It was still dark outside when Amanda woke up to the sound of her alarm, got out of bed and decided to kill herself. She wasn’t going to do it then, not at 5:30 in the morning on a Friday. She told herself she would do it sometime after work.

Amanda showered. She put on khakis and a sweater. She fed Abby, her little house cat. Before walking out the door, she sent her therapist an email. “Not a good night last night, had a disturbing dream,” she wrote. “Got to try and get through the day, hope I can shift my mind enough to focus. Only plan tonight is to come home and take a nap.”

Amanda was a 29-year-old nurse, pale and thin—a quiet rule-follower. She had thought about taking a sick day, but she didn’t want to upset her co-workers or draw attention to herself. As usual, she arrived at the office earlier than just about everyone else, needing the extra time to get comfortable. She had taken a pay cut to join this clinic outside Seattle, in part because she wanted to treat low-income mothers and pregnant women. Some of her patients were in recovery, others were homeless, several had fled physically abusive men. She was inspired by their resilience and felt only slightly jealous of the ones who had found antidepressants that worked. That day, September 28, 2007, was her first shift seeing patients without a supervisor watching over her.

Amanda’s schedule was relatively light: three, maybe four patients. She measured their blood pressure, their weight. She ran through her mandated checklist of questions. Have you relapsed since your last visit? Can you afford your newborn’s car seat? Do you have a history of mental health problems? She hated those questions. There was no way she would answer them herself. Too invasive, too personal. In an email she’d sent her therapist a month earlier, she confessed that she would occasionally put on a “mask of normalcy.” Sure, patients were always commenting on how upbeat she was, but “the part they didn’t see,” she wrote, “was me turning around, me leaving the room, me getting in my car at the end of the day, taking a deep breath and me crying all the way home. I have always done what is needed to be done and when I can stop pretending I let it out.”

Her first thoughts of suicide had come shortly after her 14th birthday. Her parents were going through an ugly divorce just as her social anxiety and her perfectionism at school kicked in hard. At 20, she tried to kill herself for the first time. For about the next decade, Amanda didn’t make a few attempts. She made dozens. Most times, she would take a bunch of pills just before bedtime. That way, her roommates would think she was sleeping. In the mornings, though, she would wake up drained and spaced out, despairing that she could fail even at this. Then she would resolve not to speak of it to anyone. To her, suicide attempts weren’t cries for help but secrets to be zealously guarded.

“What in the world is it going to take for me to feel better?” Amanda asked in an exasperated diary entry from 2004. Therapy wasn’t much help—too often, her pain was met with baffling ignorance or worse. A counselor at her church suggested that her depression would go away if she prayed more. Once, a therapist refused to talk during their session unless she opened up; she never went back after that. The college where she studied nursing forced her to take a leave of absence over her depression and anxiety. The day she got the news, she made another suicide attempt.

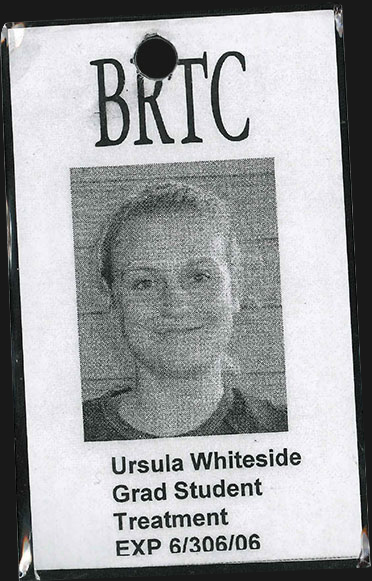

Ursula Whiteside, Amanda’s new therapist, was different. She was just 29 years old, a graduate student working under supervision at a University of Washington lab. Amanda was one of her first clients. But Whiteside was preternaturally sensitive. She could tell how just sitting in the waiting room stoked Amanda’s social anxiety. And she made it clear that she would go to creative lengths to get Amanda talking. During one session, Whiteside stood on her head. In another, she took Amanda into a children’s playroom, thinking the absurd change of scenery would shake something loose. The rare moments when Amanda responded with a dry joke were gold.

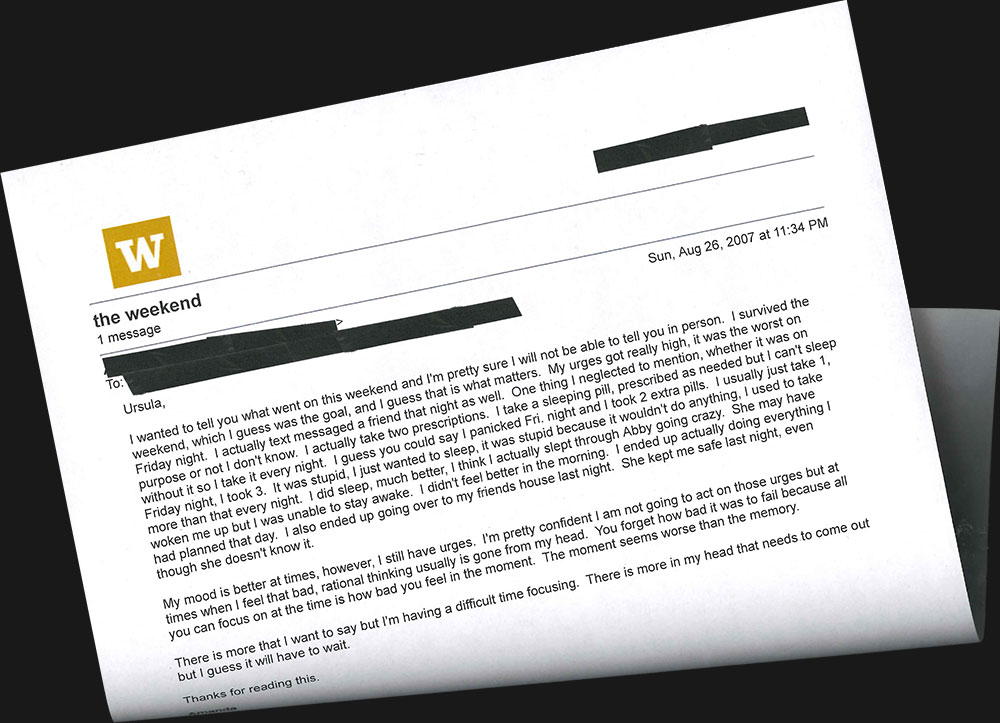

Still, there were sessions that ended in frustration, so they agreed to email between appointments. Amanda wrote to Ursula whenever the mood hit her, late at night mostly. The emails could be short, no more than a few paragraphs, but here, more than anywhere else, she was matter-of-fact about her suicidal thinking. “I wanted to tell you what went on this weekend and I’m pretty sure I will not be able to tell you in person,” she wrote on August 26. “I survived the weekend, which I guess was the goal. … I panicked Fri. night and I took 2 extra pills. I usually just take 1, Friday night, I took 3. It was stupid, I just wanted to sleep, it was stupid because it wouldn’t do anything. … I also ended up going over to my friends house last night. She kept me safe last night, even though she doesn’t know it.”

Whiteside’s replies often teemed with exclamation points and underlined words. She knew it was important to remain upbeat. But a month later, when she received the email Amanda sent that Friday morning before work, she wrote back quickly and with little of her typical flair. They’d had a session the day before, and Amanda seemed to be hiding more than usual. Whiteside felt it was necessary to jolt her into being more forthcoming.

“If you are planning on killing yourself this evening or this weekend, I need to know,” Whiteside wrote just before 7 a.m.

Then she waited. 10 a.m. Noon. No reply. By 1:30 p.m., Whiteside called her supervisor to discuss strategy. If Whiteside’s instincts were correct, and she asked the police to do a welfare check, she could save Amanda’s life. If she was wrong, she could destroy the trust they had built over their months together, and Amanda might not return for another session. Whiteside started typing up notes. “I’m glad that she is telling me something,” she wrote. “But something is getting in the way of her being completely forthright. … As good as I am, I can not magically help someone feel better. … So terrifying that she is going to go all the way to the bottom.”

Amanda left work at 4:30 p.m. and stopped at a local pharmacy to refill a prescription. She wanted to make sure she had enough antidepressants to successfully overdose. She then went home and gathered up other sleeping meds so that she could mix them together with the new pills. She never replied to Whiteside. She didn’t write a suicide note. After dark, she put on her pajamas and brushed her teeth. She took a deep breath, methodically swallowed one pill after another, dozens and dozens of them, laid down on her bed and drifted off to sleep.

Meanwhile, Whiteside had a lot of work to do, but her mind kept returning to Amanda. She was so worried that she forgot that she had driven to the university that morning and took a bus home. She kept leaving voicemails and texts, telling Amanda that she cared about her, that she was confident the therapy could work. That night, she finally called the police. She knew the risks; she just didn’t care anymore.

But when the cops arrived, Amanda was nowhere to be found: The address Whiteside had was out of date. Helpfully, an old neighbor gave the police the number of one of Amanda’s friends. The friend, though, insisted on meeting the police in person, eating up valuable time. By the time she took them to Amanda’s studio apartment, it was late, maybe five or six hours after Amanda had ingested the pills. They found Amanda in bed, alive but clearly out of it. There were empty pill bottles nearby, cat toys underfoot. Her friend shook her awake. In a sleepy whisper, Amanda confirmed what she had done.

Several hours later, Amanda came to in the emergency room. She had an IV drip in her arm. An oxygen mask covered her face. Medical personnel monitored her extremely low blood pressure and x-rayed her chest. She could hardly speak, but the staff got enough information to describe her in their medical records as “a 29-year-old previously healthy, except for her psychiatric history.”

In time, Amanda was transferred to another part of the hospital, where a “sitter” was assigned to observe her in case she tried to harm herself. During a psychological assessment, she frequently dozed off. She couldn't believe she was here again. She didn’t call any friends or family members. Her state of mind was exactly the same as it was when she started downing the pills. Amanda still wanted to die.

Over the last two decades, suicide has slowly and then very suddenly announced itself as a full-blown national emergency. Its victims accompany factory closings and the cutting of government assistance. They haunt post-9/11 military bases and hollow the promise of Silicon Valley high schools. Just about everywhere, psychiatric units and crisis hotlines are maxed out. According to the most recent figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there are now more than twice as many suicides in the U.S. (45,000) as homicides; they are the 10th leading cause of death. You have to go all the way back to the dawn of the Great Depression to find a similar increase in the suicide rate. Meanwhile, in many other industrialized Western countries, suicides have been flat or steadily decreasing.

What makes these numbers so scary is that they can’t be explained away by any sort of demographic logic. Black women, white men, teenagers, 60-somethings, Hispanics, Native Americans, the rich, the poor—they are all struggling. Suicide rates have spiked in every state but one (Nevada) since 1999. Kate Spade’s and Anthony Bourdain’s deaths were shocking to everybody but the epidemiologists who track the data.

And these are just the reported cases. None of the numbers above account for the thousands of drug overdose deaths that are just suicides by another name. If you widen the lens a bit to include those contemplating suicide, the problem starts to take on the contours of an epidemic. In 2014, the federal government estimated that 9.4 million American adults had seriously considered the idea.

There’s an inherent lack of closure to suicide. Even when people write notes, they can reveal so little. Suicides often leave loved ones, acquaintances and co-workers to question themselves for the rest of their lives. And in their own grief, they, too, can entertain dangerous thoughts. “With suicide you have that added trauma to it,” said Julie Cerel, the president of the American Association of Suicidology. “The ‘why’ question of trying to search for meaning when there’s no meaning available—If I only had a note. If I only talked to the last person that they talked to. The ‘onlys’ can be torturous.’” Last year, Cerel published a study examining the consequences of suicide and found that each one could affect as many as 135 other people.

The fundamental mystery of suicide has long made it an object of fear and contempt within the medical establishment. Since the 1950s, public health officials have tried hotlines, individual therapy, group therapy, shock therapy and forced hospitalizations. Doctors have taken away people’s shoelaces and belts and checked in on attempt survivors every 15 minutes to make sure they are still safe. They have coerced patients into signing contracts swearing that they would not kill themselves. They have piled on psychiatric medications with ever-more invasive side effects, only to watch the number of suicides continue to climb.

Even now, most mental health professionals have no idea what to do when a suicidal person walks through their door. They’re untrained, they’re under-resourced and, not surprisingly, their responses can be remarkably callous. In an emergency room, an attempt survivor might be cuffed to a bed and made to wait hours to be officially admitted, sometimes days. Finding help beyond the ER can be harder yet.

“You take someone who is not doing well, shutting down, and throw them in a system that requires them to have the highest problem-solving abilities and emotional regulation,” said Jeff Sung, a psychiatrist colleague of Whiteside’s who works with high-risk clients and trains others to do so. According to federal data, the majority of those in need of mental health services do not receive it.

