It didn’t take long for them to find her. Soon after Michele Dauber started teaching at Stanford Law School in the fall of 2001, a few female students came to her office and told her they had been sexually assaulted. After a time, she came to expect that if she kept her door open, especially in the first three months of the school year, a girl she had never met would come in, crying. “I know before she’s made it all the way through the door what she’s going to say,” Dauber said.

Dauber, now 53, is small and intense, with a wavy mop of graying hair. She seemed to understand the students’ distress in a way that other professors didn’t. She fought for the students in Stanford’s byzantine system; then, when recourse failed to come, she fought to change the system. The students in her class on college sexual assault, many of whom were themselves survivors, seemed “in awe” of her, a friend told me. Once, Dauber even let a student who no longer felt safe on campus live for a while in her Palo Alto home, along with her family, four chickens and a rescued cat. And then, on January 18, 2015, a friend of Dauber’s own daughter was assaulted—by a 19-year-old Stanford student named Brock Turner.

Before Donald Trump bragged on tape about grabbing women by the pussy, before the Harvey Weinstein stories unleashed a national reckoning over sexual assault, there was the Brock Turner case—a lurid, unforgettable embodiment of campus rape culture. The young woman passed out behind a dumpster near a Stanford fraternity. The young man, a potential Olympic swimmer, thrusting on top of her. The two Swedish students riding past who saw him and gave chase. The trial in which Turner’s father lamented that his son’s life was being destroyed over “20 minutes of action.”

But what seared the case into public memory was the victim’s statement to the court at Turner’s sentencing hearing. “You don’t know me, but you’ve been inside me, and that’s why we’re here today,” she began. The then-22-year-old, known as Emily Doe, recounted waking up in the hospital and learning that she had been found with her underwear off and her dress hiked up to her waist, dirt and pine needles in her vagina. She described, in excruciating detail, the effect of the assault and the trial. “You took away my worth, my privacy, my energy, my time, my safety, my intimacy, my confidence, my own voice, until today,” she wrote. Turner had informed the court he hoped to educate other young people that “one decision has the potential to change your entire life.” Emily’s response was devastating: “A life, one life, yours, you forgot about mine.”

After BuzzFeed published the entire 7,200-word statement, it was shared 11 million times in four days. CNN’s Ashleigh Banfield took the first half of her show to read it aloud, stopping to calm her quavering voice. Nineteen members of Congress, Republican and Democrat, read it on the floor of the House. Emily Doe was sitting in her pajamas eating cantaloupe when she learned that Vice President Joe Biden had written her a heartfelt open letter. She got messages of support from as far away as Botswana and India. The statement, Dauber said, “was the manifesto of the Me Too movement. This was a harbinger.”

Michele Dauber reminds her assistant of a military bulldozer called the D9. “It can go through a mountain or a house or through everything and it doesn’t stop even when missiles are shot at it,” the assistant explained. JEFF CHIU/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Michele Dauber reminds her assistant of a military bulldozer called the D9. “It can go through a mountain or a house or through everything and it doesn’t stop even when missiles are shot at it,” the assistant explained. JEFF CHIU/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Emily and one of Dauber’s daughters had been “inseparable” friends in middle and high school, according to a letter Dauber wrote to the court. The two slept over at each other’s houses; Emily joined the family on vacation. Dauber described her as a “lovely, warm, talented, funny girl.”

At Turner’s June 2016 sentencing, Dauber sat with Emily. There was one case before Turner’s—that of a man named Ming Hsuan Chiang, who had been accused by his former fiancée of brutal domestic violence. “The photos of her that she showed in court looked like CSI: Miami,” Dauber recalled.

In a plea deal that Chiang’s lawyer had negotiated with the district attorney’s office, Chiang pleaded no contest to a charge of battery causing serious bodily harm. The deal entailed a sentence of 72 days in county jail, which was accepted by the judge, Aaron Persky. But because California’s jails are overcrowded, a progressive measure gives convicts one day off per day served for good behavior, effectively halving sentences. That meant Chiang would spend only 36 days in jail. In addition, the deal allowed him to serve his time on weekends, so Chiang wouldn’t lose his job as a software engineer in Silicon Valley. Pending good behavior, Persky indicated he would also consider downgrading the felony to a misdemeanor, so that Chiang wouldn’t lose his work visa. Even though the woman had ultimately agreed to the deal, in court she had protested the very idea that her assailant was able to negotiate a more favorable sentence for himself. “When I get beaten, can I ask for a better offer?” she said, her voice breaking. “Can I ask for a ‘discount’ beating?”

Dauber and Emily watched this unfold in horror. “The whole courtroom grinds to a halt,” Dauber recalled. “Can the clerk stop what she’s doing and call down to the jail and find out what time Mr. Batterer is going to get to work on Monday? I mean, it was surreal.” By the time Turner’s case came up and Emily stood to read her soon-to-be-viral statement, Dauber felt in her gut that the same thing was about to happen to her.

“Emily Doe’s statement was the manifesto of the Me Too movement,” Dauber said. “This was a harbinger.”The investigation and trial had shown that Turner and Emily met at a frat party, where they were both drinking. But while Emily’s memory goes black early in the evening, Turner claimed she had agreed to go back to his room. On the way there, he said, they slipped on the path behind the dumpster and started kissing. When the police found them, Emily was unconscious and partly naked. Turner’s pants were still on, but the rape kit showed that he had digitally penetrated her. Turner admitted this, but claimed that Emily Doe had consented before passing out, which Emily vehemently denied—she was so deeply unconscious that she did not revive for hours after she was taken to the hospital.

The jury sided with Emily. In March 2016, Turner was convicted on all three felony charges, including assault with intent to commit rape and penetration of an unconscious person. Under California law, he could have served a maximum of 14 years in state prison, but the district attorney had asked for six. Instead, Persky sentenced Turner to just six months in county jail—which would be only three months under the same measure that had applied in Chiang’s case. Persky also sentenced Turner to three years of probation and ordered him to register as a sex offender. Since Turner’s felony convictions made him ineligible for probation, Persky had to read into the record why he felt Turner deserved an exemption. When the judge cited the “severe impact” that a prison sentence would have on a young person without a criminal record, Dauber was dumbfounded. “There was no moment in the case in which he said to Turner, ‘Young man, you are being sentenced because you have done a bad thing,’” Dauber told me. “Instead there’s this incredible solicitude.”

After what she had witnessed, Dauber was convinced that Persky needed to go. As an elected judge, he could be voted out, but the next primary was five days after Turner was sentenced. Persky was running unopposed and the filing date to challenge him had passed. Dauber couldn’t bear the thought of all the other Emily Does that Persky might brush aside before the next election in six years. And since California is one of eight states that allows judges to be recalled by popular vote, she decided to launch a campaign to have him removed from the bench. There have been only two successful judicial recalls in California’s history, the last one in 1932.

