment and supplies whose $19.3 billion buy-out by Johnson & Johnson was announced in 2011. As Gorsky prepared to take over as CEO, the deal, which he had helped steer, was about to close.

For aficionados of illegal off-label sales, Synthes was a special company.

In 2009, a Pennsylvania-based subsidiary of Synthes was accused by federal prosecutors of illegally marketing and aiding in the misuse of “trauma products to treat damaged human bone” during surgery.

The subsidiary, called Norian, and Synthes itself, were charged with a total of 52 felonies and 44 misdemeanors, all involving an alleged conspiracy to encourage doctors to conduct unauthorized clinical trials of the company’s products on patients being treated for compression fractures of the spine, a painful condition suffered mostly by the elderly.

“Before the marketing program began,” federal prosecutors in Philadelphia alleged, “pilot studies showed the company that the bone cement reacted chemically with human blood in a test tube to cause blood clots. The research also showed, in a pig, that such … clots became lodged in the lungs.”

The company had not stopped marketing the product “until after a third patient had died on the operating table,” the government charged, adding that “after the death of the third patient in January 2004, Norian and Synthes did not recall the [bone cement] from the market—which would have required them to disclose details of the three deaths to the FDA. … Instead, the company compounded their crimes by carrying out a cover-up in which they lied to the FDA during an official inspection in May and June 2004.”

In short, according to the government, the new J&J acquisition had, prior to being acquired by J&J, illegally experimented on humans and killed three of them in the process, then lied to the FDA about it.

What would become known as the bone cement case would end up with four Norian executives pleading guilty and serving five to nine months in prison, and Synthes agreeing in 2010 to pay a $23 million fine.

As follow-on suits by patients or the heirs of dead patients then worked their way through the courts, the case became the subject of a riveting September 18, 2012 story in Fortune Magazine. The most telling item in Mina Kimes’ report might have been this: When Johnson & Johnson’s purchase of Synthes was announced a few months after the highly publicized guilty pleas and fines, the Johnson & Johnson press release, Kimes wrote, cited “Synthes’s ‘culture’ and ‘values’ as evidence of its appeal, even as former Synthes executives awaited sentencing on charges of grievous conduct.”

Tossing Gorsky a Hand Grenade

Alex Gorsky was scheduled to become Johnson & Johnson’s chief executive on April 26, 2012. Fifteen days before, an Arkansas judge ordered the company to pay $1.1 billion for illegal Risperdal marketing in his state. (The verdict would be thrown out two years later by the state Supreme Court, which ruled that the Arkansas false claims act did not apply to false statements about prescription drugs.)

But the Arkansas case wasn’t the J&J lawyers’ top concern that day. They were more worried, according to one company lawyer, about a brief that Boston federal prosecutors had just filed with a judge contesting the company’s refusal to make Alex Gorsky available for a deposition in its civil suit over the Risperdal/Omnicare nursing home case.

In March, the prosecutors handling the Omnicare case had sent Johnson & Johnson’s lawyers a letter matter-of-factly asking for dates when Gorsky could be deposed. The prosecutors knew that they were putting J&J and its new boss in a tight spot.

These kinds of chess plays are why lawyers on both sides of the highest stakes, white-collar litigation love the game.

Gorsky’s lawyers could make him available and expose him to a barrage of questions under oath about the Omnicare deal and about the alleged off-label promotion of Risperdal to the elderly. Or they could refuse to make him available by arguing that his testimony was not necessary; federal rules give corporations the right to refuse to make a top executive available if the judge believes the purpose of deposing him or her is harassment rather than a quest for real information. However, arguing that Gorsky testimony wasn’t relevant because he did not have direct knowledge opened the door for the government to go to the judge with a brief spelling out of why his testimony was relevant—in other words, all the details of his hands-on involvement.

These kinds of chess plays are why lawyers on both sides of the highest stakes, white collar litigation love the game. The prosecutors, who are typically lawyers with elite credentials, get to match moves with some of the most highly paid private-sector litigators anywhere. Like friends engaged in a fierce tennis match, there’s a collegiality binding both sides.