When confronted with the coldness of her colleagues, Whiteside grows exasperated. Because while the dead are invisible to most, she knows them. She gets how suicidal thoughts have their own seductive logic, how there is comfort in the notion that there is a surefire way to end one’s pain. She sees why people might turn to these thoughts when they hit a crisis, even a minor one like missing a bus to work or accidently bending the corner of a favorite book. That’s why suicidal urges are so much more dangerous than depression—people can view death as an answer to a problem. And she knows that many patients of hers will always feel vulnerable to these thoughts. She has described her job as an endless war.

Whiteside was born in Colville, Washington, 40 years ago, the first child of parents drawn to adventurous work wherever they could find it: building an oil pipeline in Alaska, raising cattle and conducting child health screenings in rural Washington, driving trucks through the Midwest. By the time she attended junior high, in Minnesota, Whiteside had enrolled in six different schools in three different states. But instead of turning her bitter or shy, all the moving seemed to sharpen her empathic powers. She became one of those canny little people who could intuit when those around her were in pain.

And she could be impulsive in her efforts to help. When she was in eighth grade, one of her best friends called her frantic and in tears. The friend didn’t go into detail, but said that she needed to escape her house immediately. So Whiteside planned a rescue. Shortly after midnight, Whiteside snuck out of a window in her family’s basement apartment and stole her mother’s sedan. She didn’t think about the fact that she couldn’t drive legally or that her friend’s house was 8 miles away or that the roads were icy and covered in snow. She didn’t care that she weighed only 80 pounds and could barely see over the steering wheel. She made it past the McDonald’s, down the hill, to the one-lane country road where her friend lived before crashing the car into a ditch in front of the house.

The older Whiteside got, the clearer it became that she was better at looking after others than herself. In high school, she struggled with her body image along with depression and anxiety. Like her future clients, she found it excruciatingly difficult to talk about what she was experiencing. The idea of asking for help was “the scariest thing I could imagine,” she said. During one point in college, she sent her mother, who had lost her own brother to suicide, a lengthy letter detailing her ups and downs. “I’m writing you this letter because I often have a hard time saying out loud what I mean,” she confessed. “I am just chicken.”

She wanted so badly to understand the mechanics of despair, including her own. “Everything I do has to be extreme,” she wrote in her diary. “I go through phases where I absolutely love myself—I go through others where all I can think about is knives and bridges.” At the University of Minnesota-Duluth, she read mental health textbooks and academic journals in her spare time. She was drawn to the field as a practical way of untangling life’s most intractable problems. “I took my first psychology class and I was like, ‘Oh my God, you can actually change things,’” she said. “It’s not magic.”

Before her junior year, Whiteside transferred to the University of Washington so she could learn from Marsha Linehan, a legend in the field of suicide research. Linehan had pioneered a powerful form of treatment called dialectical behavior therapy, or DBT, which trains patients how to reroute their suicidal impulses. It can be grueling, emotionally exhausting work that requires people to spend several hours a week in individual and group therapy, and therapists to do check-in calls as needed throughout the week. Linehan had a principle for all of her students: Clients came first, your own life came second.

It couldn’t have suited Whiteside better. “I’ve found some semblance of passion,” she wrote in her diary at the time. “I have to think of myself and I have to think of my soul and I have to remember those in most need, those experiencing suffering beyond my imagination.” In a letter of recommendation, Linehan wrote that Whiteside had “become unflappable.”

And then Whiteside sprinted nose-first into the wall of the modern-day behavioral health care system. She took a clinical internship in the psychiatric department of Harborview Medical Center in downtown Seattle, an under-resourced, grim institution. The main goal, she kept hearing, was triage. She was there to stabilize suicidal patients, nothing more, because no one had the time to do more.

Whiteside was tasked with probing patients for their treatment history and state of mind. There was the man who killed his dog and shot himself in the stomach. The immigrant who set himself on fire. The college student who had been found walking in the middle of a street clutching a teddy bear. Each one, she felt, was desperate for any form of help or kindness.

“I was absolutely insane, completely unconcerned with life,” one former patient from that era said. “They had no idea what to do with me. But Ursula was looking at me in a way where she was actually waiting for me to respond. … It wasn’t, ‘What are your symptoms? What medications are you on?’ It was, ‘Tell me a little bit about your story.’” Whiteside knew that people who leave the hospital after a suicide attempt are at a greater risk of harming themselves again within 90 days. And yet the doctors at Harborview were only providing referrals for clinics most patients would never visit or putting patients on waiting lists for therapists who might not be right for them. “These patients were basically at this critical juncture,” Whiteside said, “and we were fucking blowing it.”

After her patients left the hospital, she couldn’t stop thinking about them. So she began tracking them down, calling to see if they needed help or just to let them know they were on her mind. She handed out her phone number to patients before they left the hospital. On the back, she’d also leave a personal note. Anything to keep them tethered to the world. For six months, she called a woman who had made an attempt after a breakup. The woman took Whiteside’s calls for a while, until she didn’t. Whiteside still doesn’t know what happened to her.

“It was almost an existential crisis for her,” says Sarah Stuckey, one of Whiteside’s best friends from the clinical world. “She’s the velvet hammer in so many ways. She’s this beautiful woman talking in this soft voice about these horrible things. You lose people. That takes a toll. You have very close calls with people. That takes a toll.”

Whiteside was becoming so anxious about her work that she had days when she could hardly sleep or eat. One night after her internship was over, she uncorked a bottle of wine. She drank until she didn’t care if she ever woke up. This scared her. For just a few moments, she realized how it felt to be suicidal.

Months later, Whiteside met with her therapist to discuss how she could handle these feelings of powerlessness. Whiteside brought up the work of a long-retired psychiatrist and suicide researcher named Jerome Motto. He wasn’t well-known. But Whiteside’s mentor Marsha Linehan was enamored of him because he was the only American to devise an experiment that dramatically reduced suicide deaths. His technique didn’t involve a complicated thousand-page manual to follow or $1 billion in pharmaceutical research and development. All he did was send occasional letters to those at risk.

Right there in therapy, Whiteside found herself spouting out everything she knew about Motto’s approach and career. She began to cry. “Oh my God,” she said. “What if this is what we should be doing? What if it’s that simple?”

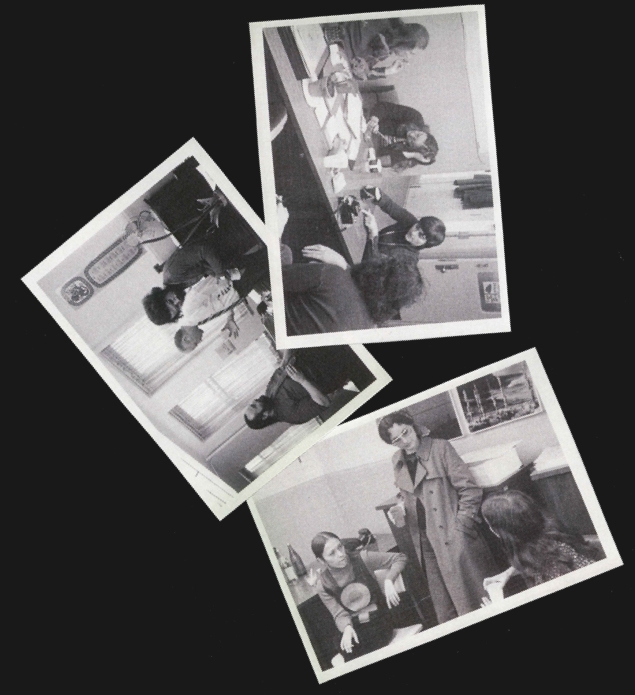

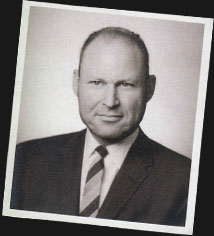

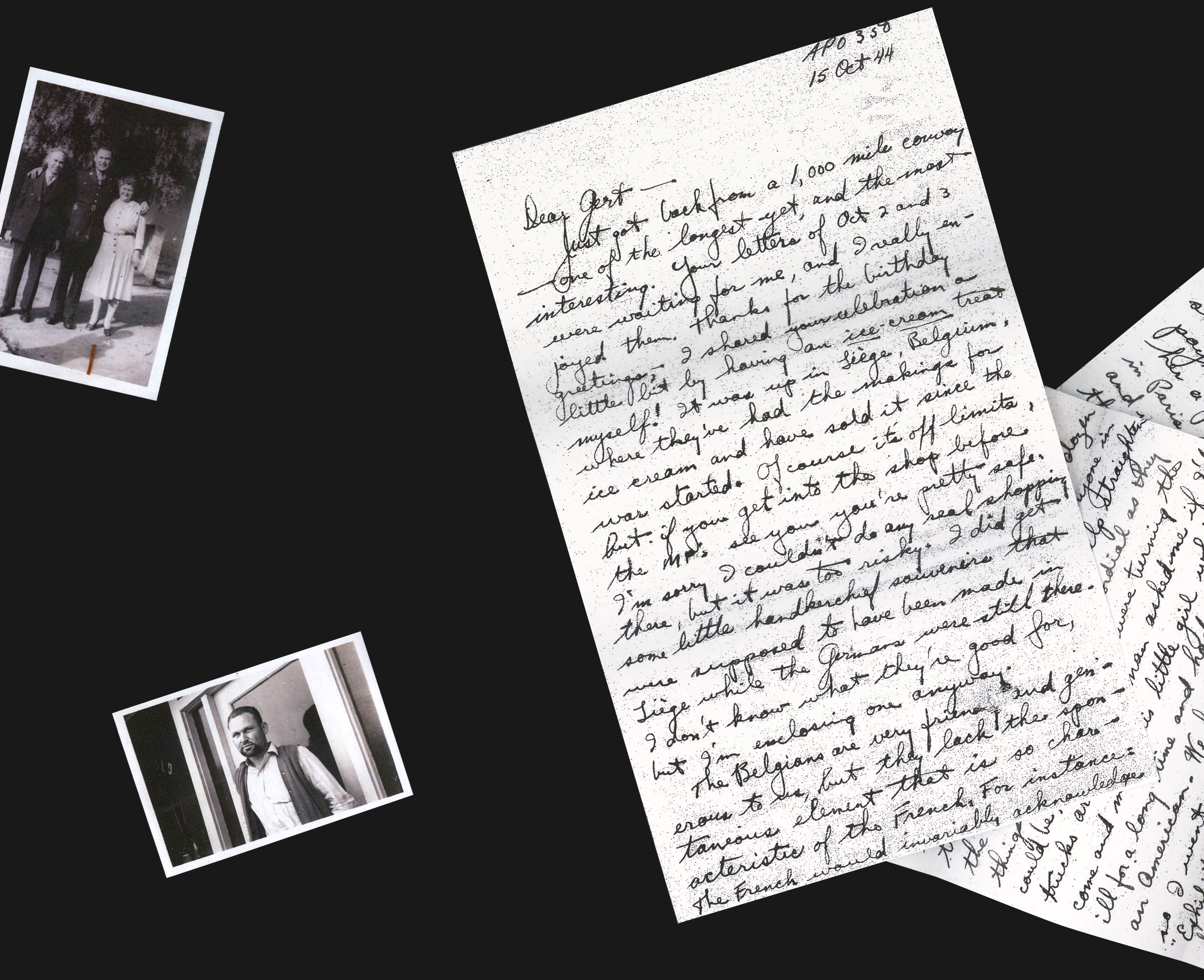

It was December 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge, and the 3989th Quartermaster Truck Company had been stuck for days in a farmhouse in Bastogne, Belgium, surrounded on all sides by German forces. In the quiet moments, when the sky was the color of bleach, and snow blanketed the ground, First Lieutenant Jerome Motto prayed for Allied planes to save him and his fellow soldiers. And just often enough, C-47s would appear with the precious cargo that kept them alive. The men would dash outside, trying to avoid detection or dodge enemy fire as food, clothes and medicine fell in gigantic bundles tethered to red and blue and green and yellow parachutes. To Motto, it looked like a sky wearing polka dots.

