HIS

FAITH IN

HIMSELF AND HIS CITY LOST,

JEDIDIAH BROWN DROVE OFF THE CURB OF

LAKE SHORE DRIVE, RATTLED DOWN A SET OF STAIRS

AND BRAKED FEET FROM THE DROP INTO LAKE MICHIGAN.

Jedidiah Brown drove off the curb of Lake Shore Drive, rattled down a set of stairs and braked feet from the drop into Lake Michigan. It was a warm Sunday this February, and the afternoon tourists and joggers across from Grant Park kept moving around the vehicle in their midst. Alone inside his car, Jedidiah wept. On the phone docked to his dashboard, the 30-year-old Chicago activist and Baptist minister set a gospel song to repeat and started recording on Facebook Live. He begged forgiveness for giving up and cursed the city that he loved but had robbed him of everything. “Every relationship I had, I lost it because I was too busy fighting for y’all,” he sobbed. “I’ve only lost because of y’all.” Then he pressed a Glock 19 to his temple.

The concentric neighborhoods around the city center were prospering like never before. But Jedidiah had spent the last decade in that other Chicago, far beyond the Loop. In African-American communities battered by violence and joblessness and disrepute, he showed up at hundreds of crime scenes. He assisted grieving families, raised funds for funerals and negotiated with warring corner gangs to avert reprisals. He filled his rented apartment on the South Side with young people in need of shelter. On Sundays, 50 members of his church, Chosen Generation, crowded into a nearby commercial space to hear him preach. Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Bernie Sanders and the Obama administration have all sought out his insights and influence.

Jedidiah has a long, muscular face, with wide-set eyes that turn fierce when his brows tighten. Short and lean with a clean-shaven head, he bears himself as if he’s a much larger man. In conversations, he listens with a stern intensity, but he has a laugh like a car failing to turn over—a nasal gchuhh, gchuhh, gchuhh that invariably sends him stumbling. I first met Jedidiah in the summer of 2014, when he was camping out in the park in front of the DuSable Museum of African American History, near the Obamas’ South Side home. The weekend before, 82 people had been shot and 14 killed in the city, almost all of them in a handful of black neighborhoods. That was unacceptable to Jedidiah. He announced that he would sleep in the park until the city delivered the jobs and economic investment needed to stanch the bloodshed. He didn’t own a tent or a generator. He hadn’t figured out where he’d use the bathroom or what might constitute victory. Saul Alinsky he was not. But just as he improvised all his sermons, he believed there was no time to waste mulling over strategy while people suffered.

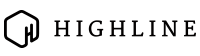

•A dead man in a South Side parking lot; the only supermarket in South Shore before it closed in December 2013.•

We hooked up again last November, in the days after Donald Trump was elected president. Jedidiah has always maintained a quixotic belief in the ideal of the village cooperative, and he’d gone to calm a racial furor in Mount Greenwood, a mostly white enclave on the edge of the black South Side. In my post-election fugue, I tagged along, since Jedidiah looked to be among the few people attempting to straddle the fault lines of the city and the country—divisions that have only become more glaring since. During a unity march he helped organize in Mount Greenwood, Jedidiah was set upon by both crowds of angry white residents and fellow black activists, who castigated him for being too conciliatory. I watched as a hockey mom edged her way politely past neighbors until she reached the police line at a metal barricade. Then she screamed herself hoarse: “How much are you getting paid? Yeah, you, smiley! How many killed in your own neighborhood? Go home!” As if Jedidiah wasn’t home already.

For despite the criticisms of this new generation of young black activists—that they care only about police shootings and not other troubles besetting their communities—Jedidiah was so profoundly invested in his neighborhood that its misfortunes devastated him. “I see lives being destroyed, and I don’t know what to do,” he once told me. “It creates a burden in me, an unrest in my resting. Literally, I lay in my bed and my heart beats so heavy for the city that it drives me to tears.”

This truth is shared by numerous organizers grouped under the Black Lives Matter moniker. Once they raised their voices in protest, they were compelled to do more and more. People looked to them to be social service providers, youth counselors, politicians, economic developers and policy experts on criminal justice, housing, schools and healthcare. A catalogue of impossible jobs, all of them overwhelming and unpaid and carried out on the fly with mostly an absence of mentors.

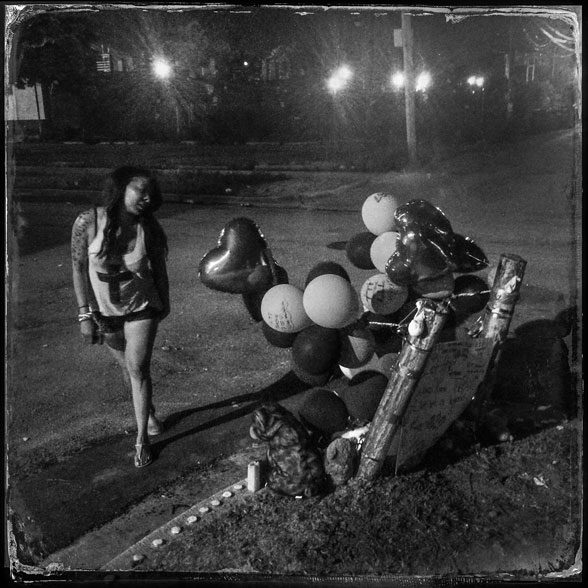

Many of these activists were unprepared for the emotional anguish, the self-recrimination and financial burden, the media spotlight, the attacks from outside and within the movement. Their personal trauma became an unspoken side effect of the work. Edward Crawford, one of the most prominent protesters in Ferguson, Missouri, died this spring from what was believed to be a suicide. Last year in Columbus, a 23-year-old Black Lives Matter activist named MarShawn McCarrel shot himself in the head on the steps of the Ohio statehouse. “I feel like he did so much for so many people that he forgot to take care of himself,” his mother mourned.

“Every activist and organizer I know is traumatized in their own way,” DeRay Mckesson, one of the leading figures of the Black Lives Matter movement, said. “They’ve sacrificed job stability, relationships, educational opportunities to fight against a system that was literally killing people. They’re still processing those sacrifices. We are young people who are trying to figure out how to build a better world and still be healthy and sane and strong and loving and a partner and a brother and a sister.”