In fact, they often switch sides; by now, Michael Loucks, who had led the Boston office’s drug company investigations, had left to become a partner handling corporate securities fraud and white collar criminal defense in the Boston office of Skadden, Arps, one of the country’s top firms.

Gorsky and the J&J lawyers chose the lesser of the bad choices. “Mr. Gorsky had no reasonable connection to the subject matter of the Government’s complaint and was not involved in the facts underlying this case,” they wrote back on March 26, explaining why the new CEO shouldn’t have to sit for the deposition.

The government responded to this invitation to spell out Gorsky’s “reasonable connection” and his “involvement in the facts” underlying the charges that Omnicare had already settled. Its brief to the judge was not made part of the public record. But it was there for all the Johnson & Johnson lawyers, and their client, to read—a hand grenade whose pin could be pulled with a leak to the press, or, if it came to that, by cutting and pasting much of it into an amended suit naming the boss.

The Rise of Alex Gorsky

This was the first time any government document had tied Alex Gorsky to the Risperdal scandal. It did so in unrelenting detail, with each point followed by a reference to a document that the government had obtained through subpoenas to Johnson & Johnson and Janssen:

- “From October 1998 to October 2001, Mr. Gorsky was Janssen’s Vice President of Marketing, and from October 2001 to early 2003 he was President of Janssen.”

- “During all of that time he was responsible for selling Risperdal, a drug whose biggest customer was Omnicare.”

- “He regularly received Monthly Reports on J&J’s Long Term Care Group, including reports which commented on Omnicare’s efforts to promote prescribing of Risperdal and other J&J products.”

- “He met repeatedly with senior Omnicare executives to discuss those efforts.” (The meeting dates were then listed.)

As the government’s brief went on, the description of Gorsky’s involvement got more specific, as if the prosecutors meant to tighten the vise on the incoming CEO of the Credo company.

- “In advance of the May 1, 2000, meeting with Omnicare, for example, he received information that Risperdal’s 53.3% market share of Omnicare ‘represents Omnicare’s ability in persuading physicians to write Risperdal in the areas of Behavioral Disturbances associated with Dementia.’” (This was a quote from a document, referenced as an exhibit to the brief.)

- “As Vice President of Marketing and having previously worked closely with J&J’s Medical Development group (which was responsible for developing clinical trial data for Risperdal), he was in a position to know why J&J chose not to inform Omnicare (or members of Jansen’s own sales staff) that, in January 1999, the Food & Drug Administration (‘FDA’) had warned J&J that marketing Risperdal as safe and effective in the elderly would be false and misleading.”

- “Likewise, he was in a position to know why J&J did not disclose to Omnicare executives that, in 1999, the FDA had rejected J&J’s attempt to get approval to market Risperdal for treatment of psychotic and behavioral disturbances in dementia (by far the most prevalent use of Risperdal in Omnicare-served nursing facilities) because of inadequate safety data.”

- “Mr. Gorsky was also involved in approving payments [for data] to Omnicare under the 2000 Consulting and Services Agreement.”

In short, the reason Johnson & Johnson’s incoming CEO was needed to testify didn’t have to do with his current position. It was all about the positions he had held and been promoted from—the positions where he had demonstrated that he had the right stuff to lead the entire company, according to the board that had just anointed him. It was simply a matter of getting a company marketing manager, who happened to have become the CEO, to explain his conduct on the way up the ladder.

“We wanted to deal with everything at once,” recalls one Johnson & Johnson lawyer. “Just pay and be done with it all. And so did the government.”

It seemed like a strong argument. But the government actually didn’t care much about getting Gorsky’s deposition. This was all part of the chess game, which by the early half of 2012 was being played across a national map. Boston had its Risperdal/Omnicare investigation. And Philadelphia had its qui tam suits brought by Vicki Starr (and, by now, four others in a group Sheller was leading) involving the broader off-label marketing allegations. There was even a smaller-bore federal investigation in San Francisco related to the marketing of another Johnson & Johnson product, the heart failure drug Natrecor.