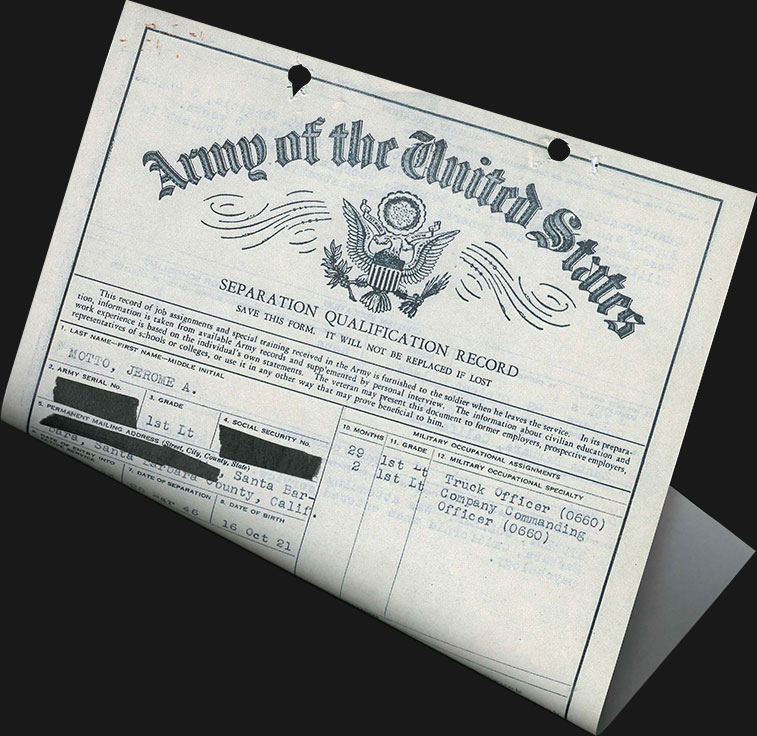

The tall, blue-eyed son of Jewish immigrants, quiet and self-effacing, Motto had grown up in Santa Barbara, California, harboring dreams of becoming a concert pianist. But when the war broke out, he had been eager to contribute what he could. During his Army intake, he requested to be assigned to clerical duty or perhaps a military band with the other introverts and artists. Instead, he was placed in a truck regiment, responsible for the safety of 39 other men.

The 23-year-old mostly kept to himself, driving through occupied Europe with a French grammar book on his lap. For the first time, he saw the world as a landscape of the traumatized. His convoy passed villages pocked with shattered storefronts and roofless homes, the streets empty of any young men like him.

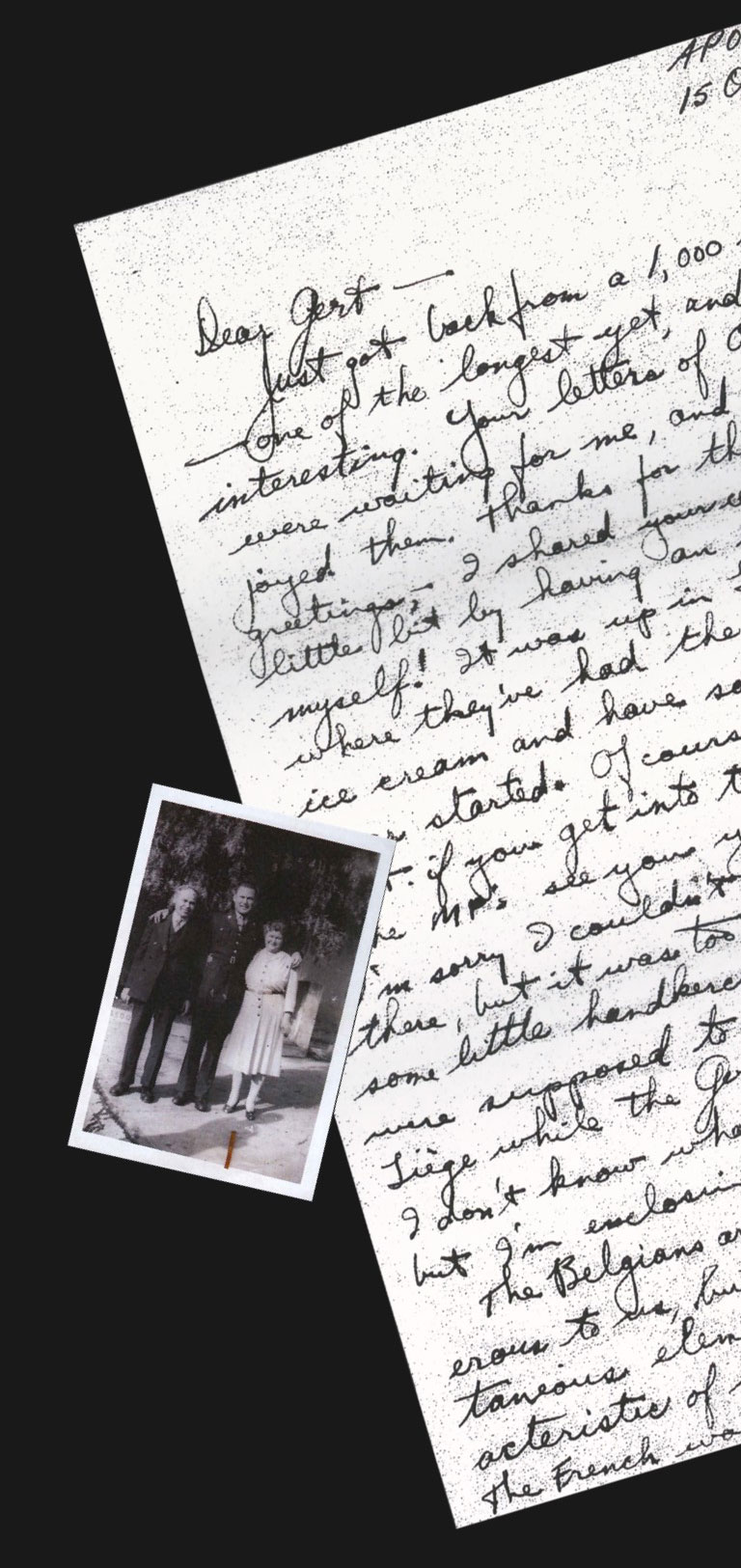

Amid the devastation, Motto was always on the hunt for small things to ease his mind. Photography helped. So did writing letters to his family. He told them about his burgeoning interest in psychology, brought on by seeing even the most macho of his fellow soldiers struggle to keep it together. His family’s replies, though, didn’t always bring comfort. They chided him for not writing enough, and when Motto read about an older sister’s divorce or his father’s mysterious illness, he only felt guilty, since there was nothing he could do from so far away.

To his surprise, his greatest solace came in the form of letters from a woman he barely knew. Motto had gone out with Marilyn Ryan about a half-dozen times while he was doing training in northwest Arkansas in the summer of 1943. It wasn’t serious: a few shows, a double date. But after he shipped out, she wrote to him. At first, he didn’t quite recognize her name. He answered simply to maintain the correspondence.

Her letters kept coming, whether he replied or not. Over time, he grew so attached to them that he felt the need to analyze why. They weren’t love letters exactly. “She just wrote of commonplace things—what she did during the day, and how cold it was getting, and what tunes were on the hit parade, + hello to Jim, and all that stuff,” Motto confided in a letter to an older sister. “Once in a while a wistful remark about how nice it would be if we could see each other again. No passionate drivel, though—just the implication that anyone writing so consistently must be sincerely interested.”

Almost inevitably, months into their correspondence, Motto found himself falling for Ryan. He tried to broach the subject of a deeper relationship: “Why in hell don’t we get it off our chests instead of remaining so painfully noncommittal?” But her response is lost to history. All that is known is that they continued writing each other, that Motto told his family several times about a girl in Arkansas (“a mighty potent morale builder”) who was “marking time” until he got back—and that although they flirted with the idea of a reunion, Jerome Motto would die in 2015, more than 60 years later, never having seen her again.

Still, her influence would shape the rest of Motto’s life. After the war, he studied psychology at Berkeley, completed medical school at UC San Francisco and then took a residency at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore before returning to the Bay Area. He was drawn to suicidal patients, men and women who resembled the shell-shocked soldiers he once transported. “Somebody has to speak for those who are not so strong, who are fearful, who are discouraged, who are distrustful of helpers, who are despairing, who are timid,” he recalled thinking at the time.

That was a fairly radical philosophy in the postwar years. In almost every social and medical circle back then, the act of killing oneself was considered to be more of a sin than a tragedy. Obituaries whitewashed suicide deaths as accidents. Catholics wouldn’t allow suicide victims to be buried in consecrated ground. In some states, attempting suicide was a criminal act. Medical schools tended to ignore the subject entirely, and many doctors considered it a “success in their practice” if they avoided suicidal patients, said Seymour Perlin, a colleague of Motto’s. Some years later, another colleague was in the emergency room when a young woman was rushed in. She had slashed her wrist and was barely conscious. The surgeon arrived, made sure she was alert enough to understand him and then said, “Next time, why don’t you just jump off the Golden Gate Bridge?”

All around him, Motto saw suicidal patients being made to feel alone. In 1965, he chanced upon a collection of papers by a German psychoanalyst named Hellmuth Kaiser. Kaiser argued that the most disturbed patients could be helped if they felt a sense of connection, even on a subconscious level. This got Motto thinking about Marilyn Ryan and how her letters had gotten him through the war, her sincerity dispensed as steadily as an intravenous drip.

“My own experience—it didn’t prove anything, of course,” Motto told me years later. But he wondered if the simple act of showing people that he was there for them—and expected nothing in return—would make suicidal patients feel less isolated, less in conflict with themselves.

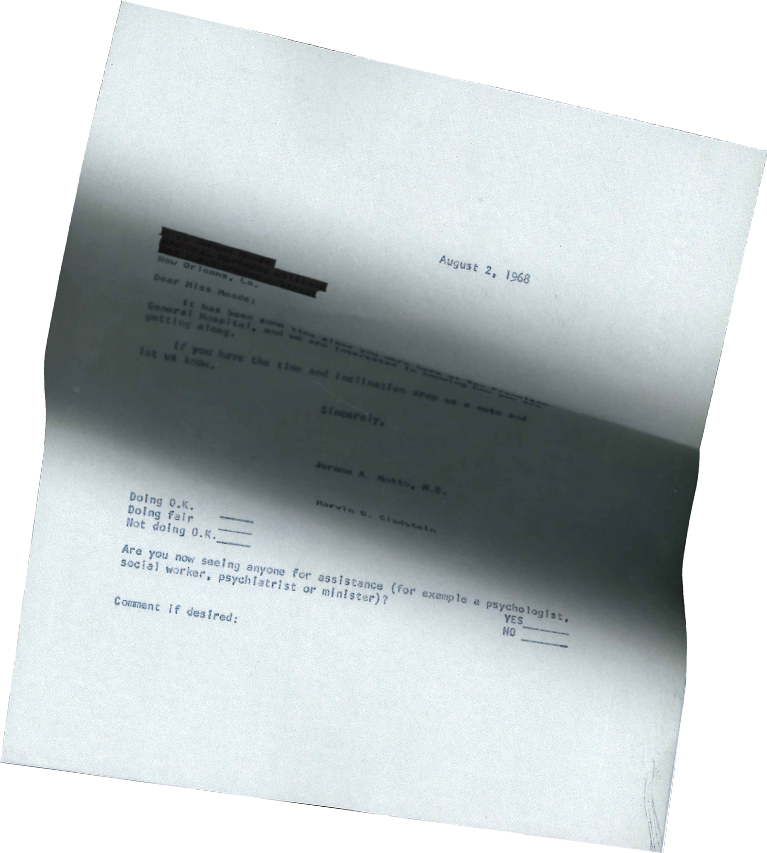

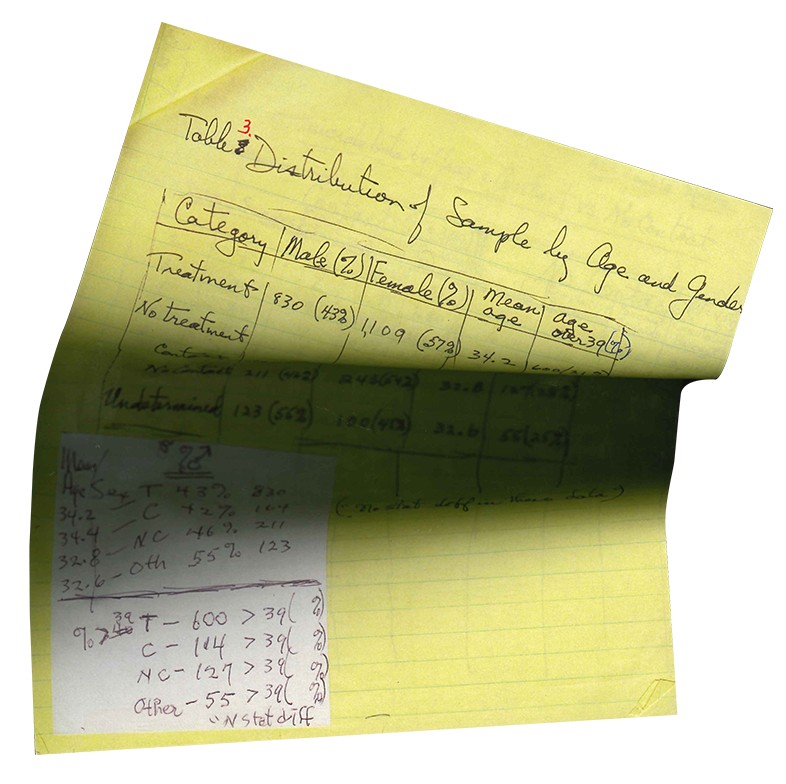

So, in the late ’60s, with a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, Motto devised a research project. He would track patients who had been discharged from one of San Francisco’s nine psychiatric facilities following a suicide attempt or an extreme bout of suicidal thinking—and he would focus on the ones who refused further psychiatric treatment and therefore had no relationship with a doctor. These patients would be randomly divided into two groups. Both would be subject to a rigorous interview about their lives, but the control group would get no further communication after that. The other one—the “contact group”—would receive a series of form letters.