In Chicago, Jedidiah was a hope to mend the riven city, and that made him another one of its casualties. Earlier on that Sunday in February, he had sent me a text that began, “Please make sure you tell my truth Ben. I never took any money or jobs. I really wanted to see a better Chicago for all people.” I didn’t realize it was a suicide note until a mutual friend phoned to tell me about the Facebook Live video while I was at a grocery store with my two children. I drove home with the horrible feed playing in my lap, screaming at the phone for Jedidiah to stop, my kids confused in the backseat. Jedidiah was waving the gun, holding it to his chest and head. Hearts and sad-faced emojis bubbled up over the livestream, the views multiplying to nearly 100,000. It was happening right then, and every unendurable moment looked to be his last. I frantically texted and called. I could hear his phone ringing on the video. “Stop calling me!” he shouted through his tears. So I and probably a hundred other people called him more.

Officers surrounded his car, halting traffic on Lake Shore Drive. At one point, police cruisers rammed Jedidiah on two sides, pinning his vehicle. “Drop your weapon!” the cops ordered. Jedidiah ignored the command. He decided to let them do what too often occurs when the police confronted a black man with a gun. But the officers knew Jedidiah. They’d listened to his demands at protests and watched him on the news; at shooting scenes, they’d sought his help to prevent retaliatory violence. A sergeant kneeled on the ground beside him. Another officer cried, apologizing as he clasped on the cuffs.

• “He was marked by God to be different. He didn’t fit in.” •

Jedidiah was born Darryl Eugene Coleman. Coleman was his mother’s boyfriend’s name. His mother, Ottoweiss Cook, a minister herself, took Jedidiah to a prophetic church when he was 13, and a woman he didn’t know pulled him aside. “God told me to tell you that He’s going to change your name,” she said. Soon after, his mother called him into the living room and there stood a stranger who looked like him. It was his father, Grayling Brown, who said giddily that God had told him he had a son, and God said the son’s name was Jedidiah. The name appears only once in the Old Testament, like an oversight in editing: After David and Bathsheba beget Solomon, the Almighty sends word through a prophet to call the child Jedidiah, which means “beloved of the Lord.” But Solomon he remains. A year later, Jedidiah legally changed his first and last names. “You can’t tell me God isn’t real,” he exclaimed when he recounted this story to me in his kitchen.

Becoming a new person in his mid-teens was difficult. “My entire life, I felt unloved and misunderstood, and I felt a purpose at the same time, like I could make a difference,” he told me. He was always an outsider, even to himself. There was that “duality,” he said. He grew up on the South Side, but his mother, wanting better for him, insisted he attend schools in the suburbs, and he never once went to the same school two years in a row. He carried a briefcase with a coded lock on it, and with great formality each day he’d undo the clasps and pull out the homework he hadn’t even attempted.

A perennial new kid, Jedidiah made few close friends and fought often. He brought home classmates who were outsiders like himself and took in homeless people, expecting his mother, step-father and their church members to help feed and care for them. “He was marked by God to be different. He didn’t fit in,” his mother told me. As a teenager, Jedidiah stood on the guardrail of a bridge, considering whether to leap. The police chased him from the ledge, jolting him with a Taser. He said a doctor at the hospital cautioned him that he was taking on too much.

“I thought I was a joke between God and Jesus, here for sport,” Jedidiah said. “I was the anti-Christ, the worst human being possible. Then I decided God kept me for a reason. I had the ability to help because I saw things others couldn’t see. I told people, ‘I am as flawed as you.’” After high school, he ran a successful program serving 150 youth in an all-black suburb south of Chicago. He was ordained, and people from the suburb followed him to the South Side when he established his church.

In his teens, he also began to help take care of his first cousin’s baby, a boy 16 years his junior named Travis. “He was technically my cousin, raised as my nephew, but he became my son,” Jedidiah explained, realizing that what was normal for him might not make sense to me. Travis, he said, had a wisdom about him even as a small child, an openness and honesty. “That kid is unreal,” Jedidiah said. “He’s been here before.”

• JEDIDIAH AND TRAVIS •COURTESY OF JEDIDIAH BROWN

• JEDIDIAH AND TRAVIS •COURTESY OF JEDIDIAH BROWN

Jedidiah rented a two-story building along a business corridor where many of the storefronts no longer housed businesses. He lived in the apartment upstairs, with young people laid out everywhere, and used the commercial space below for church services. In 2014, he started an organization called Young Leaders Alliance, which he headquartered in the storefront as well. Many African Americans had moved out of the city, a quarter-million since 2000, leaving communities on the South and West Sides that were even poorer and more perilous than before. Jedidiah made a point of getting to know the teenagers who idled on corners, but too frequently he ended up seeing one of their bodies splayed on the concrete fringed by yellow police tape. This was the spring of 2014, still months before a police officer killed Michael Brown in Ferguson and the first large wave of organizing under the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag.

Jedidiah didn’t have a background in organizing. He didn’t know how to run Young Leaders Alliance, especially as people contacted him on Facebook, asking to start chapters across the city and in other states. But he told me that when he sought guidance from an older guard of black activists—civil rights leaders, the heads of churches, black nationalists—they rebuffed him. He was told he had to earn the right to organize in Chicago.