“We wanted to deal with everything at once,” recalls one Johnson & Johnson lawyer. “Just pay and be done with it all. And so did the government.”

For that reason, and because of the stakes and the big-name company involved, the Justice Department in Washington was now calling the shots. The man in charge was Tony West, who had been head of the Justice Department’s civil division, but had since been promoted to associate attorney general.

Although West had been a corporate lawyer in San Francisco, one line in his resume suggested that he was a bit more of a free spirit than other colleagues who rotate from corporate defense practices to the government and back again. In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, while working at his San Francisco firm, he had vigorously defended, pro bono, John Walker Lindh, the alleged “American Taliban,” who had been captured and tortured by American soldiers in Afghanistan. In fact, West’s work for Lindh, which included charging the Justice Department with a variety of abuses, had almost sidetracked his Senate confirmation when President Obama appointed him to the Justice Department in 2009.

“Tony was determined to make a mark with these drug cases,” says one defense lawyer. “He really projected a sense of disgust with the whole thing.”

West allowed the talks in Philadelphia to proceed. That was the place where the offenses likely to yield the most money (through the qui tam false claims) were being negotiated. But he kept close tabs on their progress and made it clear that he would be involved in the final deal.

Negotiations between the two sides in Philadelphia, which had begun in 2011, had proceeded into spring 2012 according to what had become something of a standard script. It was a script that had been followed in deals for off-label offenses that had been completed, with West signing off, in Philadelphia with Eli Lilly (in 2009), AstraZeneca (in 2010) and Novartis (also in 2010); and in Boston with Pfizer (in 2009) and Merck (in 2011). In fact, for the drug companies, it was sometimes the same lawyers representing different clients who were called in to lead the negotiations.

“We knew how this was going to be played,” recalls a defense lawyer who had been involved in one of those earlier deals and who was also involved in the J&J negotiations. “We also knew that these guys had a habit of wanting to raise the bar, so that if Lilly had paid $800 million and the guys they competed with in the Boston office had gotten $2.3 billion from Pfizer [although that involved allegations of four illegally marketed drugs], they were going to come after us hard.”

As was generally true in those cases, initially, the lawyers for the drug companies—one or two partners and a few lower-level associates each from as many as three different law firms hired by the company—would troop into a conference room at the prosecutor’s office and protest to Philadelphia U.S. Attorney Zane Memeger’s assistants that their client had done nothing wrong. The meeting might last an hour or two, during which the government would flash hints of its evidence and the defense lawyers would say something about how flimsy it all sounded.

The defense lawyers’ bills, at hourly rates of $400 to $1,000, totaled 7 to 12 thousand dollars an hour.

Sometimes Memeger would drop in to ask how things were going. It would all be friendly.

Memeger, an affable lawyer with a sterling resume, was part of the club. He had won awards as a government prosecutor before becoming a partner and white collar crime specialist at one of Philadelphia’s largest corporate firms. He had then been appointed U.S. attorney by Obama in 2010, allowing him to catch the tail end of the office’s high profile drug cases.

Months would go by as the government continued to examine documents and talk to witnesses, including some who would be put before a grand jury because this was proceeding as a criminal case, as well as a civil case potentially involving damages for false claims.

Then the defense lawyers would return and allow as how maybe some salespeople had gone off the reservation and done things they shouldn’t have done. The prosecutors would chuckle or feign outrage, and talk vaguely (or not so vaguely if the other side had managed to tempt them) about the evidence showing that higher-ups were involved and that this was all part of a company plan. Charlene Fullmer, one of the assistant U.S. Attorneys leading the investigation, would occasionally mention an especially bad piece of evidence, according to one lawyer. One of her favorites was the fact that an entire Risperdal ElderCare sales unit had been set up.

“There were innumerable meetings,” Memeger recalls. “They’d present. We’d present. Eventually, we would narrow the issues.”

Holding No One Responsible

Actually, the issues were only one issue: money.

Both sides had long since agreed in principle on a single misdemeanor criminal plea by the corporation—not by any individual.

The only question was how much all of this was going to cost Johnson & Johnson in civil damages and criminal fines.