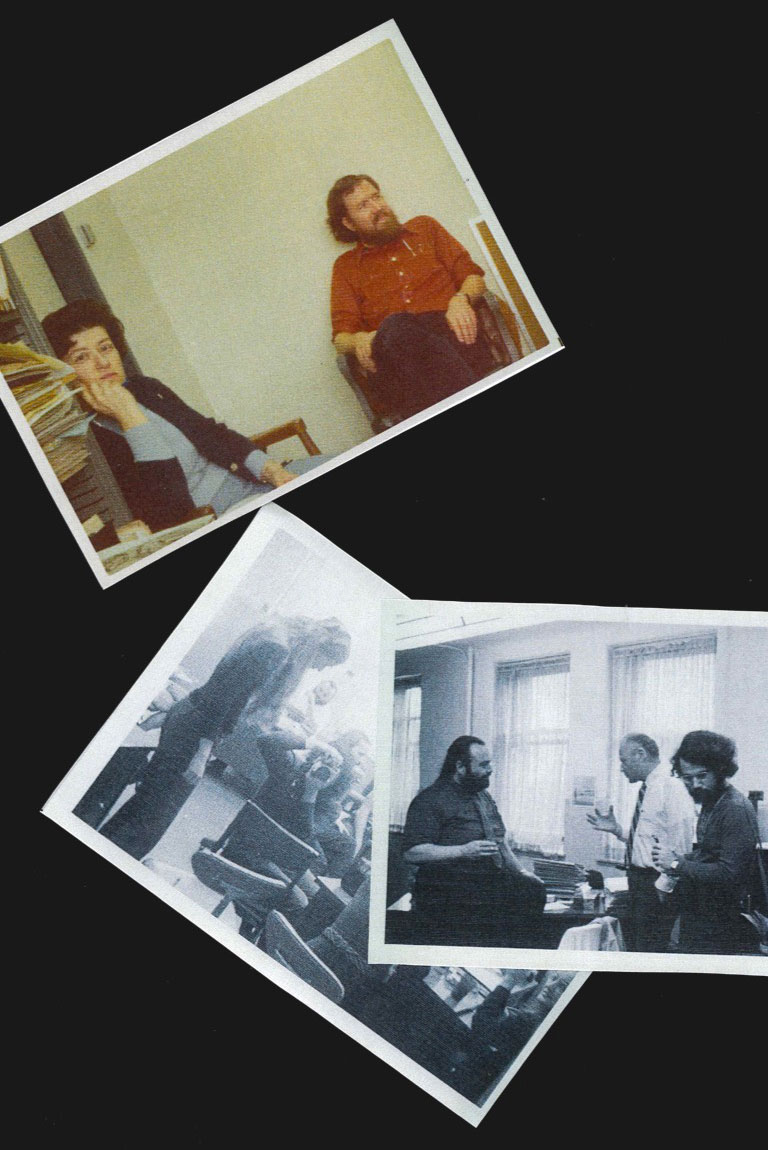

It was a wildly ambitious undertaking. To produce meaningful data, the study would take years and require the participation of thousands of patients, the maintenance of hundreds of thousands of pages of notes and the constant writing of letters in the spirit of Marilyn Ryan’s. Motto secured office space right above the emergency room at San Francisco General and assembled an unorthodox squad of researchers to interview and correspond with all the patients. At various times, his team included a woman studying to be a rabbi, a man who had recently left seminary to get his Ph.D. in psychology, a gay minister shunned by his congregation and a former nun.

“One thing I realized in working with suicidal people was that the problem spanned so many disciplines,” Motto told the writer Peter Shore in 2006. “It wasn’t just a psychiatric problem. It was a psychological problem, a public health problem, a social problem, a philosophical problem, a theological problem. When I say theological, I mean when the patient says to you, ‘What’s the point in going on? It’s just painful. I’m going to die sooner or later anyway. What am I here for? What’s the meaning of my life?’ Well, I realized they hadn’t given an answer to that question to me in medical school.”

For the willing study participants, Motto created a 39-page questionnaire to document the finest details of their lives. He had researchers ask patients how old their next-younger sibling was, what their spouse did for a living, how many moves they had made in the previous five years and whether they were currently living in an apartment or a hotel. (And how big was the hotel?) Unlike other medical professionals, he also had his team pose pointed questions about patients’ suicide attempts: What had led to their decision? Had they sought help beforehand? What effect did the attempt have on their consciousness? How would they make their next attempt?

Motto insisted that his researchers memorize the questions so the exchanges wouldn’t feel clinical and instructed them to show unconditional acceptance. The interview might start with something like, “Tell me more about how you got here.” Certain patients badly wanted to talk. Others couldn’t. Some bore fresh wounds along their throats from attempted hangings. In the first year and a half, 16 patients died by suicide before they were randomized into the trial. Even the more experienced researchers were taken aback by the severity of the pain people were living with. Chrisula Asimos, who would become the study’s longest-serving researcher, once sought Motto’s advice about a participant who was particularly closed-off. “Motto just said, ‘You sit with the person and you be with that person for as long as it takes. At some point, they will get it,’” Asimos recalled.

The former nun, Patricia Conway, spent many hours over several days with a mother who was barely able to utter a word after her suicide attempt. One afternoon, the woman seemed transfixed by another patient who was screaming and thrashing nearby. After a long silence, she said, “Isn’t he lucky?”

Conway asked why.

“You may think he’s crazy, but he’s able to tell you what he’s feeling,” the woman replied. “He’s able to scream and yell and talk about it. But I can’t.”

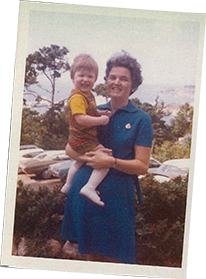

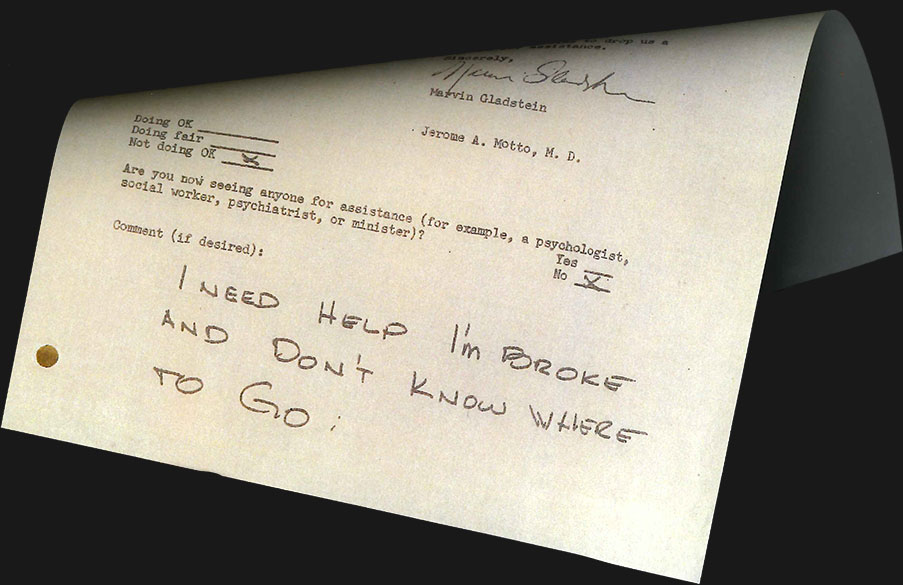

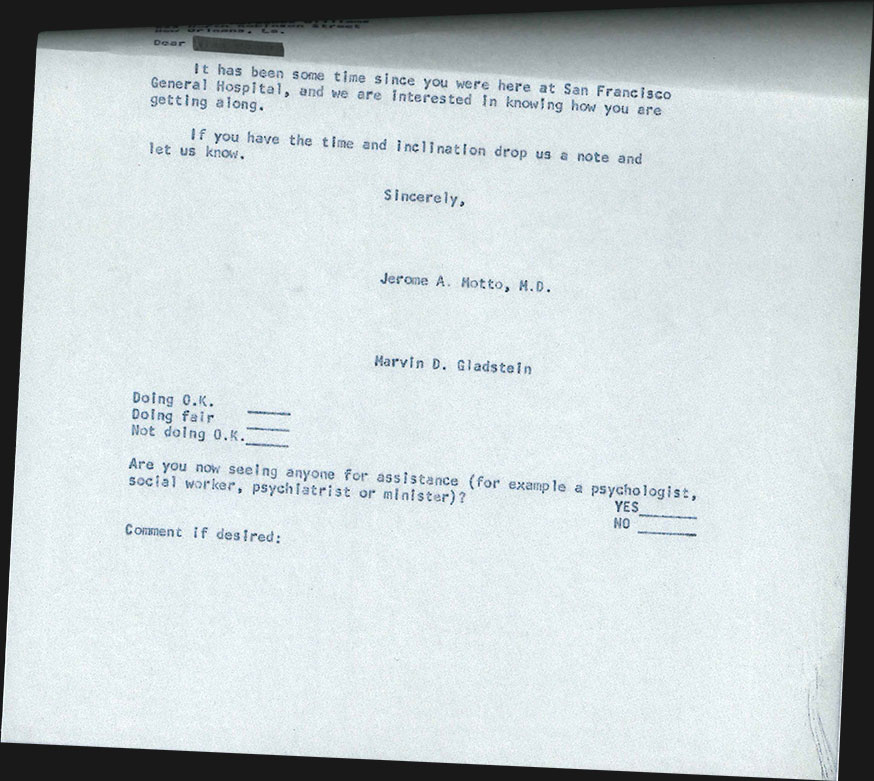

It seemed so ridiculous: letters that could pull a person out of an abyss that deep. Not personal messages, but form letters typed out on one of the office’s IBM Selectrics. Motto wanted them to be simple and direct, with no clinical jargon or ass-covering fine print. Most importantly, they had to demand nothing. “No expressions like ‘you really should try to resume therapy’ or ‘would you fill out this depressive scale so we can determine what your status is?’” he said. It ought to convey a genuine sense of kinship—“simply what one might say to a friend.”

Motto didn’t take long to write the first letter a patient would receive. He knew what he wanted to say, hitting upon two sentences—37 words—that felt just right: “It has been some time since you were here at the hospital, and we hope things are going well for you. If you wish to drop us a note we would be glad to hear from you.”

With each letter they sent out, the research team’s secretaries enclosed a self-addressed envelope. Motto insisted that it not include a stamp. “That’s important,” he later explained, “because some of these persons were so sensitive that putting the stamp on the envelope would be pressure, that they’d feel obligated that we wouldn’t waste our stamp.”

The letters were to be mailed on a set schedule: once a month for the first four months; every two months for the next eight months; every three months for the next four years. In all, the correspondence would include 24 letters, sent over the course of five years, that would vary subtly. Some of the subsequent templates included:

“This is just a note to assure you of our continuing interest in how you are getting along.”

“Just a note to say that we hope things are going well, as we remain interested in your well being. Drop us a line anytime you like.”

“We realize that receiving a letter periodically expressing our interest in how things are going may seem a bit routine. However, we continue to be interested in you and how you are doing. We hope that our brief notes will be one way of expressing this.”

Motto’s study had the potential to be reputation-killing. Charlotte Ross, who founded a suicide prevention and crisis center in the Bay Area and frequently collaborated with Motto on research papers, put it bluntly: At that time, the idea of following up with suicide attempt survivors after they called a hotline was “as reputable as ambulance-chasing.” When Asimos told her colleagues at the psychiatric hospital about the project, they found it hysterical. “Are you kidding?” one gasped. “Why would you think just sending out a little letter was going to make a difference?”

There were other, more practical obstacles. The researchers had little way of knowing if their letters would make it to their targets—maybe they’d go to an old address or get lost between department store catalogs in the mail. All Motto and his researchers could do was enroll patients, send the form letters and wait. Between 1969 and 1974, Motto’s researchers interviewed more than 3,000 patients.