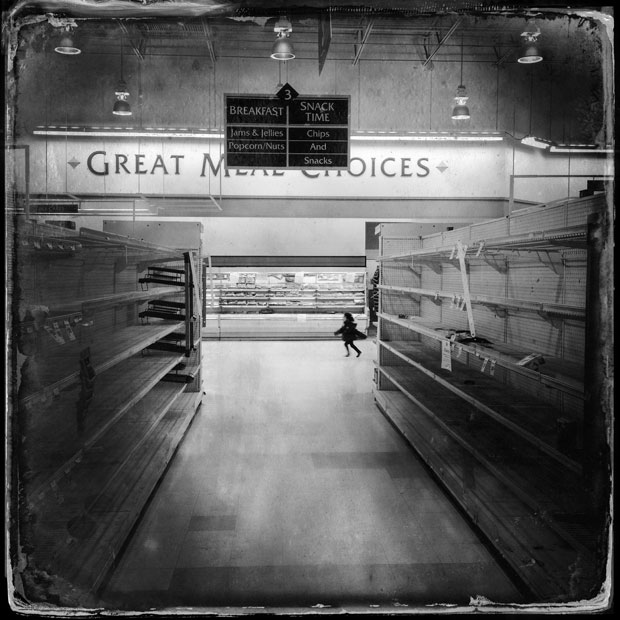

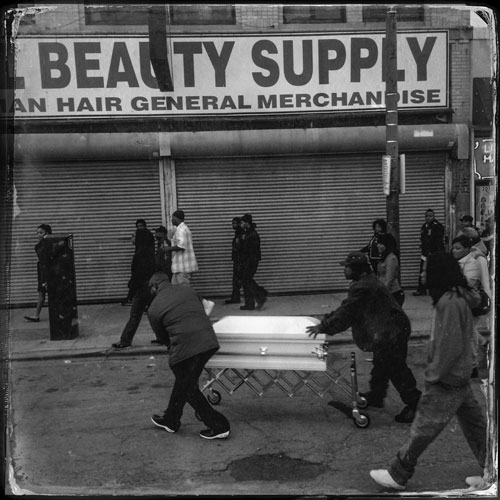

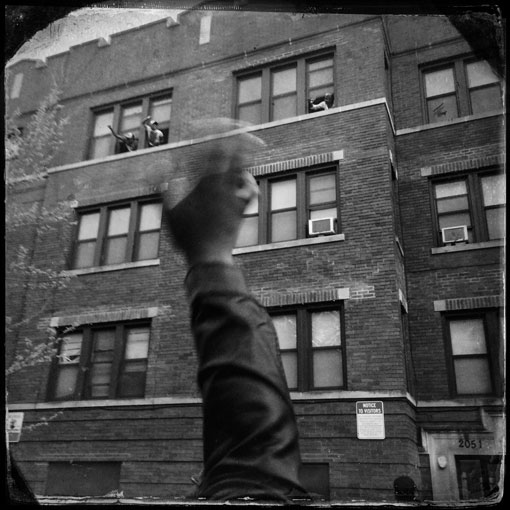

That summer he called on the residents of his South Shore neighborhood to join him for a rally. He borrowed a coffin from a local funeral home and rolled it onto the street to represent the scourge of violence. He wore a dark suit and tie—he felt he always had to project authority and churchly rectitude. To his surprise, 400 people showed up, clogging the intersection. They included guys from opposing gangs, the cliques he’d convinced to gather peacefully. When the police appeared, Jedidiah announced into a bullhorn, “Don’t come to stop us. Join us.” As the group marched through the streets, people leaned out of apartment windows, shouting their support. Jedidiah made sure everyone who wanted to speak was given the bullhorn. “It was a mistake,” he recalled with a laugh. “People said all kinds of crazy shit. But that was my brand—they made up the village.”

•Jedidiah has always held a quixotic belief in the ideal of the village cooperative.•

•Jedidiah has always held a quixotic belief in the ideal of the village cooperative.•

In the following days, he received calls from pastors and politicians and city officials. Now they wanted to work with him. Pat Quinn, then the Illinois governor, requested a meeting, and pretty soon Emanuel was waking Jedidiah up with the occasional morning phone call, asking for updates on his neighborhood. Suddenly, Jedidiah could reach out to city administrators to get a homeless woman into a shelter; after shootings, he was able to contact police commanders on their cell phones, acting as an intermediary between the cops and the guys firing at one another. Glen Brooks, the Chicago Police Department’s director of public engagement, told me that Jedidiah “has definitely reduced tensions at shootings and allowed everyone else to go home safely.”

Invigorated by his success, Jedidiah entered the race for alderman. He was in a local park a couple of weeks later, meeting with at-risk young adults, when an 18-year-old South Sider—I’ll call him Cordell to protect his identity—tried to shoot him. One of Cordell’s friends had just been killed, and he mistook Jedidiah for a rival’s relative. Jedidiah ran for his life. After the incident made the news, Cordell realized he’d targeted the wrong person and wrote Jedidiah on Facebook to apologize.

Cordell had been shot several times himself. He avoided public transportation and the many parts of the city he deemed dangerous, making it hard for him to keep a job. His circumstances had become all too common: Nearly half of the young black men in Chicago are neither in school nor employed, according to a recent study from the University of Illinois. Cordell told me that many young people he knew found a twisted solace in violence. “Negativity is a way to make them feel better about themselves,” he said. “They lost so much, the only thing in their head is they want the other person to feel what they feel.”

Jedidiah was ecstatic to hear from Cordell. He asked the young man to tag along while he worked, and they visited a mourning family together. After that, Cordell started regularly attending a mentoring program Jedidiah helped run. “Jedidiah became that big brother or father figure, inspiring him to be better and do different,” said Cordell’s aunt, who was one of the people who raised him after his mother’s death and father’s incarceration. “He stopped hanging out in the street. He started to say positive things about life. I promise you, without Jed stepping up, my nephew would be dead by now.”

• “Human salvation lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted.” •

I'VE NOW HEARD Jedidiah speak dozens of times, addressing city officials, television cameras, people on the street. Even more than his pastorly locutions, it’s his unmannered rawness that is most striking. Completely immersed in the moment, he braids together bits of Scripture, snatches of recent conversations, current events and his recurring themes of community and fairness—“letting the spirit come out of me,” as he puts it. At his most steely and authoritative, he remains vulnerable, his anger, confusion or awe laid bare. After listening to him address a gathering in Evanston, a political consultant named Bobby Burns volunteered to manage his aldermanic campaign. “It was one of the top three most inspiring speeches I’ve ever heard,” Burns told me. “He speaks so passionately. You can tell that the health of the community he serves directly impacts the health of Jedidiah.”

In the spring of 2015, Jedidiah showed up at a march that was heading to police headquarters. Protesters were demanding the firing of an officer who shot 22-year-old Rekia Boyd in the back of the head while off-duty. Jedidiah was surprised not to recognize any of the young black Chicago activists gathered there. Maybe they were college kids, he thought, with their clothes ripped and covered in buttons. Many wore black hoodies and just about everyone had a hairstyle like an art project. Jedidiah loved what he saw. He had told me, obliquely, that he himself often struggled with his “two realities” and an “inward suffering.” But these protesters, he said admiringly, “felt they could be free and express themselves at a level I never did.”