Technically, the amount of the civil penalties was supposed to be calibrated to the amount of actual false claims—the amount paid by Medicare, veterans or others receiving federal health benefits resulting from the impermissible off-label selling. “We’d come in with economic analyses showing it was fifty or a hundred or two hundred million or whatever, but we knew they’d ignore that,” says one of the drug company negotiators. “They’d counter with three billion or something, maybe five. But they would never really tell us how they got there, because they had no idea. For them, it was easy.”

There was also the question of how the money would be split between a civil damages payment (for those false claims) and a criminal fine for the misdemeanor. In most situations civil payments are tax deductible; criminal fines are not. At a corporate tax rate of roughly 30 percent, that was a big difference; a lawyer who can move $100 million from the fine column to the civil column saves his client $30 million, making his $1,000 hourly rate negligible.

Meantime, according to another lawyer, the Johnson & Johnson executives, Gorsky included, were of two minds. They wanted to put this behind them, and the money, however off the charts by any rational standard, would not hurt the company’s financials too much or its standing on Wall Street. In fact, settling for almost any amount would help on Wall Street by resolving uncertainty. On the other hand, says this lawyer, “They were angry about the charges, because they thought they had a First Amendment right to sell products that they believed in, and they knew they were a good company.”

That single misdemeanor plea was also a standard part of the script. It was the deal all the big companies had made in their off-label cases, and, according to lawyers on both sides, nothing different was ever contemplated by either side in this case. This was despite the fact that the prosecutors in the negotiations with defense lawyers argued that the drug Johnson & Johnson sold was particularly powerful and that the off-label use was intended for the most vulnerable patients, the elderly and children.

‘What Can You Prove to a Jury?’

An individual is guilty of a misdemeanor, technically known as misbranding, if he or she causes an FDA-approved drug to be put into interstate commerce with the intention of having it be sold off-label. With all of the business plans and marketing campaigns targeted at children and the elderly that could be linked to Gorsky, that was something for which the prosecutors seemed to have convincing evidence.

The same offense is a felony if it is done with the intent to defraud. That’s a harder case to prove when it comes to the Janssen executives, such as Gorsky, although prosecutors might have been able to argue that this happened with the promotions to the elderly, especially through Omnicare, and with the company’s repeated efforts to get approval from the FDA to market to children at the same time that they were actually marketing to children.

“It’s really a matter of the quality of the evidence you have, and what you think you can prove to a jury,” Memeger told me, when asked about why no effort was made to name individuals.

“The statute of limitations also comes into play,” he added, referring to a federal criminal law that generally does not allow prosecutions to be initiated more than five years after the crime was allegedly committed. Had the government’s investigation not dragged out over so many years, that would not have been an issue, given that the prosecutors had begun their investigations in 2003 and the company’s allegedly illegal marketing had continued at least through 2004. And it would not have been an issue at all if the FDA had been monitoring the same prescription data that drug companies routinely purchase and if it had seen that within a year of Risperdal’s launch a high percentage of prescriptions were being written by doctors, such as pediatricians and those working at nursing homes, who treated patients in the prohibited markets.

However, as soon as the government and Johnson & Johnson began talks, the government asked that the company waive its statute of limitation protections for the corporation—in effect freezing the date for any criminal prosecution of the company as if it were occurring the day of the first discussions. Corporations almost always agree to the waiver, and J&J did in this case. Otherwise, the government lawyers told the J&J team, they might be forced to bring a criminal case immediately without considering all that the other side might offer in terms of countervailing evidence or settlement concessions. Waiving the statute of limitations for a corporation was also part of the dance that eased some of the rough edges off of the adversary process so that a deal could be struck.

As for the executives, “no lawyer is ever going to waive the statute for an individual,” Memeger explains. “The corporation, yes. But not for a person.”

Too Big to Nail

As with not holding any individual responsible, a misdemeanor plea for the corporation had also become almost automatic. This was true even if evidence proving intent to defraud was strong.