Even as staff members came and went, leaving for new jobs or graduate school, the nature of their work with Motto—the long hours, the lives at stake—brought everyone close. They organized potlucks and tennis matches, which Motto always won. Conway remembers going to jazz shows with another researcher who warned her: “This is not going to be very nunny.” The secretaries attended a feminist rally and then persuaded Motto to let them wear pants to work. And the researchers kept finding new ways to connect with suicidal people. They designed a support group for attempt survivors and took them out dancing. When the stress of the project got to be too much, they turned to each other for encouragement. This being the early ’70s, there were a lot of office shoulder rubs.

Conway often found herself talking to Motto over coffee in the morning or at his desk during lunch. They would chat about what they were reading—Motto was fond of the countercultural poet Kahlil Gibran—and she was immediately attracted to how passionate he was. She liked that he fumed about the Vietnam War, shooting off so many letters to his congressman that a staffer wrote back telling him to stop. (Motto kept writing him anyway.) Their talks soon developed into something more, and within a year of their first date, the 48-year-old Jew-turned-Unitarian and the 33-year-old former nun were married. Conway’s mother gushed that Motto was “the most Jesus-like person” she had ever met.

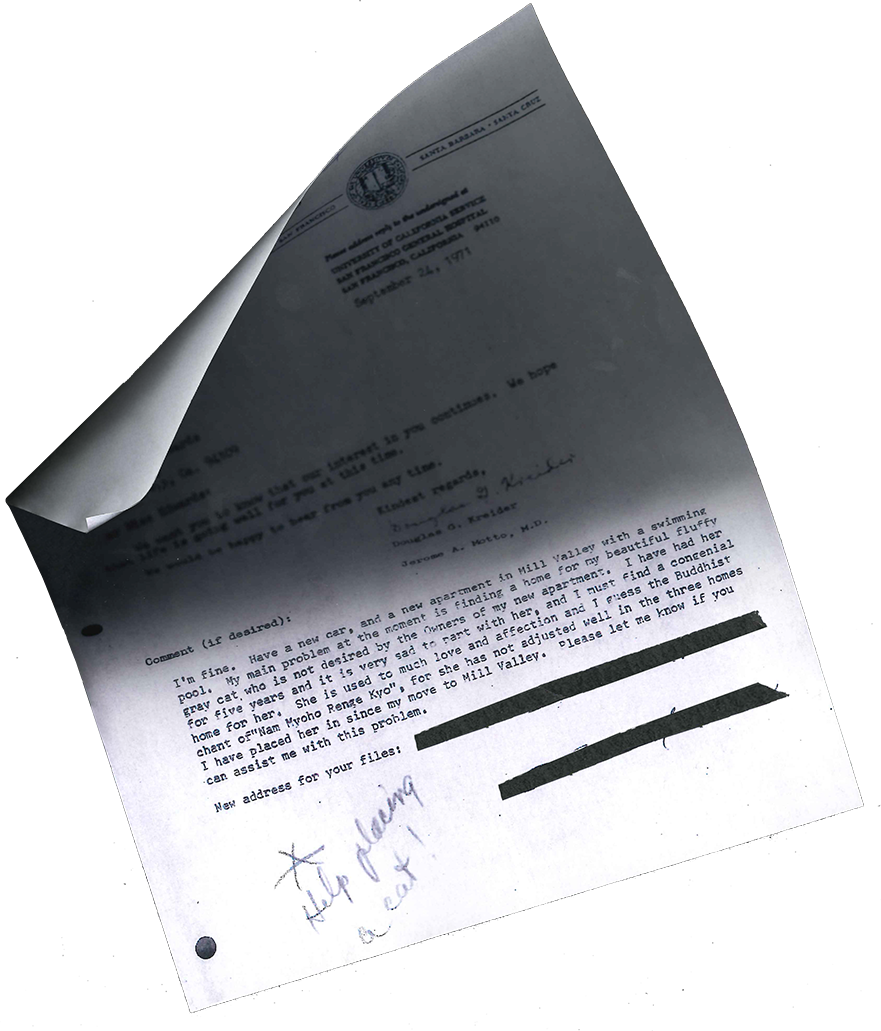

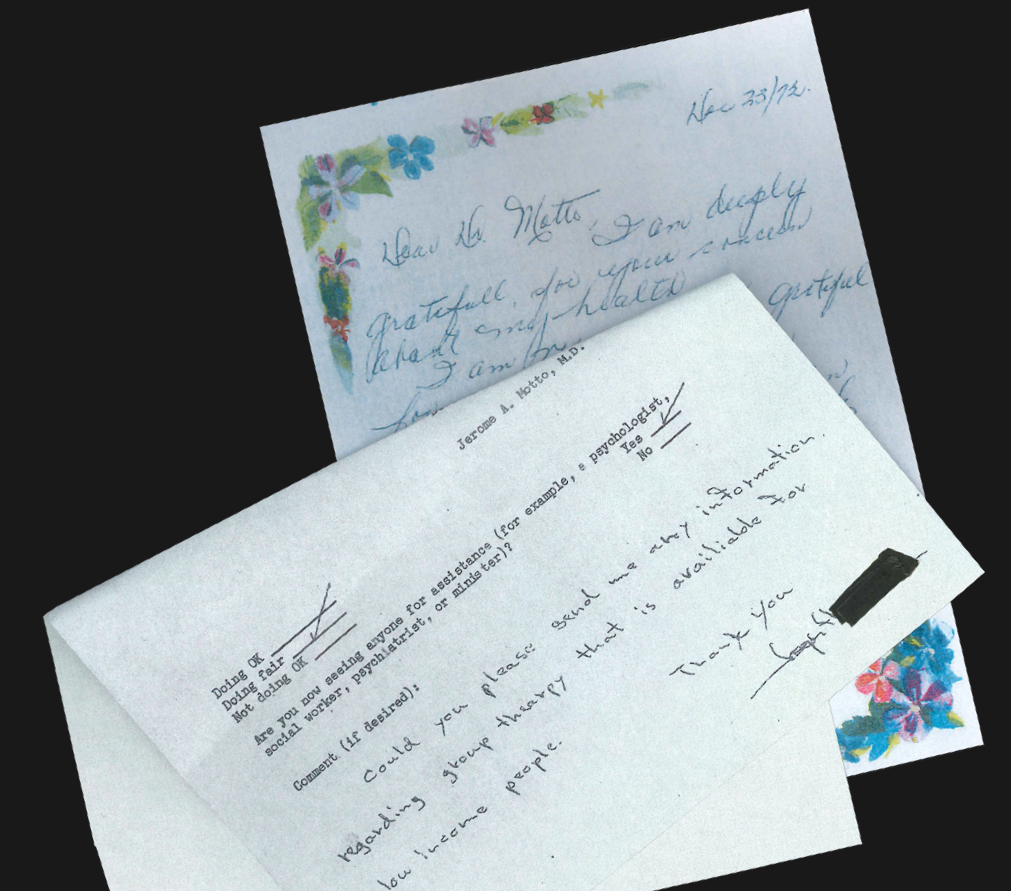

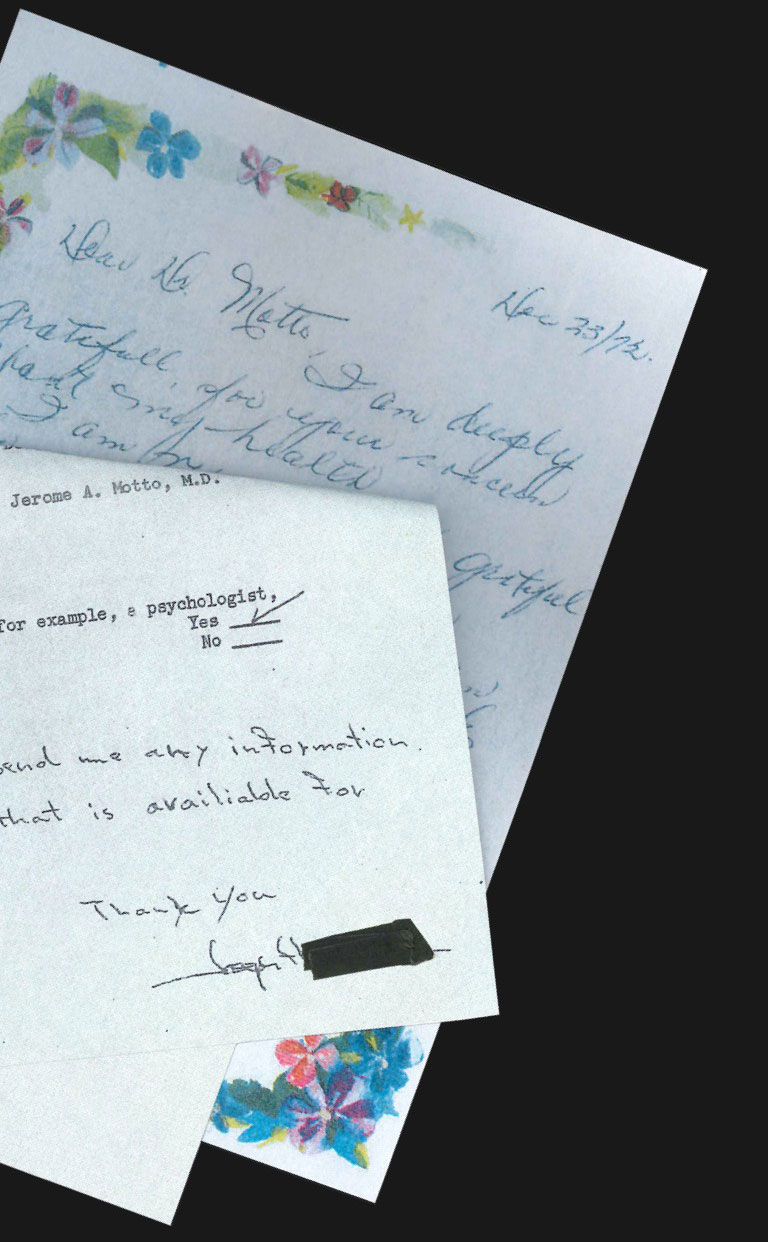

By late 1970, after Conway had left the study to start a family, clues started emerging that Motto’s experiment was working. Patients were finally writing back. Some of their notes were extremely brief; a tidy “I’m fine, thank you”—what Motto liked to call a “kiss-off.” (“Of course, we didn’t leave them alone,” Motto said years later.) Others were more revealing. One patient asked for a prescription for Valium. Another requested help finding a home for her fluffy gray cat. A young man feared being shipped off to Vietnam and hoped that Motto’s team could send the Army a letter confirming his previous hospitalization. “I would rather take my own life than destroy another’s,” he wrote. One person, who had survived a jump from the Golden Gate Bridge, sent a letter in which every sentence began with the letter p.

Motto recalled receiving letters that thanked him and his team for remembering them, while one replied, “You will never know what your little notes mean to me.” Even when the subject matter was dark—“Please call I don’t care what time it is. I love my kids but I need a rest because I think I am having a nervous breakdown,” a woman wrote in 1973—there was a sense of intimacy there.