• JEDIDIAH HAS BEEN PREACHING SINCE HE WAS A TEENAGER. •

• JEDIDIAH HAS BEEN PREACHING SINCE HE WAS A TEENAGER. •

The march was put together by Black Youth Project 100, an activist group very different from Jedidiah’s. It began the week in 2013 that George Zimmerman was exonerated for the killing of Trayvon Martin, as a convening of 100 black millennials, among them students, artists and trained organizers. A University of Chicago political scientist provided guidance, and BYP100 grew to several chapters across the country, with headquarters in Chicago. Charlene Carruthers, the 32-year-old national director, noted that existing organizations in the city, such as the Nation of Islam, were also unapologetically black. “But we’re the only one led by young people, led by women and queer folk,” she told me.

Too often people mistake Black Lives Matter for a social or political monolith, imagining that every young, black protester since Ferguson is a card-carrying member. I once heard a white Chicagoan ask Jedidiah, quite sincerely, if he could instruct all the Black Lives Matter people not to demonstrate in her neighborhood. But the movement is comprised of hundreds of different groups, each with its own motivating principles, distinct politics and methods. A number, like BYP, have proved especially attractive to young LGTBQ people of color, who felt spurned by the conservatism of the black church. They saw the fights against racism, sexism and homophobia as interconnected—“the different kind of struggle you go through daily when you have a marginalized identity within a marginalized community,” DeRay Mckesson said. But other young protesters believed that embracing an LGBTQ agenda diverted attention away from the black men—the Michael Browns, Eric Garners and Freddie Grays—who were being killed by police. “We’re fighting for their liberation,” Carruthers said. “They may not be fighting for ours.”

Although a pastor himself, Jedidiah blamed the city’s black churches for focusing more on their own growth than on embattled young people in their neighborhoods—“being a house of the hireling and not of the shepherd,” he called it, citing the book of John. He had structured Young Leaders Alliance like a church because it was all he knew. He appointed treasurers and secretaries, and he required members to pay dues, like tithing, a sizable $25 a month. “It came to seem antiquated very quickly,” he admitted. “The new protest groups were more palatable to my generation. They had the cool hashtag. They’re rapping and doing poetry and jumping in a circle shouting, ‘We gonna be all right!’” Jedidiah couldn’t help marveling at the way they flouted the politics of respectability and inspired young people who’d been politically disengaged. He saw them as the missing puzzle piece. “That’s not my lane, not my skill set,” he said. “But if I could partner with them—because I also do stuff in the neighborhoods they can’t do—then we can change the city.” And so he introduced himself to a couple of the people at the BYP event.

“We know who you are,” someone cut him off. A few guys who appeared to be functioning as marshals told him he needed to march in the back. Later, Jedidiah recalled, a woman announced loud enough for him to hear that they didn’t need “these coon pastors.” “I was completely rejected,” he said.

Jedidiah tended to work (and sometimes compete) with other maverick South Side activists who seemed to plunge themselves into a never-ending cascade of crises. Lamon Reccord, a reed-thin 18-year-old with his hair cut into a flowering plume, had become a fixture at protests of the police, positioning himself inches from cops in militarized riot gear and glaring flintily into their eyes. But he also headed out alone many nights on what he called safety patrols, hoping his presence would discourage acts of violence. He cleaned up empty lots and washed blood from the sidewalks. “It’s extremely stressful as an activist,” said Aleta Clark, a 28-year-old single mother who sells T-shirts for her anti-violence organization, Hugs No Slugs, and uses the proceeds to feed the homeless and to host events for children. “We don’t get paid, and the world depends on us. Every day something else is going on. There’s so much that’s needed to be done.”

• AT PROTESTS, LAMON RECCORD WOULD POSITION

• AT PROTESTS, LAMON RECCORD WOULD POSITION

HIMSELF INCHES FROM POLICE OFFICERS. •

Once, I was at a community meeting when an angry, tearful mother stood up and accused Jedidiah and the other activists there of ignoring the issue of autism in their neighborhoods. She said cuts to social services had forced her to stay home with her autistic son. No way, I thought, could Jedidiah and his friends take on something like behavioral therapy in addition to everything else they were trying to do. But here they were, faced with this woman’s desperation. A barrel-armed organizer named Artriss Williams, known as Butta, said his uncle worked at a treatment facility an hour west of Chicago. He offered to take the mother there. Vance Henry, a deputy chief of staff to Emanuel, told me he simply couldn’t comprehend the extremes of fearlessness, impracticality and resolve displayed by young black activists like Jedidiah. The best he could do was recite a few wishful words from Martin Luther King Jr.: “Human salvation lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted.”

But Jedidiah felt more maladjusted than most. “This work won’t accept me if I be all of myself,” he said. “That cripples me.” One day, after some impromptu meetings at city hall, we sat down in a crowded Wendy’s in the Loop. A man was going table to table begging for cash, and Jedidiah handed him a $5 bill and asked for three singles back, saying he didn’t have much money himself. He’d spoken to me before about wrestling with his faith in ways that, for him, were uncharacteristically guarded, and I asked him about a fast he said he’d undertaken for what sounded like an improbable 40 days.

Instead of answering, he went silent for a half-minute. When he finally spoke, he said, “You ready? I’m going to give you something that’s difficult. I made a vow to my mother never to embarrass her. The biggest conflict for me—” He paused. “I want to be true to myself, and I’ve not been able to do that becau—” Trailing off, he tried again. “I’ve grown up in conflict with my own self. I couldn’t express my bisexuality. Wait, what’d you ask to make me say that?” A propulsive laugh doubled him over. “I tried to fast like Jesus did in the Bible to eliminate all the same-sex desires,” he went on. “You got an exclusive. I’m giving it to you.” His sexuality, he explained, was a big part of the duality that had always afflicted him. “I’m listening to preachers say I’m an abomination to the God that I love.”