“Since you are going to disrobe Persky, I am going to treat you like ‘Emily Doe,’” wrote the person who sent Dauber a letter containing white powder.Over the next year and a half, Dauber raised more than $1 million from over 5,000 donors, most of whom contributed less than $100. She mobilized scores of volunteers and won endorsements from local politicians, unions and prominent feminists, including Kirsten Gillibrand, Lena Dunham and Anita Hill. This January, having accumulated nearly 95,000 signatures, Dauber got the recall on the ballot in Santa Clara County for the June 5 election.

The Me Too movement has supercharged Dauber’s campaign. But it has also fueled the opposition to her effort—joined by much of the state’s legal establishment—and created a deep hostility toward Dauber and her tactics. On February 14, a letter arrived at Dauber’s Stanford office. The message inside read, “Since you are going to disrobe Persky, I am going to treat you like ‘Emily Doe.’ Let’s see what kind of sentencing I get for being a rich white male.” A white powder fell from the envelope.

Dauber froze. “This can’t be happening,” she thought as Stanford evacuated part of the building. The powder turned out to be harmless, but the episode shook her deeply. These days, she mostly works from home. She has plastered her office door at Stanford with printouts of the rape and death threats that she regularly receives. On a recent spring afternoon, Dauber was wearing a gray T-shirt that said “UNFORTUNATELY FOR HIM, HE RAN INTO SOME VERY STRONG WOMEN,” but she wasn’t feeling as confident. “It was naïve of me to think that we could do something like this, that directly challenges so many powerful institutions, and not encounter an intense backlash,” she admitted. Her crusade against Persky had turned into something far uglier and far more personal than she had ever imagined.

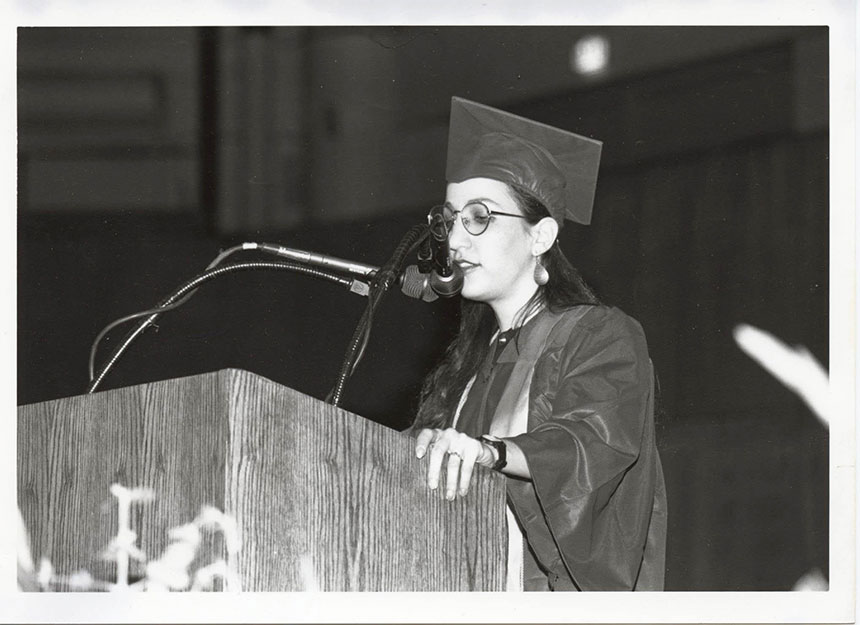

The site of Emily Doe's assault. ROBIN ABCARIAN/LA TIMES/GETTY

The site of Emily Doe's assault. ROBIN ABCARIAN/LA TIMES/GETTY

“He’s going to be home for the Labor Day barbecue with Mom and Dad,” Dauber said for about the tenth time. It was September 1, 2016, the day before Brock Turner’s release, and Dauber had planned a protest for the next morning in front of the Santa Clara County jail. We were sitting in her office at the Stanford Law School, where Dauber was simultaneously talking to me and her two teaching assistants, fielding media calls and proudly showing off a matching tattoo she had just gotten with a young feminist ally. “Yup. I like it. It’s a really good quote. Really good. Devastating. Yup. Good strong quote. OK. Thanks. Byeeee,” she said into her phone. On hearing that the recall campaign had just been endorsed by Democratic Senate candidate Loretta Sanchez, Dauber reacted with an expletive that, under her “no swearing” ground rules, I could not reproduce. She considered my pen frozen above my notepad and relented. “You can just say, ‘Amazeballs!’”

I had reached out to Dauber in the summer of 2016, when her campaign had just started. She agreed to talk, although she had an evolving set of additional rules. I was not to report on her children. She would not talk about her personal life. She would not talk about Emily Doe, their relationship or how Emily was faring. She also refused under any circumstances to pass along a message to her. Even considering an interview request would be too upsetting, Dauber explained.

To describe Dauber as intense would be an understatement. She speaks rapidly and at length; our interviews regularly stretched past the four-hour mark. She would call me at all hours and glut my phone with endless text messages. She is frenetic and frazzled and funny and winningly open—unusual qualities for a seasoned political activist who is well-connected among Palo Alto’s tech elite. (Her husband, Ken, is an engineer at Google and sits on the local school board.) At the time Dauber launched the recall, she was also serving on Hillary Clinton’s finance committee and would become an active fundraiser and bundler for the campaign. At the 2016 Democratic convention, I watched her pitch feminist attendees on the Persky recall with the force of an industrial fire hose. When California representative Jackie Speier stopped to say hello, Dauber was momentarily overcome. “She said I’m powerful!” she shouted to me over the din of a hotel lobby. “Which is amazing because she is such a badass, you have no idea!”

Judge Persky is “very interested in what will work for the abuser and it’s really to the exclusion of the victim. As far as I can tell, he doesn’t see her,” Dauber said.To get the recall on the ballot, Dauber needed nearly 60,000 signatures—representing 20 percent of the votes cast in the last election for that seat. She was hiring professional signature gatherers, at a cost of around $5 a signature. Major donors to the operation included the founder of LinkedIn and the daughter of the co-founder of Intel. Joe Trippi, the veteran Democratic operative, offered some of his California-based communications staff as volunteers. “She has this ability to persuade people to help her,” observed her friend, the author Jon Krakauer, who said he too has gotten “sucked in.”

Dauber didn’t want her efforts to be dismissed as some obscure local matter, so she assembled a coalition that reached far beyond Santa Clara. Feminist Majority, a national advocacy organization, committed to raise $100,000. GRLCVLT, a feminist secret society on Facebook, hosted a Brooklyn fundraiser featuring indie bands and powerful speeches from the actresses Amber Tamblyn and Rose McGowan, along with merchandise like little clutches resembling female genitalia, down to the strategically placed brass knob. At the event, Dauber immersed herself in earnest conversations with young women—“I’ve become, like, a feminist icon to them,” she explained—and was buttonholed by an intense McGowan for a good portion of the evening.