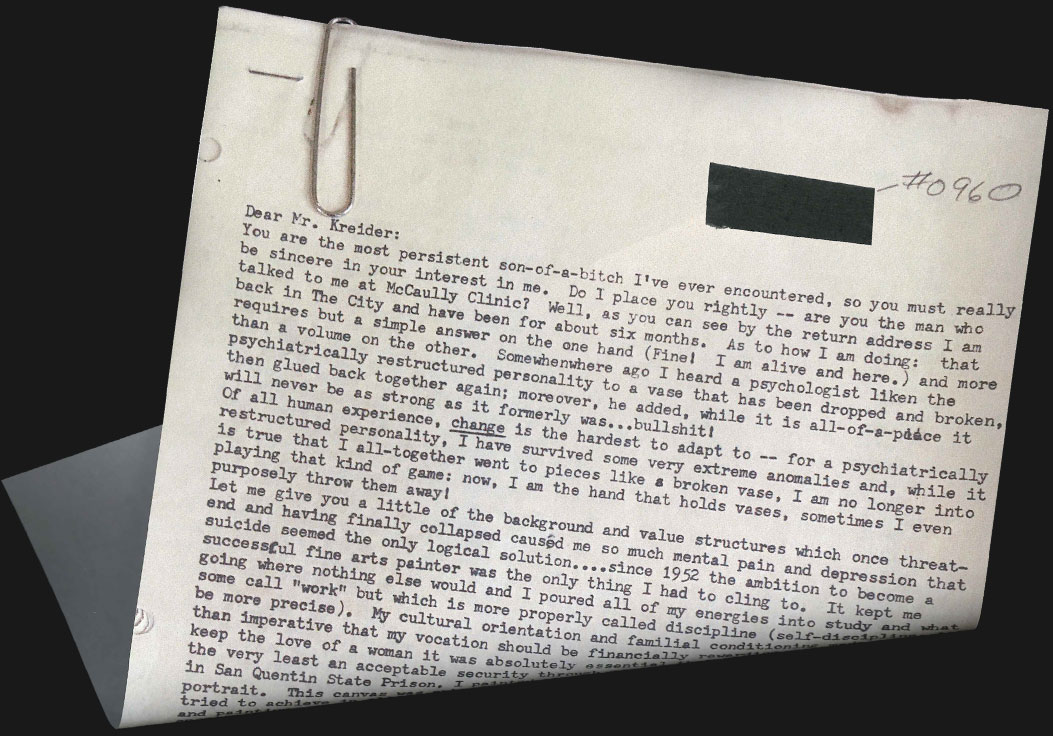

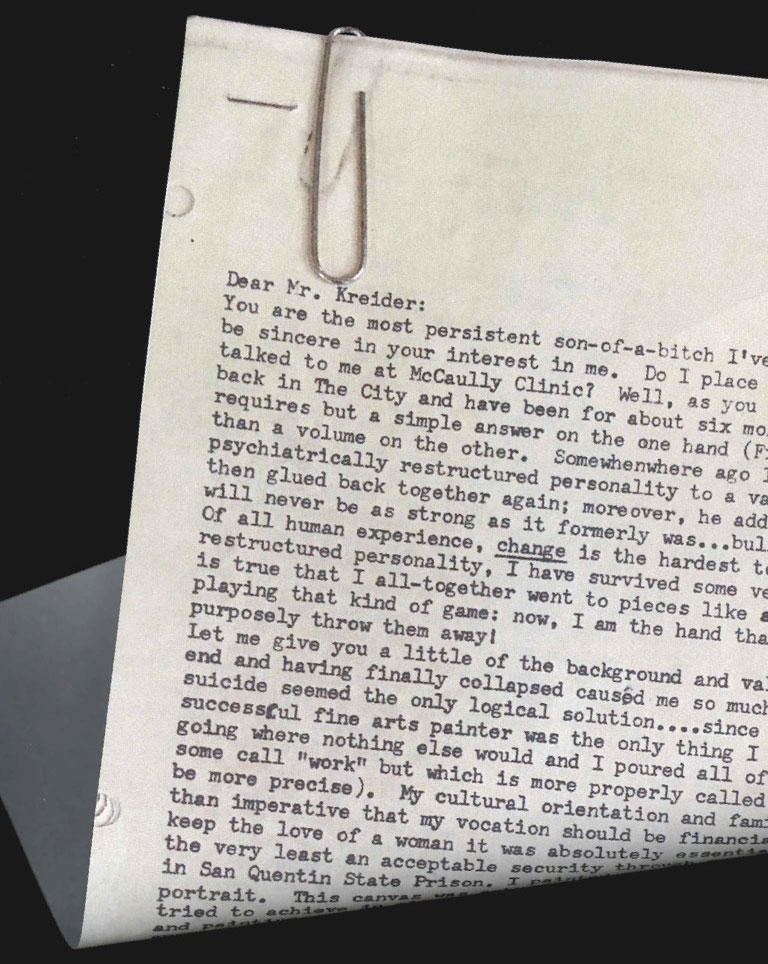

The most pivotal response was sent to Douglas Kreider, one of Motto’s researchers, by a study participant who lived in an apartment in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. The man, who 18 months earlier had written a “kiss-off” letter, now described himself as a broken vase held together by his own hands. His letter spanned five single-spaced typed pages and read as if it had taken days to write. Forty years later, Motto could remember the first sentence: “You are the most persistent son-of-a-bitch I’ve ever encountered, so you must really be sincere in your interest in me.” There it was, a perfect encapsulation of the study’s aims. Motto called it “the bingo letter.”

Still, as promising as these replies were, they were just anecdotal evidence. For solid proof, Motto would pile a few researchers into his station wagon about once a year and drive an hour and a half northeast to Sacramento. They would arrive at the Department of Public Health at 8 in the morning and review the state’s death records, staying until they had looked up the names of every single study participant. They wanted to see if any of them had died by suicide.

“It was kind of a solemn duty,” Kreider said. “There was an undertone of ‘I hope I don’t discover something about someone I know.’” On one occasion, he did. He, like so many of the other researchers, had made real connections with his patients. This one was close to his age. The man had trouble making eye contact and suffered from paranoia. Kreider remembers that no one talked much on the rides home from Sacramento.

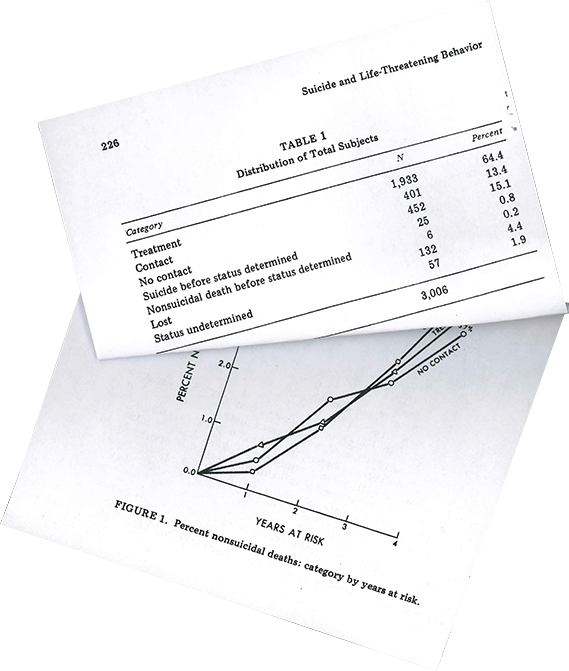

After about four years of these trips, Motto and his team had enough data to determine that their work was unprecedented in the history of suicide research. In the first two years following hospitalization, the suicide rate of the control group was nearly twice as high as that of the contact group. And it wasn’t only that no other experiment had ever been able to show a reduction in suicide deaths. Motto had also demonstrated something more profound: People who attempted suicide and wanted nothing to do with the mental health system could still be reached.

When Motto released his data in 1976, the field of suicidology was still very small and very new. The results were published in the country’s only journal dedicated to suicide research—circulation: 1,002—and his remarkable finding was mostly ignored. Still, Motto kept on with the study; his team sent out letters for nearly the rest of the decade and continued to track outcomes for each participant for 15 years. In an updated report on his findings, Motto showed that those who received letters continued to have slightly lower suicide rates for years—even as the letters decreased in frequency and then stopped altogether.

Motto didn’t do much to hype his achievement beyond speaking to small crowds at conferences and award ceremonies. In his quiet way, he was pleased that his work had meant something, and he turned to other projects. He continued to teach and publish articles. He advocated tirelessly for suicide barriers to be erected on the Golden Gate Bridge.

And Motto held on to people. Every day, he called his sister Sandy, the one who had gone through a divorce during the war. Long after his retirement, and even when he was basically deaf, he allowed a few former patients to call him regularly. “Some of my most prominent memories,” his son Josh said, “are of Christmas Day or Christmas Eve. The phone would ring, and he would go upstairs and be gone for an hour.” The act of listening was sacred to him. It was what made Motto feel most alive—to ask: Tell me more.

A psychiatrist once asked Motto, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” Motto replied, “No, you aren’t, but you are your brother’s brother.”

He seemed never to stop, even when his posture began to stoop and his office had turned into a labyrinth constructed of towers of academic papers and yellowing books, overlooking the pool he never used and the garage filled with still more papers and books. And tucked right there within a folder among his files was the bingo letter, which he kept in mint condition until the day he died, waiting to be rediscovered.

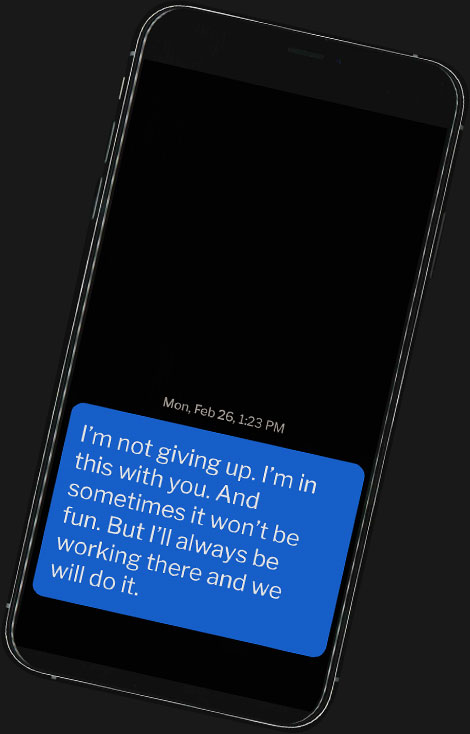

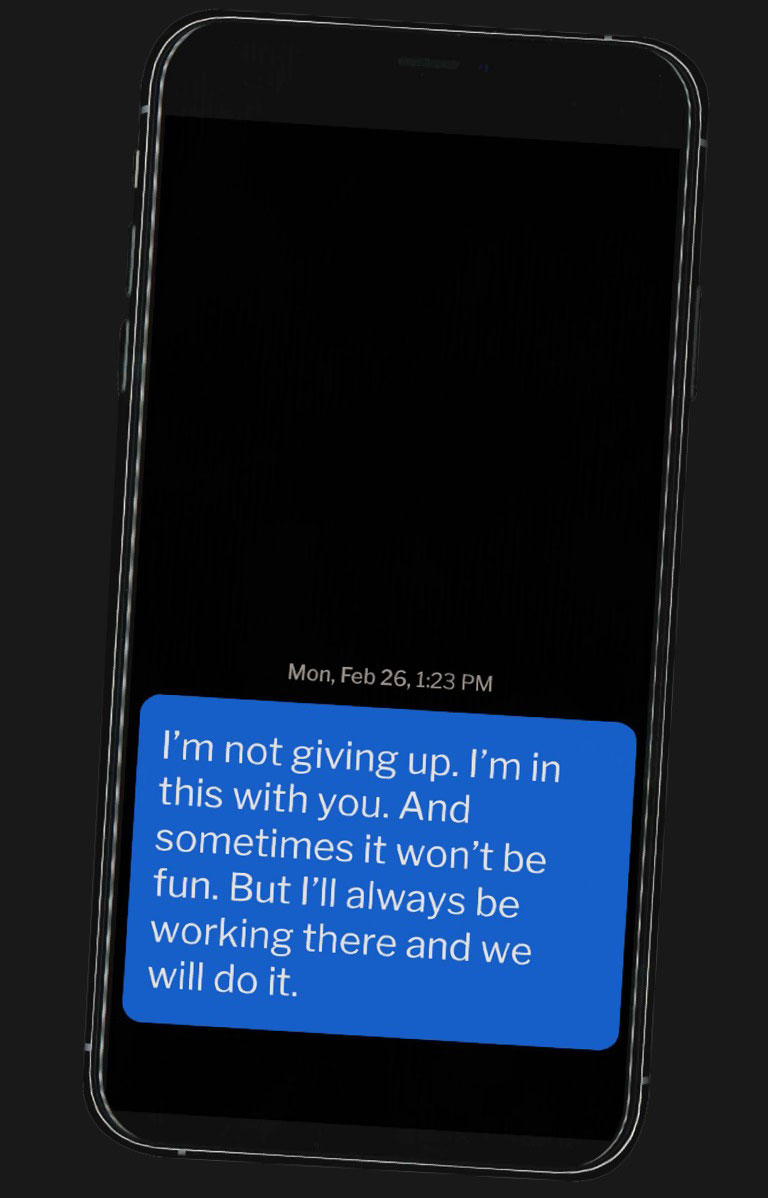

Ursula Whiteside is, above all else, a bad pun and cat-based humor kind of person. She seems never to have met a GIF of a penguin, or of Beyoncé, she didn’t like. And her therapeutic practice draws heavily on these cornball ways. One of her clients had trouble getting out of bed in the morning, so Whiteside regularly texted her things like: “Here comes the magical wake up goat to make this day less baaahhh.” And the next morning: “The rabbit needs feeding! Only you can make this happen by hopping out of bed.” When that same client went on vacation last year, Whiteside sent a text urging her to feel “FREEEEEEEE!” accompanied by a cartoon of a dog sticking his head out the window. (These texts, like all others in the piece, were provided not by Whiteside, but by the patients.)

While her messages don’t mimic Motto’s plainspoken voice, they fully capture the spirit of his work. Whiteside started sending them when she went into private practice four years ago and immediately discovered how powerful they were. So many of her patients struggled between sessions. They bristled at the artificial boundary of a 50-minute conversation. The texts acted like evidence of a relationship, tokens her patients could hold on to as proof someone cared about them. It’s hard to overstate how different this is from the correspondence patients usually receive from the medical establishment. Whiteside has a therapist friend who calls the typical automated notices people get when they miss an appointment “I Hate You Letters.”