When he was around 16, Jedidiah tried to tell to his mother about his attraction to both women and men. She said he was still her son but couldn’t “shake hands” with behavior that God doesn’t agree with. He had to leave her house, and they had little contact for two years. “I’m still holding on to my faith that God will reverse that mindset,” she told me recently. Jedidiah had long wanted to tell Charlene Carruthers, so she could see that BYP's issues were also his own. But he worried that guys on the streets, along with pastors and many of the activists he worked with, were going to reject him when they found out. “I have to keep quiet while BYP folks yell obscene shit to me,” Jedidiah told me. “It’s a hard place to be in, fighting for people through all that pain.”

There were other ways in which Jedidiah seemed out of step with the uncompromising political moment. In 2015, he endorsed Emanuel’s successful bid for a second term, even though the mayor had closed nearly 50 public schools in black and Latino neighborhoods. Jedidiah said he was swayed by Barack Obama’s support for his former chief of staff. Sticking by the mayor didn’t help Jedidiah’s own campaign—he finished fifth.

Seven months after the mayor's reelection, a judge ordered the city to release the video showing a Chicago police officer shooting 17-year-old Laquan McDonald multiple times at close range. The police had called the 2014 shooting justified, and the 10 officers on the scene, as well as the top police officials who saw the video, kept silent or maintained the false narrative. The video was held from the public for more than a year. Fearing that Chicago would become the next Ferguson or Baltimore, Emanuel tried to meet with young activists before the video’s circulation. Most refused. “Hell no,” Malcolm London, then a leader with BYP100, told me. “You can’t kill us and tell us how to respond.” Many of the protesters were calling for Emanuel’s resignation and the immediate firing of the police chief and the state’s attorney who had failed to bring charges. Some of the activist groups were demanding that public funds be disinvested from the police force and even that the department be abolished altogether.

Jedidiah was one of the handful of young leaders to take the meeting with the mayor. “My approach has always been to exhaust diplomacy,” he said. “I am not anti-police or anti-government. I’m anti-brutality and anti-corruption. I’ve never been of the ‘Fuck the police’ logic.” But he later said that meeting with Emanuel was one of the worst mistakes he ever made. “It was a time to be more abrasive than diplomatic,” Jedidiah said. “Reform wasn’t possible without it.” The board of Young Leaders Alliance removed him as the head of his own organization. “Jedidiah lost his tribe,” said Corey Brooks, the pastor of a large South Side church, who as an outspoken black Republican knew about intertribal divisions. “Most great activists never make it past shouting to create systems and structures. Jedidiah achieved that and had to go back to the shouting.”

On the Friday after Thanksgiving, three days after the release of the McDonald video, Jedidiah joined a protest that shut down Chicago’s “Magnificent Mile” on the busiest shopping day of the year. Days later, the mayor fired the police chief he’d been defending. Other officials who’d reviewed the video resigned. And Emanuel admitted in a speech that a dangerous code of silence existed within the Chicago Police Department.

• JEDIDIAH AT THE THANKSGIVING WEEKEND PROTEST. •

• JEDIDIAH AT THE THANKSGIVING WEEKEND PROTEST. •

The Black Friday rally was a success, showing the power of this new civil rights movement. But it also brought to the surface the internal divisions within the swelling protests. Along Michigan Avenue there were clashes over who could direct the demonstration and who speak into bullhorns and in front of television cameras. Jedidiah marched alongside independent activists he knew. They skirmished with Jesse Jackson, Congressmen Bobby Rush and a cadre of aging civil rights leaders, business leaders and one-time Black Panthers. The young black feminists and queer organizers refused to be marginalized. In a scrum in front of the historic Water Tower, the different factions denounced one another for being too old, too church, too gay, not street enough and too compromised. A woman was punched and a three-way fight broke out. Jedidiah had to recognize that to some of his fellow activists he, too, was the enemy.

• “I thought of the last words I said to him: ‘You need to go back to your momma.’” •

BY THE START of 2016, Jedidiah was living in an apartment several blocks south of his old place, offering free lodging to a half-dozen boarders. He rented a nearby storefront for church services and took a security job at a downtown office building. He still rushed to just about every calamity in the city. At one event, he and Travis stood alongside Emanuel on the steps of a church for the ritual reading of the names of those killed by gun violence. After every victim was announced, Travis shouted, “Oh my God!” “Oh no!” Travis experienced each individual life lost as an unbearable weight. Turning to the mayor, Travis pleaded, “You have to do something about this.”

At 14, Travis was gangly and awkward, less popular with other children than he was endearing to the many adults who ended up looking after him. Jedidiah and Travis’ mother had a contentious relationship. Whenever Jedidiah criticized her, Travis would silence him: “She’s a beautiful person, and I only get one mom.” Travis looked after Jedidiah’s well-being too. They were at Jedidiah's apartment one day when Travis said he knew his secret. “You’re bi and that’s OK,” Travis told him, half-smiling in the way he always did. “You’re so unhappy. You’re trying to please everyone else. Be yourself. Be free.” Jedidiah was shocked that Travis could be so observant. He also felt unconditionally loved.

Still, Travis was a teenager demanding of attention. He often wanted the two of them to go downtown or swimming in the lake, and to his frustration, Jedidiah was usually too busy. “There’s something wrong with my uncle,” Travis would tell other family members. “He won’t talk to me.”

But Jedidiah couldn’t slow down. The violence in Chicago was reaching unprecedented levels—762 murders in 2016, a two-decade high, and an average of 12 shooting victims a day. And then there was the rise of Trump. Jedidiah had seen the clips of Trump supporters shoving black women and sucker-punching black men, urged on by the candidate himself. In March 2016, when a Trump rally was scheduled for Chicago, Jedidiah declared, “Not in my city.” He would go to the event to defend his people.

Once inside the crowded arena, though, he saw the empty stage and an unoccupied lectern, and before he knew it he was leaping over the barricades and scuffling with security guards twice his size. A man wearing an American flag as a cape jumped on his back, and a video of Jedidiah spinning around and landing a right hook became a viral sensation. He didn’t regret his impulsiveness, although he said it led to death threats and the loss of his job. The Bernie Sanders campaign, which had consulted with Jedidiah, distanced itself. But he did wish he’d remembered to shout his message of unity, something like “Power to the village.” Rather, what emerged from his mouth was Hillary Clinton’s lame retort, which he didn’t even believe: “America is already great!”