Scenes from the fundraiser hosted by GRLCVLT in Brooklyn. TWITTER

Scenes from the fundraiser hosted by GRLCVLT in Brooklyn. TWITTER

To convince voters that Persky was unfit for the bench, Dauber knew she needed to demonstrate that Turner’s sentence was not an isolated bad decision. Her teaching assistant, a graduate student named Emma Tsurkov, was also working on the recall. Dauber asked her to dig into the previous 18 months in which Persky had been hearing criminal cases. Tsurkov found some cases that appalled them both. In 2015, Ikaika Gunderson, an aspiring 21-year-old football player, had beaten and choked his girlfriend, then pushed her out of a parked car. Gunderson pleaded no contest to a felony count of domestic violence. Persky agreed to delay Gunderson’s sentencing for a year so he could attend school at the University of Hawaii and try out for the football team, provided he took a domestic violence class and attended weekly AA meetings. Robert Chain had been caught with child pornography, including an image of an infant being penetrated. Chain had expressed remorse and pleaded guilty. He got off with time served: two days in jail. In 2016, Keenan Smith, a football player at the College of San Mateo, was convicted of domestic violence after hitting his girlfriend and punching a bystander who tried to defend her. After he pleaded guilty to misdemeanors as part of a plea deal, he was sentenced to 120 days in a weekend work program.

To Dauber, it was evidence of a damning pattern. “He’s very interested in what will work for the abuser and it’s really to the exclusion of the victim,” she said. “As far as I can tell, he doesn’t see her.”

Seeking to unleash a barrage of damning stories—“like, boom, boom, boom”— Dauber passed Tsurkov’s findings at strategic intervals to The Guardian, BuzzFeed and The Mercury News, which all published articles that aligned with Dauber’s conclusions. Tsurkov, who once served in a combat engineering unit in the Israeli army, compared her boss to a military bulldozer called the D9. “It can go through a mountain or a house or through everything and it doesn’t stop even when missiles are shot at it,” Tsurkov explained. “She sometimes reminds me of that.”

By the time Dauber’s rally got going in front of the Santa Clara County jail in downtown San Jose on September 2, 2016, Turner was already en route to his family’s home in Ohio. (“He’s not my problem,” Dauber had told me that morning. “I’m not protesting him.”) Flanked by Sanchez, survivors, activists and a dozen state and national politicians, Dauber addressed the crowd of about 100 protesters and the assembled media with a calm but forceful conviction. Often, when she speaks, it is almost impossible to imagine a counterargument.

I asked John Smith why he was exposing Emily Doe’s identity. “She’s a prop,” he said.And yet, despite Dauber’s rigorous preparations, the event didn’t go as smoothly as she’d hoped. An activist with “STILL NOT ASKING FOR IT” scrawled on her bare chest in red lipstick kept threatening to get into the shot of Dauber’s CNN interview. At another point, an older man I'll call John Smith was spotted in the crowd. Smith had somehow figured out Emily Doe’s identity, even though Persky had ordered it to be redacted from the court records. He had been posting her real name on social media for several weeks. Dauber said she had enlisted her Silicon Valley connections to try and scrub the name from various websites. But now Smith was standing in full view of the cameras, holding up a dry-erase board with the victim’s name scrawled on it for everyone to see.

Dauber quietly moved toward Smith and pounced. She grabbed the board and took off running toward the police. When they refused to intervene, Dauber became frantic. She had worked so hard to protect Emily's privacy. Dauber erased the name with her sleeve and gave his board to the police. Smith spent the rest of the rally getting in loud skirmishes with various women and complaining that Dauber was “weaponizing” rape. I asked him why he was so intent on exposing Emily’s identity. “She’s a prop,” Smith said, recording me with his flip cam.

When it was all over, Dauber sank onto a concrete ledge under a tree, convinced that she had ruined everything. “I’m afraid that he’s going to, like, post some viral video of me erasing her name off his board,” she said in a fast, pressured stream. “I had, like, a full-bore panic attack. I mean, I can’t violate his free speech, I’m not the state, so it doesn’t matter. But I also probably didn’t have the right to touch his board.”

She stopped and looked at me.

“Does it make me look crazy?” she pleaded.

Then another problem occurred to her. “This isn’t helping to talk to a reporter about this,” she muttered.

“Ugh, God,” she groaned. “I’m probably just going to throw up now.”

Brock Turner leaves the Santa Clara County jail after serving three months. STEPHEN LAM/REUTERS

Brock Turner leaves the Santa Clara County jail after serving three months. STEPHEN LAM/REUTERS

Dauber may be a hero to many Stanford students, but when I visited the campus in April, I discovered that much of the faculty does not feel the same way. Twenty-nine Stanford Law professors have signed a letter against the recall. Robert Weisberg, who teaches criminal law and describes himself as a progressive feminist, grew visibly angry when he spoke about Dauber. The recall, he argued, was “a gratuitous and vindictive campaign” and “an exploitation of the Me Too movement.”

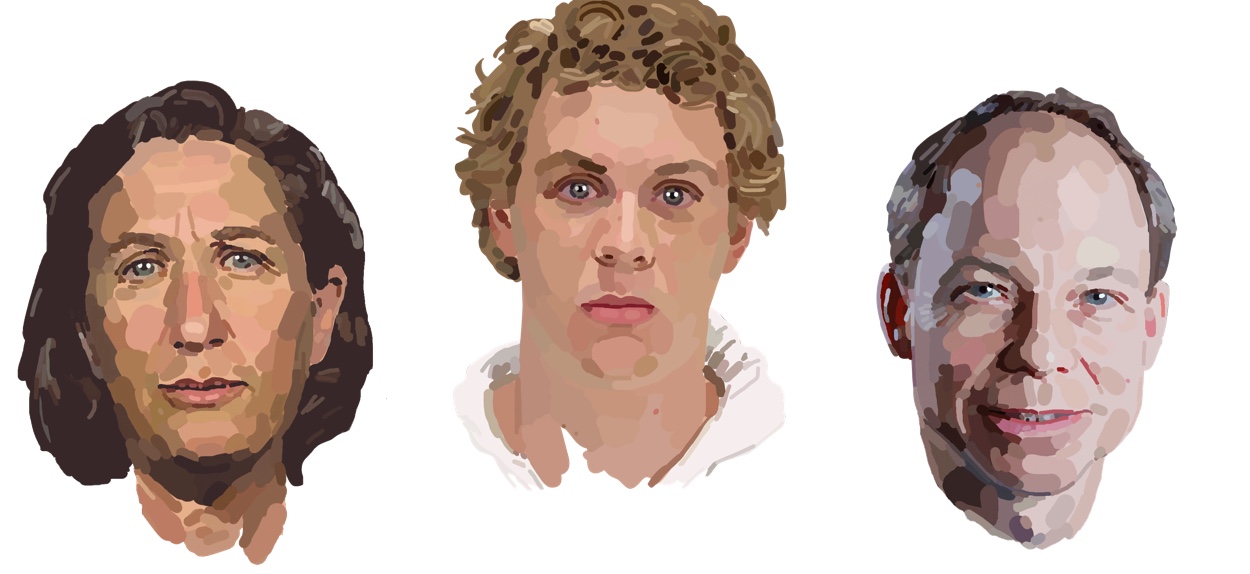

“You can’t not respect [Dauber], whether you agree with her or not. And you better come prepared if you’re going to disagree with her.”Dauber has always been an outsider at Stanford. She grew up in Pennsylvania and Indiana, and ran away from home under circumstances she adamantly refuses to discuss. Nor will she say much about having her first daughter, Amanda, at 17; being temporarily homeless; getting a GED and then a college degree in social work while battling drug and alcohol addiction; and being married to an abusive man with whom she had two more kids. “I wasn’t as good of a student as I wanted to be, I wasn’t as good of a parent as I wanted to be,” she told me. “I had to make compromises in every area.” And yet living in a poor neighborhood in Chicago made her acutely aware that she had “benefited from white privilege”—educated parents and a house full of books. She eventually left her first husband and has been sober for 29 years.