Still, Whiteside sets rules for her patients: They must agree to receive the texts. They don’t have to text back. If they do, they need to understand that they might not receive a response for at least an hour. She might be in a session with another client, or on her way to lunch. She also wants her patients to give her clear feedback on what they like and don’t like. One person said she hated the penguin memes and would prefer to receive pictures of nature instead. “You’re always paying attention to what they find funny, to what they are saying when they cry,” Whiteside said.

She sets rules for herself, as well: Typos are OK. Being a little annoying is OK. Each text should take no more than 90 seconds to write, because anything longer might read like it’s been workshopped too much, not enough like a message between friends. She also makes sure to time her texts so they don’t arrive only when patients are in crisis. Mostly, they should appear for no particular reason. She had been thinking about them, that’s all.

“I think people die when they feel completely alone,” Whiteside explained.

By the time she developed her sense of mission, a small band of therapists and researchers from all over the world had also recognized the value of Motto’s approach. Gregory Carter, who ran a psychiatry service in New South Wales, Australia, orchestrated a study in which Motto’s words were typed onto a postcard illustrated with a cartoon dog clutching an envelope in its mouth. The notes were sent eight times over the course of 12 months to patients who were among the hardest to treat. The majority had histories of trauma, including rape and molestation. Some had made repeated suicide attempts. But Carter found there was a 50 percent reduction in attempts by those who received the postcards. When he checked in on the study’s participants five years later, the letters’ effects were still strong. And the cost per patient was a little over $11.

In Tehran, researchers ran a similar experiment, tweaked to fit the local culture. “In my mind, [the Motto text] was maybe boring for our patients,” said Hossein Hassanian-Moghaddam, an associate professor at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. “Maybe you think that it is somehow a robot that is sending you this kind of message.” Instead, the Iranians wrote sentimental greeting cards packed with inspirational sayings or religious text. Some were inscribed with quotes from Albert Einstein. Others drew from Buddha or President John F. Kennedy. They also sent cards on the patients’ birthdays (a favorite among the participants). The results were similarly positive.

Kate Comtois, a renowned suicide researcher based in Seattle, sought to test these methods out on a new audience—one close to Motto’s heart. For her randomized control trial, funded by the Department of Defense, she and her team sent out text messages to hundreds of active duty Army soldiers and Marines. Each one got 11 Motto-style texts throughout the course of a year.

When the researchers focus-grouped the messages on active-duty servicemembers, they were told that for this to work on Marines, texts should never imply weakness. “We were schooled,” Comtois said. “They didn’t want us to use the word ‘need.’”

So she and her team kept the texts to the point: “hope life is treating you well” and “hope all’s well and you’re taking good care of yourself.” Because they were texts, the researchers could reply to the soldiers with emoticons or whatever else felt natural. The study, which recently concluded, showed that recipients were less likely to have suicidal thoughts or make an attempt. Comtois was struck by how different the text interactions felt. “Most of the time we were reaching out to somebody who was happy to hear from us,” she said. “That’s just not how suicide care is.”

But perhaps the most ambitious Motto-related work taking place right now can be found in a small mental health clinic in Bern, Switzerland. One of the clinic’s co-founders, Konrad Michel, centered his entire approach around patients’ storytelling. He initially recorded his therapy sessions with patients and then had them reflect on the experience in filmed follow-up interviews conducted by a colleague. They told him what they thought of his questions, his mannerisms, the way he made them feel. The work was humbling.

Over time, he and the clinic’s other co-founder, Anja Gysin-Maillart, developed a new therapeutic model called the Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program, or ASSIP. It’s a far more intense and compassionate way of treating the suicidal—an add-on to regular therapy and medications. In the first session, which lasts about an hour, a patient is recorded telling the story of a suicide attempt and what led up to it while a therapist tries not to influence the narrative. In the next session, the same therapist sits with the patient as they watch the recording together. The therapist hits “pause” whenever there is an opportunity to dig deeper, searching for breakthroughs. In the third session, they outline potential triggers and vulnerabilities that could lead the patient back into a suicidal mode. Then they jointly plan long-term goals and strategies that minimize the risk of another attempt. If a fourth session is needed, they’ll watch the recording of the first session again and tweak the safety plan to fit the patient’s needs.

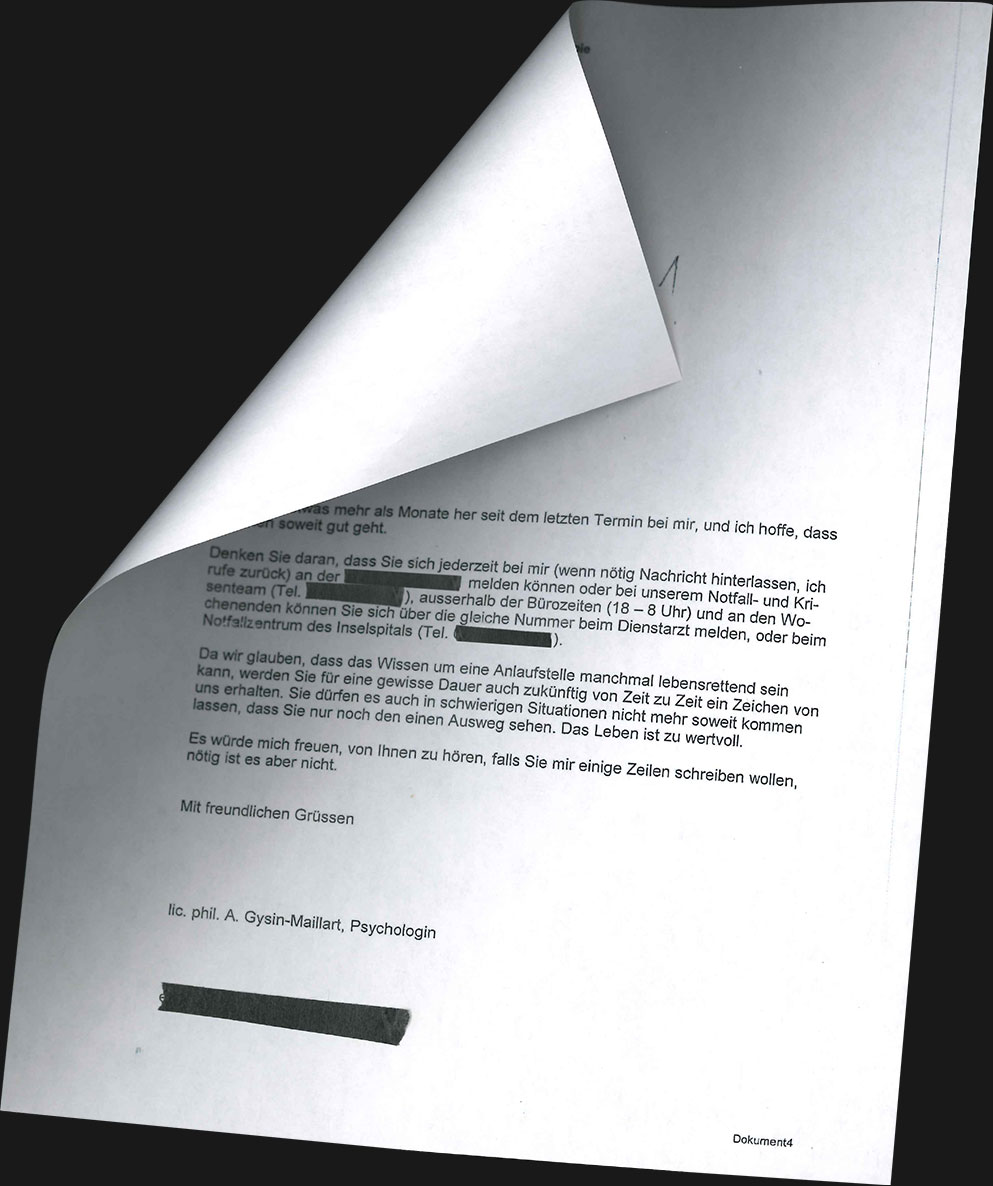

The work, Gysin-Maillart says, brings clarity to patients, who often feel overwhelmed after an attempt. And if it all seems dramatic, that’s the point. The therapist and the patient are expected to bond over the experience. The patient then receives Bern’s version of a Motto letter at regular intervals for two years.

So far, the outcomes have been astounding: In 2016, the findings of a clinical trial were published, showing an 80 percent reduction in the risk of attempts and fewer costly days in hospitals following treatments. New clinics have been set up in nearby Zurich, as well as in Finland, Sweden and Lithuania. Late last year, Michel began training therapists in Syracuse, New York, to start their own practice with federal funding.

When I visited the clinic in Bern, I was more interested in what I didn’t see. There were no doctors giving patients a diagnosis or prescribing them medications. Instead, it was a place of vigilant listening. I watched a first session between Gysin-Maillart and a patient with a long, complex history of suicide attempts. Gysin-Maillart asked what had led her to consider suicide as an option. And for the next 25 minutes, she listened without a single interruption. “Did you have the impression that I disappeared?” Gysin-Maillart asked me afterwards. She worried that her body language was too much, especially her head nods. “It’s best not to nod,” she said. “But her story was so hard I had to give her something back.”

Several of her patients told me that unlike other doctors, Gysin-Maillart never tried to assess their risk. Instead, she made them feel understood and hopeful. Watching themselves on the videos helped them understand the severity of what they had been through. They couldn’t minimize what they had done. And the letters only solidified their sense of connection to her.

Of all the patients I met, no one seemed as invested in the letters as a college student named Anna, who told me that before coming to the clinic she had felt “very lost in the world.” Her replies to Gysin-Maillart ended up taking the form of long confessionals, filled with details about her life that she hadn’t shared with her therapist (whom she admired) or her mother (with whom she was on good terms). Anna came to see Gysin-Maillart as the keeper of all her secrets.

“I got your letter and almost didn’t want to open it, because I wanted to preserve that feeling of joy a little while,” Anna replied after Gysin-Maillart’s first note. “Like when I don’t open a present right away.”

For the next two years, Anna wrote Gysin-Maillart about how hard it was to fit back in following her attempt, how even her friends didn’t understand her and why she couldn’t cry. To cope, she had taken up rowing. “Rowing on the Rhine,” she wrote, “when everything is still quiet and undisturbed, and the fog drifts over the water, and the sun slowly begins to warm up, the quiet slap of the oars and the rush of the water around me, that gives me an indescribable feeling.”

Three months after receiving her last letter from the clinic, Anna’s insomnia was raging and she started thinking about suicide again. So she took what she’d learned from her sessions and began writing an email to Gysin-Maillart. Just as she had in previous letters, she poured out all of her thoughts. But when she was done, she realized she didn’t need to send it. Writing it was enough.

The Motto approach is like a promising experimental cancer drug. It has the power to send suicidal urges into remission or reduce them to a manageable level. It is the best hope for some of society’s most despondent people. But that doesn’t mean therapists are eager to try it or that it’s easy to scale up, particularly within a health care system as downright messy as ours.

April Foreman, an executive board member of the American Association of Suicidology, uses the term “virtue theater” to describe the current state of mental health care in America. It outwardly signals hope, but on the inside, clinic personnel are consumed by paperwork, funding stress, liability concerns, impossible caseloads and the ever-changing and byzantine ways people qualify for help. “We train mental health professionals to be terrified of all things,” she said. The job becomes about avoiding litigation and high-risk patients, not experimenting with new ways of treating the people who need it most.

This helps explain why insurance companies have yet to embrace Motto’s methods. The industry has a long history of not wanting to pay for mental health services, too often covering them only when required to do so. Up until about a decade ago, strict limits on treatments were the norm; only a relatively small number of therapy visits were covered per year. The financial incentives are still out of whack today. Insurers pay therapists the same rates whether they’re seeing a mildly depressed 20-something or a chronically suicidal 50-year-old with an opioid problem and a gun in his nightstand. As a result, solo practitioners may be less likely to accept clients with a history of suicide attempts. Without additional grant money, many hospitals and clinics aren’t inclined to devote resources to an intervention they can’t reimburse for.

Even more frustrating is that there are plenty of people within the insurance industry who know how powerful the Motto approach can be. A medical director at Cigna admitted to me that he “absolutely” believes in it, while one from Premera Blue Cross deemed it “incredibly valuable.” The Premera director told me that she sends messages to clients in her private practice, but couldn’t see her company ever reimbursing people for individual texts or emails.

That’s not to say that the Motto approach doesn’t come with real risks. The idea of having to defend penguin GIFs in a wrongful death lawsuit is genuinely frightening. And because of privacy concerns, many hospitals and clinics do not allow their doctors to communicate with patients outside secure portals. If the contents of these conversations were hacked and made public, it could be catastrophic for everyone involved. Some therapists even expressed concern that a spouse could see the messages and believe them to be evidence of an affair.

And then there’s the difficulty of writing the messages themselves. Think of all the times a text of yours didn’t land just right and you had to respond explaining that, No, what I really meant was this. Or the instances when you couldn’t decipher whether a sarcastic message from a partner was playful or taking a subtle dig at your personality, so you just sat there stewing for a while. Then imagine that interaction taking place when somebody’s life is at stake.