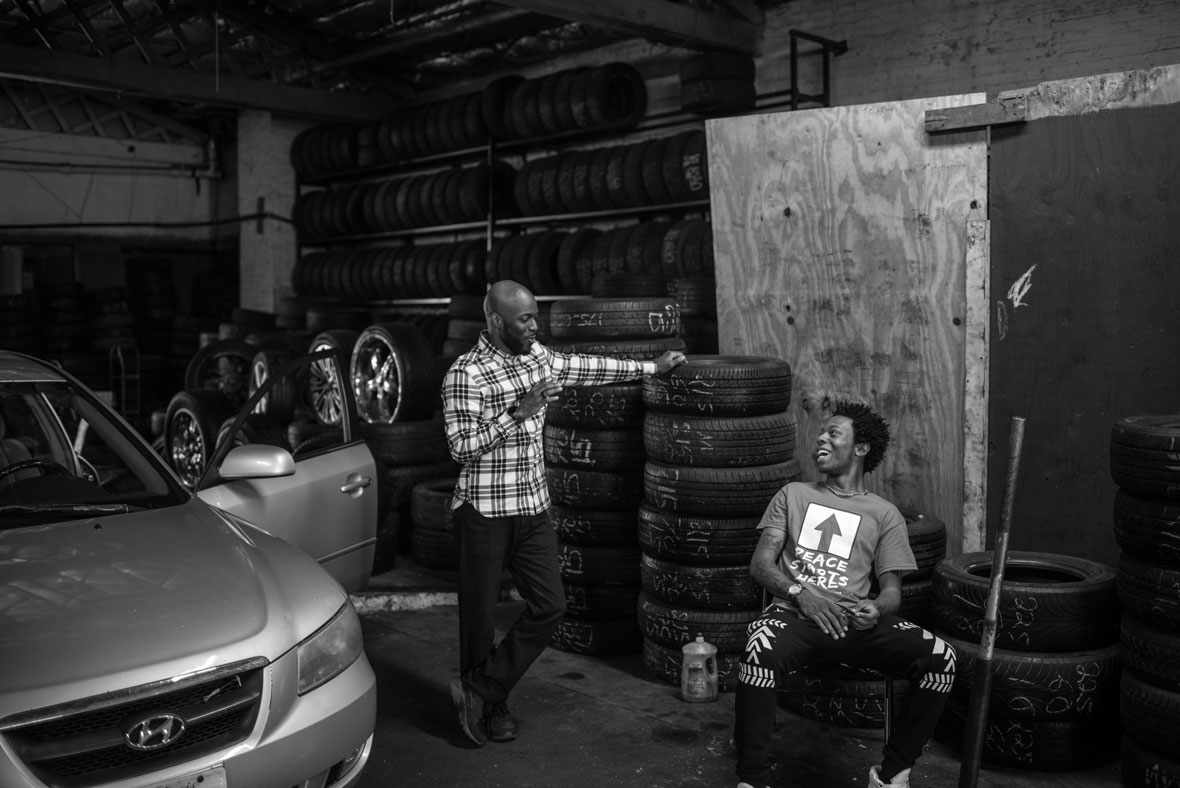

One of his connections in the governor’s office called in a favor, and Jedidiah got a new job as an auxiliary police officer for another security firm, patrolling South Side business districts and public housing complexes. The job suited him. In his uniform, his Glock on his hip, he provided the kind of community policing he believed the city needed. He arrested the people running the drug operations, but he also befriended the young dealers and buyers, addressing the women as “queen” and the grizzled lookouts as “old school.” He shared his cell number freely, and people phoned him in a panic, asking him to break up fights or to calm the mentally agitated.

He was often stationed at the Trumbull Park Homes, a small public housing development in the Wild 100s, the increasingly desolate three-digit streets of the far South Side. One of his partners, a female officer, told me they made quite a team once they figured out that locking up the same residents each day was pointless. Jedidiah regularly bought juice and candy for the many children at Trumbull from a corner deli. “He is very gentleman. Everyone loves him,” the store’s Middle Eastern owner said. “He makes sure no one does the stupid thing.”

• Working at the Trumbull Homes suited Jedidiah. •

And he continued to rush around as if it was also his job to save the city from all its dysfunction. (“Just don’t do it in your uniform,” his boss said of his endless activism.) In August of last year, an 18-year-old was shot in the back and killed while fleeing the police. Jedidiah was afraid of another cover-up. He was working his contacts on the force and in the community, trying to determine what really happened, when Travis asked if they could do something fun together. Jedidiah told him he had no time—there was a big situation in the city he had to address. When Travis persisted, Jedidiah got annoyed. He sent him away for a few days to stay with Travis’ mother in Indiana.

Jedidiah was at the Trumbull Homes that week when he got the call—Travis was in an Indiana hospital and Jedidiah should go there right away. Jedidiah broke 100 miles per hour on the highway. He didn’t even notice the tollway barrier until he crashed through it. Two troopers—both white—pulled him over and one of them trained a gun on him. Jedidiah thought of Sandra Bland. He thought of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, both killed by police only weeks earlier. And yet he couldn’t stop bawling that he had to get to his kid. “It felt like my brain was being torn apart,” he recalled. With the troopers shouting at Jedidiah, a supervisor approached the vehicle. He happened to be black, and he asked Jedidiah for Travis’ name and the name of the hospital, warning Jedidiah that he better not be making up this emergency. Several minutes passed. The supervisor returned. “You need to get to the hospital,” he said.

“And that’s when I knew,” Jedidiah told me, crying at the memory. Travis had gone swimming with a friend and drowned in Lake Michigan. “I thought of the last words I said to him—‘You need to go back to your momma,’” he said. “I was completely not there, trying to deal with that shooting situation. I didn’t apologize and get to say I love him. It kills me.”