Dauber didn’t deny that she has experienced sexual assault but didn’t want to say more. “It’s not even an interesting fact,” she told me curtly. “I don’t think that this is the reason I’m doing [the recall]. Quite frankly, if every college professor who is a survivor stood up for this, we wouldn’t be where we are.”

After college, Dauber wanted to get a law degree. At the time, she was bringing up three kids, relying on welfare. She was accepted by Northwestern’s law school, as well as its sociology department for a Ph.D. When she discovered that she would receive a stipend, she told me, it “was the happiest day of my life.”

In law school, Dauber stood out for her “shredding intellect,” said her friend Russlynn Ali. “She was sophisticated. She was unique. She had children. A life that would cripple most people, she had overcome with grace.” Ali added: “You can’t not respect her, whether you agree with her or not. And you better come prepared if you’re going to disagree with her.” While at Northwestern, Michele met Ken Dauber, a divorced father of one, whom she married in 1997.

Dauber giving a commencement speech at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1993. COURTESY OF MICHELE DAUBER

Dauber giving a commencement speech at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1993. COURTESY OF MICHELE DAUBER

One summer, Dauber took a job at a corporate law firm in Washington, D.C., hoping to earn enough money to buy a used minivan. It was 1996, the height of Newt Gingrich’s effort to gut the welfare state, and Dauber was still on food stamps. The gulf between her and her affluent colleagues was “this vertigo experience,” she recalled. When President Bill Clinton signed welfare reform into law, Dauber took some cardboard from the office trash and furiously scribbled SHAME on it in black marker. She said she marched down to the White House expecting to join a big protest, only to find that she was protesting alone. After deciding that the corporate life was not for her, she lobbied hard to clerk for Judge Stephen Reinhardt, a progressive icon on California’s U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit.

Reinhardt died in March, but I spoke to him last year about Dauber, with whom he had remained close. “No one who’s met Michele can forget her,” he told me. “She was always very concerned about sex inequality, force and violence.” During her clerkship in 1998, she helped to raise money to fund scholarships for students doing public-interest law. “She was very aggressive, and got all the clerks to contribute—even the ones who didn’t agree with her,” Reinhardt recalled, affectionately describing her as a “tigress.” He had mixed feelings about the recall, but told me he admired Dauber’s pursuit of what she felt was right, no matter whom she alienated: “Michele is never going to take the middle path.”

In 2001, Dauber, who had just given birth again, was hired by Stanford Law School—a development that seemed nothing short of miraculous to her. The family settled into a craftsman house in Palo Alto. Ken went to work at Google. Dauber finished her dissertation, which would become an acclaimed book on the history of U.S. government disaster relief. In 2007, she got tenure. Then, the next year, her daughter Amanda died by suicide.

Dauber reeled. For a time, she went to work as a wilderness ranger at Yosemite. “It was a way to get her bearings,” said Krakauer. In the following years, she also spent time with Emily Doe. “Emily and her daughter were in the same herd, as she put it, and she was their den mother,” Krakauer said. (Later, Dauber and her husband would occasionally discuss Amanda’s death in the press after launching a campaign to raise awareness of teen suicides in Palo Alto’s highly competitive schools.)

After she returned to work, Dauber began to advocate more forcefully for victims of sexual assault. The university’s procedures had long disturbed her. Offenses had to be proved beyond the reasonable doubt standard of a court of law. Students could be cross-examined by the person who assaulted them. In 2009, securely tenured, Dauber wrote to the vice provost calling for policy change.

Two years later, she became co-chair of Stanford’s Board on Judicial Affairs, which oversees the process of disciplining students. As a first step, she started collecting statistics. Stanford only adopted standardized disciplinary procedures for sexual assault in 1997. By 2009, Dauber said, the university had received reports of 175 forcible rapes on its campus. Of those incidents that involved identifiable students, only four resulted in hearings, which in turn resulted in just two findings of responsibility and only one expulsion. (Stanford disputes Dauber’s methodology.) “It was the most subversive thing you could do: gather data and put it out there,” Dauber said. “You can’t get that toothpaste back in the tube.”

Dauber’s committee worked with the provost’s office in its years-long revision of the rules. The new process included lowering the burden of proof to a “preponderance of evidence” and providing for an investigator who reported back to a trained five-person panel. The accuser and accused never had to be in the room together. According to Dauber, adjudications shot up under the new rules—but findings of responsibility did not increase proportionally. In 2014, the panel found that a Stanford student had committed an “unwanted sexual act” against a senior named Leah Francis. But the punishment was a five-quarter suspension, to begin after graduation. The student would be allowed to return for graduate school, after effectively taking a year off. With Dauber’s help, Francis sought his expulsion. When Stanford rejected their appeal, Dauber publicly critized the decision. “I really couldn’t be more disappointed,” she told The Mercury News.

The episode frayed the trust that had existed between Dauber and Stanford. She wasn’t the only faculty member to criticize the decision, “but she was the one working with the provost,” said Shelley Correll, Dauber’s ally and the director of Stanford’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research. “Her criticism probably felt relentless.” Said Dauber: “All hell broke loose in my career.”

Stanford formed another sexual assault task force, this time without Dauber, and rolled back many reforms she had advocated for. Now, a three-person panel had to unanimously find a student responsible of wrongdoing. This time, Dauber vented to The New York Times. “The victim should not need to garner three votes to win while the respondent needs to garner only one,” she said.

ELIJAH NOUVELAGE/REUTERS

ELIJAH NOUVELAGE/REUTERS

Stanford, Dauber told me during one Christmas vacation, “is one of the most unfriendly, if not the most unfriendly school to victims of sexual assault.” She was waving off her husband, who was urging her to get off the phone and go skiing with the family. Stanford is “at the bright center of the universe today,” she went on. "And we think that because we’re good at engineering, we’re good at everything.” (A Stanford representative said in a statement, “We do not know on what basis she is making these comparisons. We strongly encourage victims of sexual harassment and sexual violence to come forward, so they can receive support and care and so that the university can investigate and adjudicate their cases.”)

The recall, a Stanford professor argued, was “a gratuitous and vindictive campaign” and “an exploitation of the Me Too movement.”I asked literature professor David Palumbo-Liu, one of Dauber’s few faculty allies, if she is really such a black sheep at the university. “At the moment, that’s probably accurate,” he replied.