The government’s explanation for this is a variation on the “too big to jail” rationale used to explain why errant banks were treated leniently following the 2009 financial collapse. Under the law, any health care company convicted of, or pleading to, a felony is automatically disqualified from selling any of its products to Medicare. That could effectively put the company out of business, because Medicare is the country’s dominant health care buyer. Misdemeanors do not carry that penalty.

“These companies make hundreds of great products and have tens of thousands of people working for them,” is how one prosecutor put it. “Do you really want to shut them down and eliminate those products?”

Per the usual playbook, the company would plead to one misdemeanor. No individual executive would be charged.

In fact, you don’t have to. Under the same law, waivers of the disqualification provision are allowed so that Medicare can buy drugs or other products it needs, or so that the units of a company not involved in the wrongdoing can be walled off.

“Who wants to take a chance on a waiver?” was how one government lawyer responded when I raised that with him. “These companies would never agree to that.”

Vicki Starr Goes House-Hunting

By March 2012, according to lawyers on both sides, the prosecutors in Philadelphia and the Johnson & Johnson lawyers thought they had reached the broad outlines of a deal. J&J would pay fines and civil damages totaling about $1.3 billion. The numbers were still in flux and might go up or down a bit, but that was the target everyone was focused on.

And, per the usual playbook, the company would plead guilty to one misdemeanor.

No individual executive would be charged.

Ultimately the private qui tam lawyers led by Sheller had to approve any settlement, or their clients could withdraw and fight on. The discussions were now far enough long that the government lawyers thought it necessary at least to give their ostensible co-counsel the courtesy of sharing the $1.3 billion figure. The mix would be something like $300 million for the fine and $1 billion for the civil award under the False Claims Act.

“In April, I got the call,” Starr recalls. “The lawyers weren’t specific and said nothing was certain, but that I should think about being in a home in Washington [state] by the end of June.”

Starr started house-hunting. But then news began circulating in the financial press in May that the talks were, as the Wall Street Journal put it, “on hold.” The lawyers assured her, again, that nothing was certain but that the reason for the reported glitch was that the government wanted even more money. Everything seemed to be on track.

But, in fact, the process was becoming bogged down.

Memeger was not going to be allowed to close the deal by himself. Tony West had decided it was time to roll up all three prospective deals—the big case in Philadelphia, the not-as-big Omnicare case in Boston and the relatively small case in San Francisco—into one big deal. Besides, West didn’t think Memeger had been tough enough in negotiating his piece. In fact, he wanted the sum of each of the three pieces to be larger than their parts.

“What happened was that ultimately our friends at Main Justice stepped in and wanted more money for a global resolution,” explains Memeger, referring to his bosses in Washington.

According to one lawyer involved in the bargaining, West (who is now general counsel of PepsiCo and would not discuss any aspect of his work in his old job) wanted $3 billion to make all of J&J’s troubles go away.

The talks were moved mostly to a conference room at Department of Justice headquarters, where the same routine of seemingly endless back and forth presentations would start to play out.

It now looked like Vicki Starr might have plenty of time to get used to her new home before she realized any tax savings from it.

There was, however, one development, in spring 2012, that was a surprise: Starr’s former boss, Alex Gorsky, was about to be forced to testify under oath about how he had marketed Risperdal.

‘I Don’t Remember the Specific Exercise’

“I may remember from time to time during the course of the year [that] their management may provide the opportunity for additional investment in different areas of the business that was called a ‘money on the table’ exercise. But I don’t remember the specific exercise.”

That was how Alex Gorsky answered a question about the “money on the table” reference in his email that precipitated the decision by his company to fund Dr. Joseph Biederman’s Center for Children and Adolescent Bi-Polar Disorders.

His reference to “their management” was, of course, a reference to himself. At Janssen during that time, he was management.

On May 26, 2012, Gorsky, supported by four lawyers, was forced to sit for a deposition at the Philadelphia office of one of Johnson & Johnson’s law firms. But this was not the session that had been demanded by the government. Federal prosecutors had suspended that fight while they tried to iron out a settlement.