• “America broke my heart. Black people broke my spirit.” •

MOUNT GREENWOOD is one of the farthest points of Chicago that cops, firemen and other municipal workers can live while fulfilling their residency requirement. Its main street has an old five-and-dime feel—light poles strung with blue ribbons and bars garlanded with shamrocks. Early last November, a couple hundred residents harried a small band of activists who’d come to protest the police shooting of a 25-year-old black man in the neighborhood. The locals chanted, “Blue Lives Matter” and “Trump.” They circled the protesters, threatening to lynch them. So on the night of the presidential election, three months after Travis’ death, Jedidiah implored people to meet him in Mount Greenwood after voting. “We will get the election updates on the very grounds where white supremacy obviously thinks it’s safe to thrive in Chicago!” he announced on Facebook.

Word of his impending arrival spread through Mount Greenwood, with calls to defend the neighborhood from “the terrorist/hate group Black Lives Matter.” Jedidiah was met by raised middle fingers and jubilant howls from several hundred people massed on the streets. Someone swung a flagpole. Jedidiah said an older woman called him a “dumb nigger,” and the cop separating them broke rank and said, “Mom, you’re embarrassing me.” Amid the tumult, Jedidiah took a bullhorn from a fellow activist. “If black lives matter and blue lives matter,” he bellowed, “then what are we fighting for?”

Forced to flee, Jedidiah endured the additional blow of the election results in his apartment. “The people who talked about lynching—that thinking, that ideology—they won,” he said in disbelief. And yet it was because of the loss that he returned to Mount Greenwood the following week. He met with local clergy, politicians and business leaders, along with officials from the police department and the mayor’s office. “There are a lot of black and white people who are ignorant and ill-informed,” he told the group. “But we can get out the message that we’re not all bad and we’re listening to one another.” For six hours over two consecutive days, Jedidiah did listen and explain and demand. “A black assertion of our quality of life does not equate to an attack on white people,” he said. It was a commanding performance, halted only when he bowed his head mid-sentence and large tears began to hit the table in front of him one after another.

One person came with Jedidiah for the meeting the first day—me. He’d invited other activists, but they all said they wouldn’t negotiate with white racists and oppressors. They told Jedidiah he was naïve. Ja’Mal Green, a 21-year-old whom Jedidiah had once considered a protégé, dismissed him on social media as a puppet with a slave mentality. Jedidiah believed he was doing the harder thing, trying to bring the segregated city together. Yet the pain of being forsaken—by the very people he felt he served—it buckled him. “America broke my heart,” he said of Trump’s election. “Black people broke my spirit.”

• THE CONSERVATISM OF JEDIDIAH'S CHURCH HAD WEIGHED

• THE CONSERVATISM OF JEDIDIAH'S CHURCH HAD WEIGHED

HEAVILY ON HIM FOR YEARS. •

Mount Greenwood broke him in other ways as well. Two of his colleagues at the security firm told me that Chicago cops started harassing them because of their affiliation with Jedidiah, pulling them over, blinding them with flashlights and claiming to be looking for “Mr. Brown.” The firm’s owner showed me posts from the community blog for the Mount Greenwood ward that shared his personal details—his address, his children’s schools, the fields where he coached T-ball. Jedidiah decided he had to resign to avoid endangering anyone. Without a job, he eventually received a five-day eviction notice. His fridge went empty. He stowed his car to avoid the repo man. But he didn’t feel he could tell anyone. He believed that word of his financial troubles would affirm racist stereotypes and longtime assaults on his character. It was then that he stepped down as the pastor of his church and quit activism too. “Chicago has taken too much,” he said. “I don’t have another 10 years to give.”

Other activists were energized by Trump’s election—the structures of racism and inequality they’d long decried were at least out in the open for all to see. “Now is the prime opportunity that radical transformation demands,” Charlene Carruthers told me. But for Jedidiah, his vision of the unifying village had come to seem preposterous.

In relinquishing his responsibilities, Jedidiah did find a certain liberation. The conservatism of his church had weighed heavily on him for years, the contradictions between his own complicated personal life and the congregation’s beliefs forcing him to become a distorted version of himself. He wanted me to write about his sexuality now, he explained, to honor Travis’ candor with him. “I’m not going back to that level of intense dishonesty that contributes to this unhappiness,” he said. He started dressing more casually, in a kind of SWAT chic—black “Chicago” baseball cap turned backward, black work boots and a black sweatshirt tucked into black jeans. He got his first tattoo—Travis’ name across his chest. One Monday he told me that he’d been at clubs over the weekend with a girlfriend, staying out until 5 a.m. A man dancing beside him said, “You’re the guy from the news, the activist. Aren’t you a pastor?” Jedidiah said not anymore. “Can I get your number then?” the man asked. When Jedidiah told me the story, his legs jellied with laughter.

• Jedidiah celebrated his 31st birthday with a newfound sense of freedom. •

• Jedidiah celebrated his 31st birthday with a newfound sense of freedom. •

But although he kept repeating that he was retired from activism, he couldn’t stop himself from responding when he learned of people suffering. On the morning in January that the Department of Justice delivered its damning investigation of the Chicago police, finding that the CPD had routinely and systematically used excessive force against minorities, I went with Jedidiah to the home of a 21-year-old murder victim. We were accompanied by Cordell, the 18-year-old who had tried to shoot Jedidiah a few years earlier, and also Martin Johnson. Known as the “Crime Chaser,” Martin listened to police scanners at all hours and raced off to stream video of the crime scenes—to force the police to do their jobs, he explained. He’d filmed the aftermath of Shadara Muhammad’s homicide earlier that week. She’d been struck by a car, her lifeless body left in the bushes like roadkill. As we drove to the public housing development where she’d lived with her family, Jedidiah said he couldn’t bear that this young woman’s death had gone largely unremarked and uninvestigated, as if her black life truly did not matter. “I’m still a resident of Chicago,” he said.

The Muhammads’ two-story rowhouse was spare and neat, 10 paces between the front and back doors. Graduation photos hung on the wall, and a couple of young children peered down from the stairs leading to the second floor. Their mother sat in pajamas on a sofa, curled into herself. Her oldest son warned her to stop crying or she might have to be strapped down again. An aunt, a neighbor and a niece started to explain in a rush that they hadn’t been allowed to see Shadara’s body, that a detective hadn’t even introduced herself. The mother began to wail, and Jedidiah realized that he had to take control of the room. It was a magical thing to witness.

“It’s OK to be angry with God,” he said, cradling Shadara’s mother in his arms.

“OK,” she whimpered.