Still, because she is tenured, Dauber can’t be fired. I pointed out to her that there was a certain irony in the fact that she, unlike Persky, is insulated from political pressure to do difficult, perhaps unpopular things. Dauber dismissed the comparison. The system allows judicial recalls, so why not use that tool? “He is a judge who self-evidently does not have tenure,” she said. “The question isn’t, ‘Couldn’t we select our judge another way?’ The question is, ‘How do we select them in California?’”

GABRIELLE LURIE/AFP/GETTY

GABRIELLE LURIE/AFP/GETTY

After the Labor Day rally, I went to the Santa Clara County Superior Court, Room 89—the same courtroom where Turner had been sentenced and where Persky was still presiding. As it happened, Turner’s last day in jail was also Persky’s last day on the criminal bench. In an effort to tamp down the controversy, the judge asked to be reassigned from hearing criminal cases, though this did nothing to satisfy his critics, since many sexual assault cases end up in civil court.

The last defendants on his docket were two young Hispanic women awaiting sentencing on nonviolent drug charges. The bailiffs, the court reporter, the clerk, and the public defender were gossiping about Turner’s journey to the airport shortly after dawn (“they’re treating him like O.J. Simpson, helicopters following his car”) and my presence in the courtroom. (“She has her computer out.” “Clearly high profile.” “Get her out of here.”)

Eventually, Persky emerged, looking wan in his black robe. He raced through the women’s cases, handing them over to supervised release rather than prison. “Don’t use drugs,” he admonished them softly. As he left, one of the women called out, “Have a good last day, Mr. Persky!” Surprised, he turned his head and murmured, “Thank you. Good luck.”

Persky was a more popular figure in the Santa Clara courthouse than his public image would suggest, for reasons that the women’s public defender, Gary Goodman, was eager to explain in the hallway. Goodman, a fervent Persky supporter, had donated $250 to the judge’s defense effort. “He has high integrity, he follows the law,” Goodman insisted. “You won’t find a lawyer who has been in front of him and says that he hasn’t been treated with respect and fairness.”

The Persky whom Goodman knows is a registered Democrat and a lifelong liberal. A few years older than Dauber, he grew up in San Francisco. His father was a psychiatrist, his mother a French teacher. He went to Stanford, where he captained the lacrosse team and wrote music columns for the college paper, and then to law school at Berkeley. In 1997, he joined the district attorney’s office, where he prosecuted sex crimes and juvenile offenders. He ran for a seat on the Santa Clara County Superior Court in 2002, on a platform of criminal justice reform. He lost, but was appointed to fill a vacancy the following year.

Most judges are former prosecutors, inclined to hand down the tough sentences they once sought as lawyers. But despite Persky’s six years in the district attorney’s office, as a judge he has seemed almost constitutionally averse to locking people up. “My clients are all indigent and most of them are nonwhite,” said Barbara Muller, a public defender in Santa Clara County who has appeared before Persky several times. “I have never seen him treat my clients differently than those clients who can afford private attorneys.” A Bay Area judge who was not authorized to speak to the press said, “He gives light sentences. Generally, the problem is the sentences are too heavy.”

Goodman felt that Dauber had knowingly distorted the facts of the Turner case and Persky’s record on the bench. When sentencing Turner to six months, Persky was accepting the probation department’s recommendation, as he has done in every trial, according to a review by The Associated Press. When he considered the damage a prison term would do to Turner, Persky had been following California sentencing guidelines, which allow lenience for youthful or elderly defendants with no significant criminal record. The state’s prison overcrowding crisis also generally motivates judges to seek alternative punishments and minimal incarceration for new offenders. “He’s a 19-year-old with no criminal record. It should be very hard to send them to jail,” Goodman said. Many Persky supporters also dispute the premise that Turner was let off lightly, since he will have to register as a sex offender for the rest of his life. “If this were my client, I’d say take prison over sex offender registration,” Goodman told me.

An anti-recall rally in February 2018. PAUL CHIN/THE CHRONICLE

An anti-recall rally in February 2018. PAUL CHIN/THE CHRONICLE

In December 2016, the Commission on Judicial Performance cleared Persky of any wrongdoing. Its report stated that a “comparison to other cases handled by Judge Persky that were publicly identified does not support a finding of bias.” Dauber’s critics in the California legal community have pointed out that four cases are not evidence of a pattern. Moreover, where Dauber sees Persky favoring male defendents, they see a judge rubber-stamping plea deals struck between the district attorney and the accused—a standard procedure in which the judge has little agency. “The system in California is very DA-driven,” says Ellen Kreitzberg, a former public defender who teaches law at Santa Clara University and who opposes the recall. “They decide how to charge the defendant, they decide the plea deal. The judge can decide not to take the plea deal but it very rarely happens. The judge is secondary. Every case that Michele Dauber cites is a plea bargain, except for Brock Turner’s.”

Kreitzberg also said that it was not unusual for a judge to take steps to prevent a convict from losing a job (as in the Chiang case) or a chance of a career (as in the cases of Gunderson or Keenan Smith). In fact, she argued, this should be the desired approach. Often, Kreitzberg explained, California judges find themselves grappling with the question: “How do we hold this person accountable without losing them forever to the criminal justice system? It’s in the victims’ interests to make sure they never offend again.”

Even Jeff Rosen, the Santa Clara district attorney whose office prosecuted Turner and who was “outraged” by the sentence, told me he did not consider it out of bounds. “It was a lawful sentence, and there was no legal basis to appeal it,” said Rosen, who has become an outspoken voice against the recall. “Most of the judges in the state of California would’ve done the same.”

For all of these reasons, Goodman saw Persky as the second victim in the case, after Emily Doe, with Dauber playing the second aggressor, after Brock Turner. “She’s a bully,” he nearly spat. “She’s ruined a man’s reputation based on things that are factually inaccurate.”

As we were talking, Persky walked past, now just a man in slacks and a crisp shirt. I called out to ask if we could set up a time to speak.

“He’s not allowed to talk to you,” Goodman said, as Persky smiled, tipped his straw hat and disappeared down the sunny hallway.

Removing a judge from the bench has been controversial ever since Western states adopted recalls during the Progressive Era. In 1911, President Howard Taft vetoed Arizona’s entry into the Union specifically because the territory allowed the practice. Judicial recalls, he wrote in his veto message, were “likely to subject the rights of the individual to the possible tyranny of a popular majority.” He also called them “legalized terrorism.” Populists like William Jennings Bryan, meanwhile, countered that they offered a way to wrestle back power from the special interests.

Today, Dauber echoes the progressives and the populists, while against her stands nearly the entire California legal establishment. The Santa Clara County Bar Association, a group of retired judicial officers from Santa Clara County, the California Judges Association, 90 California law professors and more than 400 public defenders and attorneys publicly came out against the recall. These opponents take different positions on Turner’s sentence, but all warn that removing Persky would set a dangerous precedent.