Instead, his questioner was a lawyer in Sheller’s firm. The deposition was carried out in advance of the personal injury cases Sheller had brought on behalf of boys with gynecomastia, which were scheduled to begin later in 2012. This was Gorsky’s opportunity to tell his and Johnson & Johnson’s side of the story and explain all of those seemingly damning internal documents.

Most of his answers were similar to what he had to say about “money on the table.” He either only vaguely remembered, or didn’t remember at all. For example:

His favorite adjective was “appropriate.” For example:

- Question:[About the FDA’s warning that marketing Risperdal as safe andeffective in the elderly was “false and misleading”] Do you agree with that statement, Mr. Gorsky?

- Gorsky:I think throughout the time we felt that we were promoting Risperdal in an appropriate manner based upon the label at the time.

- Question:Well, if Johnson & Johnson marketed Risperdal to the children and adolescent market when Risperdal was not approved for a pediatric use by the FDA, would that be illegal?

- Gorsky:Based on my knowledge and my review of the information, I don’t believe that we—that is, Johnson & Johnson or Janssen—marketed the product in an inappropriate manner.

- Question:If Johnson & Johnson promoted Risperdal to the children and adolescent market when it was not approved for any pediatric use by the FDA, would you consider that a breach of the Johnson & Johnson Credo?

- Gorsky:I would consider inappropriate promotion of our products not consistent with the Johnson & Johnson Credo. But I’m not aware, other than very unique or specific situations that can occur in a large organization, I’m not aware of any concerted effort on the part of Janssen or Johnson & Johnson to promote the drug inappropriately.

- Question:Mr. Gorsky, did Janssen or Johnson & Johnson market or promote Risperdal to the child and adolescent market before Risperdal was approved or indicated by the FDA for pediatric use?

- Gorsky:Based upon my recollection and the documents I’ve seen, we promoted it in an appropriate manner.

According to Gorsky, the various business plans he had been in charge of were not what they appeared to be. For example:

- Question:[Referring to one of the internal Janssen business plans] The next sentence says, “Although the RISPERDAL Base business is rooted in the Schizophrenia marketplace, another fast-growing portion of this market is in children and adolescents.” Did I read that right?

- Gorsky:Yes, you did.

- Question:And because of the growth of the child and adolescent antipsychotic market … did Johnson & Johnson begin to approach this market in a different way in or around 2001?

- Gorsky:Not that I’m aware of, other than we were continuing to pursue the clinical development program of the product in that area.

- Question:Turn to the top of the next page, please. … Down below it says, “RISPERDAL use in the child/adolescent population is exploding.” But in this time frame, 2001/2002, Risperdal is not indicated by the FDA for any pediatric use, is it?

- Gorsky:Again, we did not have the specific indication, as we discussed earlier, until 2006. I don’t remember exactly what the labeling said regarding use in children, but as I discussed earlier, there was a significant—there appeared to be a significant increase in the recognition of this condition in children and adolescents during this time … which was substantiated by data and its occurrence. And physicians have an opportunity to use a treatment that they perceive to be appropriate and effective in a particular patient population, and that’s clearly what we were seeing happening in this area.

- Question:Look down at the heading that says “Key Base Business Goals and Objectives.” Do you see that?

- Gorsky:Yes.

- Question:And the fifth of the Key Base Business Goals says, “Grow and protect share in child/adolescents.” Is that right?

- Gorsky:Yes, that’s correct.

- Question:My question is, how can Johnson & Johnson grow a share in a child and adolescent market when the drug isn’t even indicated for use in the child and adolescent market?

- Gorsky:Well, my interpretation of that is, this is in fact a marketing plan, not a selling plan. As a marketing plan, its intent is to cover a wide range of activities regarding the development as well as the promotion of Risperdal. That being said, all of our actual promotion to the physicians would follow what was outlined in our package insert and all of our materials went through a significant review process, and that’s the way our representatives were trained. And in an area such as this, this is a marketer versus a sales representative, their language.

It added up to an effective tap dance that must have made his lawyers proud. But Gorsky’s testimony was not nearly as important to his company as finishing the deal with federal prosecutors.