These kinds of issues become harder to manage at the institutional level. Kate Comtois, who oversaw the successful military study, said that with so many therapists untrained in how to treat attempt survivors, it may be difficult to handle a wave of patients if they seek help after receiving a caring letter or text. And writing the letters can be tricky at scale. When the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs first encouraged its facilities to send out cards to ailing vets, nobody imposed specific language, and many of the messages ended up straying from the therapeutic ideal. Some bugged patients about not answering the phone when a therapist called; others pestered them to eat better. They asked too much in return from the patients (breaking Motto’s rule) and, just as bad, they expressed worry. Worry, Linehan told me, sends the wrong message because it’s “a statement that you don’t really believe in them.”

But perhaps the biggest obstacle preventing the Motto approach from becoming more universal is that it crosses one of the most inviolable lines in therapy: the one between in session and out. From the beginning of medical school, doctors are instructed to keep an emotional distance from their patients to prevent burnout and guard their objectivity. Psychologists and social workers are taught similar principles. Basically, when the work day is over, you leave your patients’ struggles behind and return to your own life. There’s a reason a therapist’s voicemail message tells patients to call a suicide hotline or 911 if they’re in crisis after hours.

Paul Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry, medicine and law at Columbia University, believes that texts are dangerous because they can be “the first step to the crossing of other boundaries.” He mused: “Is this once a day? Every hour? Can you have a drink even if that means you might not be as sharp? Can you enjoy a family wedding without retreating to a corner to answer text messages?”

At least one study cuts against these concerns. In 2004, researchers found that the more open therapists were to receiving calls from clients in between sessions, the fewer they ended up taking. Stacey Freedenthal, a clinical social worker and associate professor at the University of Denver, believes that one way to manage the boundary problem is for all mental health care workers to have a better understanding of risk. Therapists need to be able to differentiate between acutely suicidal patients (those who are in danger right now) and people who have contemplated suicide for years but who often do not intend to act on those thoughts.

Everyone in mental health, she said, should know how to treat the acutely suicidal—to develop a plan to keep them safe, to talk to family members about getting a gun out of the house. It’s akin to every doctor knowing CPR. But she thinks that therapists who don’t believe they’re emotionally adept enough to handle the chronically suicidal should get training when they take on that responsibility. “Some therapists stand in the light and call out to the person in the darkness, ‘Come out, there’s light here, there’s hope here,’” she says. “But sometimes what the suicidal person needs is for the therapist to join them in the darkness and show them a way out.”

On a sunny June morning, I made my way to Whiteside’s modest postwar bungalow in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle so that I could see what a normal day looked like for her. I knew she’d have sessions with clients and paperwork to churn through, but I was most interested in what happened during the in-between times.

She arrived at the door full of energy, her face elastic and expressive. The living room was a hodgepodge of thrift-store furniture, and she apologized for the walls being mostly bare. The two picture frames sitting on the dark wood coffee table both contained stock photos of smiling models. She’d lived here for more than a year but hadn’t found time to replace them with pictures of her own. In her kitchen cabinets, she had stored research files among the pots and pans.

Whiteside cocooned herself inside a fuzzy red blanket on her sofa and decided to check back in with Mary, one of her regulars. Whiteside has about 10 patients at a given time, and she worries most about the ones who aren’t texting or calling. She hadn’t heard from Mary in a couple days.

Mary (not her real name) was 41 at the time, with a good job in a nearby school system, and she worked very hard to hide her thoughts of suicide from friends and co-workers. But at night, she had trouble staying off gun websites. She had run through dozens of medications and several psychiatrists over the years. She told me she saw Whiteside as her last chance at getting better. Still, many of their sessions hadn’t been easy, and Mary would leave therapy angry about all the emotional work Whiteside required. She set up a ring tone to alert her when Whiteside sent a text because there were times she couldn’t look at it until she was ready.

It had been Mary’s birthday the day before, and Whiteside wasn’t sure how she’d handled it. She’d sent Mary a text before I arrived—just a jokey meme from “The Shining” in which a cat (instead of Jack Nicholson) breaks down the bathroom door with an ax. Whiteside was fully aware that Mary hated cat humor, but these texts had become in-jokes between them.

“As I was sending it, I was like, is this going to be harmful? Could this be interpreted another way?” she said. At first, she didn’t expect a reply. Now, hours later, she was craving one.

Whiteside sat still on the couch for nearly a minute, blinking at her phone. She wasn’t sure what to text, or if to text. Maybe she should sound a little scared. Maybe she shouldn’t. She started playing with language, saying words out loud to test their weight.

“Did you do anything for your birthday?”

No, that wasn’t right. Too judge-y. She was silent for another minute. She picked up her phone. She checked Facebook. Still no message from Mary.

“Did you do anything for yourself for your birthday?”

A short pause. Yes, she liked that one. The message might have seemed innocuous. But for someone like Mary who could isolate herself, it carried a subtle reminder of a therapeutic goal: learning always to be conscious of your state of mind, to anticipate and head off destructive thinking. For yourself, the message said. Maybe she’d get it. Whiteside tapped it out quickly and hit send.

About five minutes later, Mary responded that she was OK, but offered no further details. Maybe the exchange annoyed her; maybe it didn’t. Either way, she had responded with something warmer than silence.

The episode was both a success and a perfect case study of why therapists who don’t possess Whiteside’s superhuman patience can struggle with the Motto approach. Treating the suicidal means that your clients are never far from your mind. You have to be an expert at interpreting their messages and noticing troublesome shifts in personality that are imperceptible to just about everyone else. For years, Whiteside has excused herself from dinner dates to soothe clients. She leaves her phone on at the movies and when she boards planes. She knows—and her friends agree—that she doesn’t do enough for herself.

But she finds herself more at peace when she’s in regular communication with her clients. The people who create the most stress for their therapists are the ones who don’t engage at all. The people who talk about their pain, on the other hand, are extending an invitation to help. Shortly before I visited her, Whiteside was about to fly home from San Francisco when she received a text. “I do not want to be here. I do not want to breathe. I do not want to talk,” a client wrote her. This middle-aged single mother had been drinking and then heard a song that reminded her of an old boyfriend. She was spiraling. But Whiteside knew precisely how to defuse the situation. “OK, now time to get ready for bed,” she texted after some back-and-forth. “Lots of water. Comfy pajamas.”

The client followed the instructions, and the next morning, she texted Whiteside her plan to get through the rest of the week, adding, “I know the first step was to get me through last night. We did that.”

Only rarely has Whiteside ever buckled from the demands of her approach. In 2017, she was going through a rough patch on a research project, and although she kept her appointments with Mary, she stopped sending text messages between sessions for a week and skipped two weekends. When she started to feel guilty, she asked herself how many doctors texted their clients on their days off. All of a sudden, she felt like an outlier; perhaps her entire method was risky.

At their next session, Mary brought up the lack of communication, worrying that their relationship had hit a snag. “I don’t want to interrupt your week…” Whiteside began to explain. Mary’s reply was quick and firm. “No, no, no, no, no, no. Don’t stop,” she told her. “Don’t stop.”

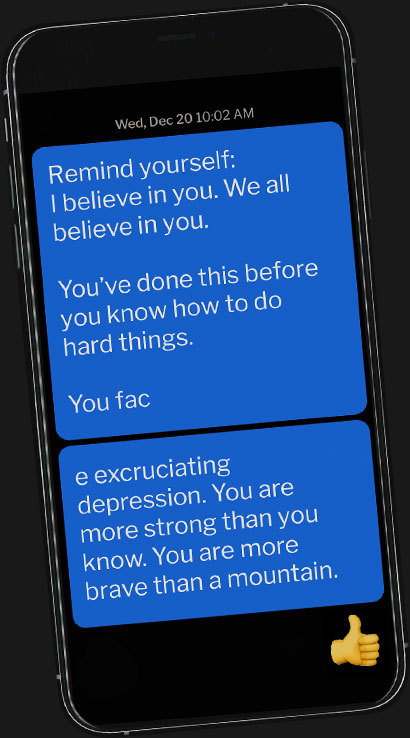

Over time, Mary has built up a support system and finally feels comfortable enough to go to softball games with friends or on trips to see her family. She also no longer feels unworthy of Whiteside’s attention. And yet, she still has days when she plays with the idea of “maybe just getting it out of the way now.” On the morning before a new round of electroconvulsive therapy, Mary was feeling particularly depressed and afraid. But there was Whiteside again, popping up on her phone. “Remind yourself: I believe in you,” Whiteside texted. “You’ve done this before. You know how to do very hard things.” Suddenly, Mary felt fortified.

On another bad night, Mary made a scrapbook of some of her favorite things in the world. Along with pictures of her nieces and nephew and a photograph of a shimmering pool, she pasted screenshots of a few texts from Whiteside. Yeah, some of them were corny. (“Wouldn’t it be nice if black clouds offered sprinkles?”) But Mary was in awe of them because they worked.

Whiteside would quibble with that. She’d say they are working for now. “Caring messages are a nice acceptance bath, and that’s great and often what’s needed first,” she told me. “But then the person needs support in actually changing, otherwise they end up staying in hell.” Too often in suicide care, that support simply doesn’t exist. It’s not like when you’re diagnosed with cancer and are introduced to a team of caregivers: oncologists, surgeons, pain specialists, nutritionists, even wig experts. Suicide treatment is a far lonelier enterprise. Most of the time, it’s just two people, talking back and forth, trying to figure out what it takes to keep living.

Whiteside will never fully know what’s in her patients’ minds. She’ll always worry that she won’t be able to reach them in the moment they need her help the most. All she can do is send out a message and hope.

A few days after my visit to Whiteside’s house, I met Amanda, the nurse who swallowed all those pills a decade ago. She showed up in the fading light of rush hour in front of Whiteside’s office building and greeted me in a library voice so slight I could barely hear her. Although she stopped seeing Whiteside around two years after that attempt, they stayed in touch and had agreed to meet me so that we could review their years of correspondence.

The building’s other tenants had gone home for the evening, leaving it dark and quiet inside. It felt almost as if we shouldn’t be there. To put us at ease, Whiteside phoned the bar across the street to order a hummus plate and a six-pack of root beer. As we waited for the food, I asked Amanda about her first impression of Whiteside.

“I thought she was naïve,” she said. “Everybody else I’d worked with seemed overwhelmed and scared and frustrated. … I always worried that I was too much.”

“I understood that you felt like you were too much,” Whiteside replied. “I think if it was anything, I doubted my abilities.”

Suicide “always felt like my problem,” Amanda said. “Everybody blamed me and I needed to fix it.”

“Do you think that you could feel that I cared about you, though? Or were you not able to believe it?”

Amanda considered the question. The only sound in the room was the cord from the blinds clicking against the window. A full 15 seconds went by.

“I thought that you cared about me as much as a provider was allowed to care for their client,” Amanda said.

“Did that ever change? Or was that…” Whiteside stopped herself. “You can definitely say ‘no.’”

“I think in my head I just had to keep thinking, ‘She’s not my friend, she’s my therapist,’” Amanda said. “I think it would have made it harder if I felt like there wasn’t a boundary.”

Eventually, they made their way to the early morning of September 28, 2007, and their last exchange before Amanda’s suicide attempt. Whiteside reviewed her old email with embarrassment. Read aloud, the words now seemed harsh and demanding. Motto wouldn’t have approved. “Take a hope pill,” she had written, reinforcing a theme of theirs from therapy. “I need you to make a specific plan for this weekend.”

Whiteside started rewriting on the spot, testing it out on Amanda. “If I were to do it over again, I might say, ‘Listen, Amanda, I need you to hear me right now. I can feel your suffering through this email. And I want you to know that I am really—literally—holding on to you. And you can’t leave,’” Whiteside said. She paused. After what seemed like a long while, she thought of a last line, one that possibly could have kept Amanda on the hook: “And can we talk at your lunch break?”

For a moment, Amanda was silent, then tears began to slide down her cheeks. She just wasn’t sure. She thought maybe nothing would have stopped her, but there was no way to know after all this time.

About a year later, I called Amanda up, and she told me something about her attempt that she’d never told anyone before. It now seemed significant to her that after picking up the pills, she’d waited for hours before she took them. Maybe she was wavering. Maybe she was waiting for someone to reach out to her with just the right words. “I don’t know if I set it in stone,” she said. “I think I could have changed my mind.” There was still a chance.

If you or someone you know needs help, call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. You can also text HOME to 741-741 for free, 24-hour support from the Crisis Text Line. Outside of the U.S., please visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention for a database of resources.

And if you’d like to use the treatment methods described in the piece, check out a nonprofit that Whiteside founded called Now Matters Now. The site teaches basic DBT skills and provides a sample Motto-style card anyone can download and send to someone in need.