“One of my greatest concerns is that we’ll create a system where judges will be worried about getting bounced out by people raising a lot of money,” said one legal scholar. “And that’s inherently not progressive.” The Bay Area judge—who believed Persky “made a mistake” and that Turner should have received a two-year prison term—told me emphatically that the threat of a recall doesn’t “leave room for judges to do what’s unpopular.” Rosen, the district attorney, agreed: “I don’t want judges holding their finger up to the wind and making the decision based upon what public sentiment is.”

“Our prisons are full of poor black and brown people who did way less terrible things than Brock Turner and never got even a fraction of the solicitude shown to him,” Dauber said.In particular, the recall’s critics believe that judges may feel pressured to hand down harsher punishments to avoid a backlash. They referred me to a 2015 Brennan Center for Justice study showing that judges give longer sentences in the period before judicial elections. Already, Rosen and others told me, some local judges had come to fear “getting Perskied.”

In September 2016, California Governor Jerry Brown signed two bills inspired by the Turner case and written by Rosen’s office. They expand the legal definition of rape and make the sexual assault of an unconscious person punishable by a mandatory minimum of three years. Among both legal experts and sexual assault advocates, the bills were divisive—and not along predictable lines. Some questioned the introduction of a new mandatory minimum in a state that has been trying to wind back mass incarceration for years, arguing that this law will disproportionately affect poor people and minorities. "When we broaden those criminal definitions, it can broaden the swath of persons that can be criminalized," said Emily Austin, director of advocacy for the California Coalition Against Sexual Assault.

The law’s proponents, however, argued that there was a fundamental difference between mandatory sentences for, say, nonviolent drug offenses, and those for sexual assault. The criminal justice system has failed to take sexual crimes seriously for decades—and they are uniquely difficult cases to try, given the challenges of proving that a sexual act was nonconsensual. A recent study found that for every 100 rapes, only one perpetrator will get prison time.

As for Dauber, she responds to the critiques of her position like a trained lawyer: prepared, forceful, no concessions. “It’s really disorienting to me to see people who portray themselves as advocates against mass incarceration and for the equal treatment of minority defendants arguing for probation for a white, privileged athlete at the most elite school in America who was convicted by a jury of three serious felonies and served no time in prison,” she said. “Our prisons are full of poor black and brown people who did way less terrible things than Brock Turner and never got even a fraction of the solicitude shown to him.” She herself had refused to endorse the new mandatory minimum law. “It doesn’t solve the problem of one bad judge by tying the hands of a thousand good judges,” she told me. “Better to get rid of the one bad judge.”

Dauber believes that in some essential way, Persky misunderstands his role. “I think he sees himself almost like a social worker, you know?” she says. “Like his job is to rehabilitate these people. Rehabilitation is an important goal of punishment, but I don’t think that what he’s doing is the right way. Because without accountability and consequences, I think your chances for rehabilitation, particularly for sex offenses, is lower. I think there has to be both.”

Given the enormous stakes, I wondered how Emily Doe felt about the very public fight that Dauber was waging to get justice for her. While Dauber was neither her parent nor her attorney, she portrayed herself as the sole gatekeeper to Emily Doe. She still refused to pass along an interview request because she said it would be too traumatic for Emily, although the recall had kept the details of the assault in the local media on a regular basis. I felt that I was obligated to give Emily, an adult, an opportunity to respond if she chose to, out of basic journalistic fairness. I had seen Emily’s real name on John Smith’s board and was able to find her email address. During my visit in September 2016, I decided to let Dauber know that I wanted to contact Emily without publicly revealing her identity.

I knocked on Dauber’s office door. From inside, she said she couldn’t talk right now. But as I turned to go, she came out, quickly closing the door behind her. She looked nervous and on edge.

“What do you want?” she barked.

When I explained my intentions, Dauber grew irate. Absolutely not, she said. There was no option I could present that would pacify her, nothing, that is, except swearing to her then and there that I wouldn’t attempt to contact Emily in any way. The more I tried to explain my reasoning, the angrier Dauber became. I would have to accept Dauber’s “no comment” on Emily’s behalf. My tape recorder wasn’t running and I wasn’t taking notes, but Dauber caught herself. “This conversation is off the record,” she said and ducked back into her office, shutting the door.

By the next morning, Dauber had come around to the idea of my sending questions to Emily through the district attorney’s office. But she also informed me that due to her concerns about my ethics, the profile was off.

On November 15, 2016, exactly one week after Donald Trump was elected president despite being accused of sexual assault by a dozen women, Glamour magazine presented a Women of the Year award to Emily Doe. The actresses Gabourey Sidibe, Freida Pinto and Amber Heard read her court statement on stage. Emily herself watched from home, while Dauber collected the award and delivered her speech on her behalf. “Thank you for seeing me through my words and giving me a voice without having to see me physically,” she said.

Dauber was in bad shape after Clinton’s defeat. “I cried out loud,” she recalled. “Like, public, ugly crying for, like, a week.” She threw herself into the recall with renewed zeal. The following fall, the revelation of Harvey Weinstein’s long history of sexual predation triggered a wave of high-profile firings and resignations. Suddenly, Dauber’s local ballot initiative was part of a national attempt to figure out how to deal with the perpetrators and enablers of rape culture.

By this point, Dauber was talking to me again. In December 2017, I had reached out to her volunteer press secretary and was surprised to get a reply from Dauber herself. Her den mother instincts had kicked into overdrive when she heard that I had gotten Emily’s name from John Smith’s board and that I wanted to contact her over her objections. She denied that she had been angry, just upset. She said she found it “troubling” that I “obtained the victim's name from someone who attempted to publicize the victim's identity.”

When I flew out to see her in April, it was clear that her campaign had become grueling. Endorsements from Democratic politicians and luminaries were no longer falling in her lap. One night, I watched her corner Jeff Bleich, a Democratic candidate for California lieutenant governor, at a meeting of local Democratic activists. Dauber had wanted his endorsement because he was the former president of the California bar association—a useful foil to the phalanx of lawyers and judges aligned against her. But Bleich was nonsensically noncommittal, offering to endorse the recall, but only privately. He explained that he hadn’t had a chance to fully study the complex issues involved. “I don’t have time for three-hour conversations. It’s a factually intense case that you’ve made,” he said, squirming and eyeing the door, which was blocked by Dauber’s diminutive figure.

Dauber would not budge. For every objection he raised, she had an implacable multi-point rebuttal. I recognized the vise he was in—and the way he seemed to relent out of exhaustion just to extricate himself from the conversation. Before he was out of earshot, Dauber was gleefully planning to tout the endorsement on social media, until one of her volunteers talked her into a more subtle approach.

As we drove back to Palo Alto, Dauber kept turning over something Bleich had said. “I know a lot of people who know victims of abuse, who know the system is bullshit,” he’d said. “They think [the perpetrators] should all go to jail for three to five years and experience everything that people of lower socio-economic classes experience, but for them this is about Aaron Persky.” It was all just guild loyalty, Dauber concluded in disgust: lawyers who didn’t want to offend the judges they might one day have to face in court.

Boxes in Dauber's home containing the petition to recall Persky. TWITTER

Boxes in Dauber's home containing the petition to recall Persky. TWITTER

The recall fight had turned extremely nasty, the intensity more typical of a national campaign. Dauber was distributing an article reporting that Persky’s side had hired a political consultant who worked for Trump in Arizona. Dauber’s opponents passed me information that she was working with a woman who had been a partner at the firm that had produced the Willie Horton ad.

“I can’t prove it, but I think Dauber wrote the victim letter,” Cordell said.Improbably, this war was raging inside one of the most liberal communities in the nation—Hillary Clinton carried the county by over 50 points—among people who probably agreed with each other most of the time. The leaders of the opposition were largely women, including women of color. They were law professors, public defenders, respected opponents of the death penalty, criminal justice reformers, former judges, pioneering feminists and even survivors of sexual assault, many of whom believed the system was broken for victims. And they were incensed at Dauber for implying that recall opponents weren’t serious about rape. “This is a progressive family fight and each side is trying to position itself as the most righteous,” Rosen told me. “Sometimes, the intraparty fights are the most vicious.”

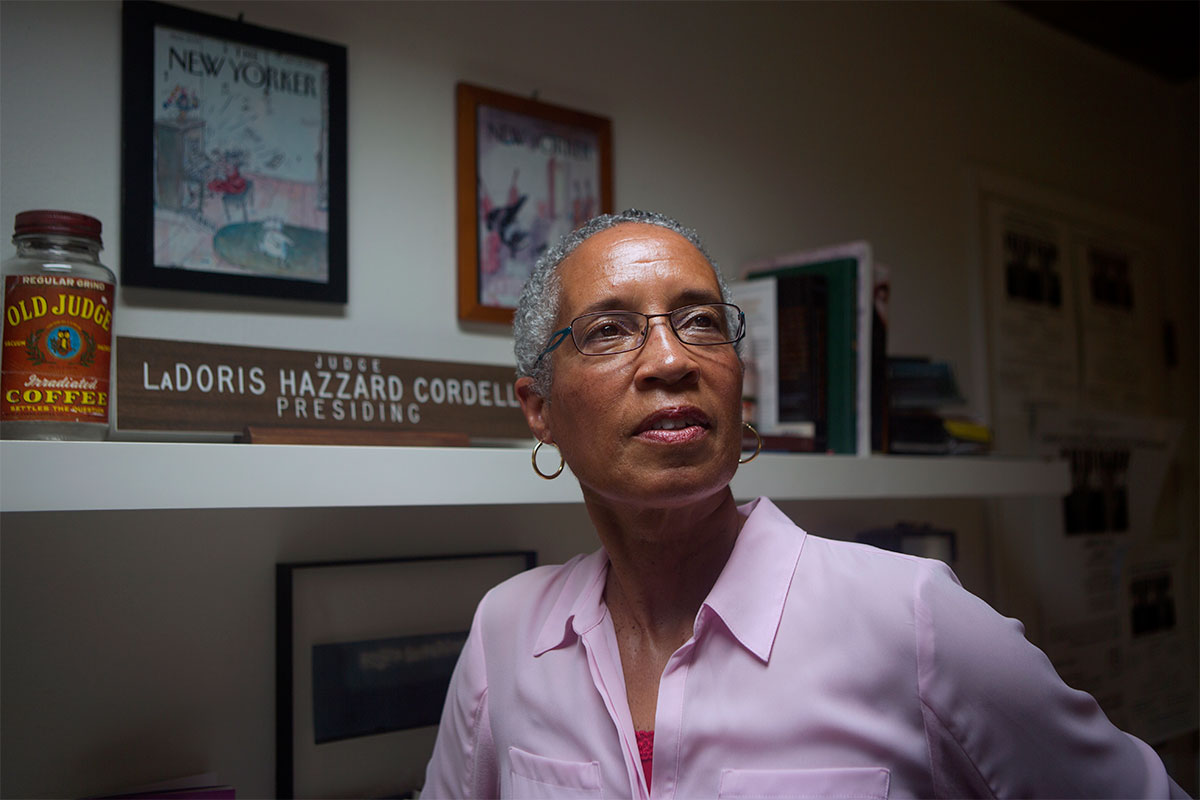

The de facto leader of the anti-recall campaign is LaDoris Cordell, a retired California Superior Court judge and staunch advocate of criminal justice reform. When I visited her in her sunny Palo Alto ranch-style house, she estimated that during her 19 years on the bench, she had sentenced thousands of people.

Initially, Cordell, who is black and gay, had been appalled by Turner’s short jail term. She told CBS News at the time that the mitigating factors Persky cited were “basically code for white privilege.” Later, when Dauber and Tsurkov dug up the case of Gunderson, the would-be University of Hawaii football player, Cordell told BuzzFeed, “There are so many problems with how this case was handled that I'm not even sure where to start.”

But as a former judge, the idea of recalling Persky was anathema to her. So, too, were Dauber’s tactics. Cordell cited the time when Dauber tweeted “Please enjoy this song,” linking to a ditty by a New Jersey duo called “F*ck Brock Turner” that encouraged him to “take a nosedive off the top of a cliff.” (Dauber later apologized.)

Cordell showed me a picture of a protester holding an assault rifle outside Turner’s parents’ home in Ohio. In the summer of 2016, a small crowd had gathered there, carrying signs with slogans like “If I rape Brock will I only do 3 months?” and “Shoot your local rapist.” “Brock Turner has become the poster boy for everything about rape culture,” Cordell said. “His life is ruined. When is enough enough?” Cordell hadn’t known Persky before the recall, but she was similarly affronted that Dauber had characterized him as a totem of white privilege. “His wife is a woman of color!” Cordell exclaimed, brandishing a blown-up Persky family portrait. “He has biracial kids!”

In Cordell’s telling, other recall opponents were too scared of Dauber to speak up until she stepped in. “She’s a bully, and bullying is not going to work with me,” Cordell said. She now seemed as consumed by the recall as Dauber was: “The recall is my life, 24/7.” Cordell spent much of our nearly three-hour interview discussing not the legal arguments, but Dauber herself, whom she described as “a smart, relentless, troubled human being.” She and her allies spoke of Dauber in terms that veered into deep suspicion, even paranoia.

For instance, Barbara Babcock, who in 1972 became the first woman appointed to teach at Stanford Law School, questioned whether Emily Doe really had a problem with Turner’s sentence. She pointed out that Emily Doe had told the female probation officer she didn’t want Turner to “rot in jail.” Emily had explained in court that these words had been “slimmed down to distortion and taken out of context,” but Babcock perceived a more malign influence: “Michele got ahold of her.”

A protest outside Brock Turner's parents' home in Ohio, after Turner's release. SPLASH NEWS

A protest outside Brock Turner's parents' home in Ohio, after Turner's release. SPLASH NEWS

Emily Doe’s statement, too, was the subject of fevered speculation among the anti-recall crowd. “I can’t prove it, but I think Dauber wrote the victim letter,” Cordell told me. Babcock echoed her suspicion. “It’s so sophisticated for someone who was so young,” she said. Persky’s lawyer, a fellow Stanford alum named Jim McManis, was also sure that Emily hadn’t written the statement. “A person whose identity I am not at liberty to disclose says that it was written by a professional battered women's advocate,” McManis explained. “I can't verify it, but the person who told me this, I value her judgment.”

I had seen some of Emily Doe’s other writing and believed the statement was her work—her voice, with its emotional charge, was immediately recognizable. The tone also sounded nothing like Dauber’s cerebral wood chipper. “I didn’t even suggest one change after I read it because it would be like changing something in the Mona Lisa. It’s a masterpiece,” Dauber fumed. “I think it’s deeply insulting not only to Emily Doe but to every other victim of sexual assault,” she went on, gathering speed. “This is a woman who had her agency taken away from her and that letter was her effort to regain some of that agency. And now they’re undermining her agency. It is unforgivable!” She paused. “You think that’s too much?”

In February, after Dauber reported receiving the envelope with white powder, Cordell told the local press that it had “the hallmarks of a publicity stunt.” Even though a man was arrested two weeks later—on charges of mailing threatening material to Dauber, Donald Trump Jr. and half a dozen others—Cordell insisted to me that the incident was “a hoax.”

During our conversation, Cordell also hinted that she had information from Dauber’s personal history that would reveal her motives. Later that evening, I got an email from Margaret Russell, another anti-recall lieutenant. Russell is a law professor at the Santa Clara University who sits on the national board of the American Civil Liberties Union. Her email contained years-old documents about Amanda Dauber, the child Dauber lost to suicide. I later found out that the anti-recall campaign had sent these to several reporters, but none had printed their contents.

When I asked Russell why she was sending the documents to me and how they were relevant, Russell wrote back a long, bristling letter—now she was suspicious of my motivation, too. She felt the documents explained Dauber’s behavior. “You may disagree, but I think her relationship with these young women helps fill the void created by the daughter she could not save,” she wrote. “I have tried to look at her with compassion and humanity. But she is so destructive that I feel ethically obligated to oppose her efforts to destroy (lots of) people and to destroy the judiciary.” That the recall’s opponents were doing exactly what they accused Dauber of doing to Persky—launching a personal, psychological attack—seemed entirely lost on them.

In April, Cordell invited Dauber to debate her at an event hosted by the Silicon Valley Republicans at a country club in the hills of Los Altos. Dauber canceled at the last minute and sent Marcus Cole, a fellow Stanford Law School professor and a black Republican, in her stead. “I bet this is the most black people they’ve had here!” Cordell whispered to me as the introductions got going. Once onstage, her argument leaned heavily on Brock Turner’s version of the night of the assault—in particular his assertion that Emily Doe had consented, which the jury had rejected. “They were making out, and at some point, he says to her, ‘Can I finger you?’” Cordell said. “According to his testimony, she said, ‘Yeah.’ Her underwear comes off, and he fingers her.” She made the attendant gesture as guests continued eating their poached salmon and rice.

When the debate was over, there was far less clarity than before the two sides had presented their arguments. I spoke to people who had supported the recall before the event but changed their minds by the time it ended, and vice versa. The vast majority, however, expressed profound confusion.

On May 8, less than a month before the ballot, The Mercury News endorsed the recall, and Persky finally broke his silence in a press conference hosted by Cordell. By this point, he was working from home as a night judge, on call from 5 pm to 8 in the morning. He had removed the numbers from the front of his house after his address was posted online. The judicial system was based on the promise, Persky said in his quiet voice, “that judges would rule on the facts and the law, not on public opinion.” He was still unable to discuss the specifics of the Turner case, but he highlighted a number of landmark judicial decisions in which judges had gone against popular opinion and granted rights to a minority, such as Brown v. Board of Education. Persky declined my request for an interview, but in an emotional conversation with The Associated Press, he said he had no regrets about how he had handled the Turner case, and accused the recall campaign of reducing a complex criminal case to a hashtag.

Aaron Persky said he had no regrets about how he handled the Turner case. JEFF CHIU/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Aaron Persky said he had no regrets about how he handled the Turner case. JEFF CHIU/ASSOCIATED PRESS

The two-year effort had taken its toll on Dauber, too. Her family was tired; she was tired. In a moment of exhaustion, she had totaled her car and was now cruising around liberal Palo Alto in a pick-up truck. But she had not lost an iota of her righteous self-assurance. “I know that what I’m doing is the right thing,” she said. I told her that multiple people had described her as a bully. “If I thought I had bullied someone, I would have apologized,” she said, clearly stung. “I have a history of being thoughtful, pragmatic and willing to compromise. I also have been unfortunately thrust into the role by Stanford of being a public critic, and that has not been a pleasant experience. It’s not fun be to be a whistleblower.” Still, she didn’t plan on relenting. “I’m going to keep trying to make Stanford a better place as long as I’m there,” she said.

The young woman who had inspired her crusade remained out of sight. I sent questions for Emily to the district attorney’s office; a spokesperson responded that “Emily Doe is not communicating with the media.” Meanwhile, Palo Alto is now peppered with the recall campaign’s flyers and lawn signs bearing Brock Turner’s mugshot from the night he assaulted her.

Brock Turner is living with his parents in Dayton. Records show that he was briefly enrolled at Sinclair Community College. His lawyer said that he was not doing interviews; a person familiar with his situation told me he was trying to keep a job and get an education. In December, Turner appealed his conviction. His legal adviser, John Tompkins, who refused to comment on the record, has told reporters that “what happened is not a crime.” Turner’s chief arguments are that there was not enough evidence to convict him on any of the three counts, that Persky should have permitted more of Turner’s character witnesses to testify, that Emily Doe consented before passing out, and that by referring so many times to the dumpster, Emily’s lawyer had prejudiced the jury “because of the inherent connotations of filth, garbage, detritus and criminal activity frequently generally associated with dumpsters.”

The dumpster is gone now. Last year, Dauber proposed turning the site of the assault into a small seated garden with a plaque quoting from Emily Doe’s statement, the words that had launched a movement. Stanford was open to the idea, but the project stalled over a disagreement between Dauber and Stanford over which quote to use. One of the quotes Stanford had suggested was “I’m right here, I’m okay, everything’s okay, I’m right here,” which Dauber felt missed the point entirely. Negotiations broke down, the fight spilled into the national media and no plaque was installed.

The spot where Emily Doe was assaulted was once a dirt trail behind a dumpster known to Stanford undergraduates as the “Scary Path.” Three years later, it is a clean, well-lighted place. Wooden benches sit atop local stones and a terra-cotta floor. During the day, the California pines offer shade and dappled sunlight. A fountain gurgles quietly. It is an incongruously peaceful testament to the clanging battle that started here. Without Emily Doe’s words, though, it is just two benches and a fountain, easy to overlook as just another place to sit. There is no ready lesson.

The site of Emily Doe's assault, now transformed. STANFORD DAILY

The site of Emily Doe's assault, now transformed. STANFORD DAILY