“I lost my 14-year-old son, and I was very angry with God.” The cramped box of the living room fell silent. “I’m going to pray, and we’re going to figure out what’s going on,” he went on, his voice an enthralling crescendo. “Father God, I’m asking you to give this mother comfort in her moment of grief. Stabilize her thoughts and heart. Cause the memory of her child to be what leads her in fighting for the justice she deserves.” After the chorus of “amens,” he asked what kind of person Shadara was, and the mood brightened, the family calling out her traits—a manager at True Religion jeans, a dancer, petite like her mom, funny. Jedidiah asked permission to act as their spokesperson. “I am going to stand with you all,” he assured them. “We are family as of today.”

There was some confusion about conflicting vigils and competing GoFundMe pages. An older sister was waiting on the T-shirts with Shadara’s face printed on them, and she and her brother debated the tattoos they were getting in her honor. In neighborhoods racked by death, these were among the evolving conventions. The Crime Chaser, who stood with his bleating police scanners in a rolling case by his side, pointed to Jedidiah as a way to conclude the meeting. “Remember that guy who ran onto the Trump stage and had to be dragged off?” he asked. “That was him.” The room erupted with cries of delight. “I like that in you, brother,” the aunt said, and she hugged Jedidiah and then pulled him in to embrace him a second and a third time.

Minutes later, Jedidiah was phoning a police contact to get the name of the detective overseeing Shadara’s case. I was standing beside him when he reached the detective and asked if they could meet. “No,” she said flatly. Just that morning, Emanuel had agreed that the police urgently needed to gain back the trust of black communities. The CPD closes between 20 and 30 percent of its murder cases, a historic low. How many wasted opportunities were there like this one to change the public’s perception of the cops? “You are telling me you will not work with me and I can possibly help you on this case?” Jedidiah asked. “Do you want to wait until after the press conference to talk to me?” That got the detective to agree. Jedidiah also arranged for the media to attend the vigils. Stories about Shadara appeared in the news, along with a hotline for anyone to call with information. The police checked cameras around the crime scene and announced that they were looking for the driver of a white Mercedes SUV. The car was located the next day.

The effort, Jedidiah explained, was draining. “Could you imagine doing that every day?” he asked me. But he admitted he felt as good as he had in months. “I’m going to treat those kids to a meal, and know that auntie and that attitude they got,” he said of the Muhammads. “I didn’t know them before this tragedy. There aren’t even words for it. I feel an unbelievable sense of joy. It’s a gift.”

• “In my religion, hell is the place you go for suicide.” •

A few days later, he embarked upon an ambitious new campaign. He said it came to him like a vision while on a pilgrimage to Atlanta for Martin Luther King Day. He would lead a march through all 77 of Chicago’s communities, convening block meetings and assemblies along the way. By collecting donations, he’d be able to create opportunities in areas brought low by crime and hopelessness. “I’m getting excited about Chicago again,” he told me. “I’m going to get louder.”

On the Monday when Jedidiah started his walk, the temperature was in the teens, the wind spirit-crushingly cold. That day, he covered three blocks on the distant South Side. No one answered at most of the homes. But a retired African-American cop gave him a dollar. And a woman cracked her door just wide enough to slip him a $5 bill. A man who’d lived in the neighborhood for 26 years said his children had abandoned Chicago; his son wanted him to relocate as well. “You can’t run away from your problems,” he said. “You have to face them. I just need a leader to work with.” For an hour, Jedidiah was joined by Lamon Reccord, who, at 18, had already worked on numerous political campaigns. He gave Jedidiah tips on how to hone his pitch, his energy intoxicating. Jedidiah treated each donation as a minor miracle. “I am so humbled and hope filled!” he tweeted when someone gave $100.

But he still had no job, and an eviction was looming. There was a night when he dashed to a corner near his apartment after seven people, including a 12-year-old boy, were shot at a memorial for a slain friend. Then Jedidiah learned that a 15-year-old had been murdered. And after that a 19-year-old activist he knew died in a car crash. Then in separate incidents on the same evening, an 11-year-old girl and a 12-year-old girl were both shot in the head; each would eventually die of her wounds. Jedidiah didn’t know the families, but he blamed himself nonetheless. If someone could do that to children in his city, then he had failed to change enough hearts.

•“I see lives being destroyed, and I don’t know what to do,” Jedidiah once said.•

On a Sunday morning in February, he showed up at the hospital where the 11-year-old, Takiya Holmes, was still on life support. He was hoping to pray with those holding vigil or at least buy them a meal. One of Takiya’s cousins, a 26-year-old named Rachel Williams, was then an organizer with BYP100. Rachel had often called the girl her baby, and encouraged Takiya to become an “activist nerd” like herself. Just as Jedidiah did, Rachel worked with families in the city who’d lost loved ones. But now it was her own little cousin tottering near death, and it was Takiya’s three-year-old brother who’d be haunted by seeing his sister “breathing blood.” “This one feels like daggers stabbing me, and it doesn’t go away,” Rachel told me. She, too, would soon scale back her activism. At the hospital that day, Rachel saw Jedidiah only as an interloper parading for the news cameras. “This is not the family you want to do this with,” she said, as they began to argue. She yelled at him to get out.

Jedidiah reeled from the hospital to his family’s post-church meal. He was weeping as he entered the restaurant. “I don’t know why these people hate me so much,” he told the table. “I just wanted to help.” He failed Takiya Holmes and her family, he said. And he failed Travis, who was never far from his thoughts. Jedidiah said he shouldn’t have taught Travis to be fearless. Then maybe he would not have braved the waters that were too rough for him. That’s when Jedidiah’s younger sister, trying to console him in a way, corrected him. Travis hadn’t drowned accidentally. It was a suicide. Travis, who could seemingly tell Jedidiah anything, didn’t share with him the other side of what he felt. Or maybe he had tried to speak of his fears that he was a burden, the cause of his family’s dysfunction, and Jedidiah just hadn’t noticed.

“I can’t live with this thought I indirectly killed the greatest human ever trying to do for this ungrateful-ass grave called Chicago,” Jedidiah texted me not long after he left the restaurant. When his child needed him most, he had charged off to help some people he’d never even met. “In my religion, hell is the place you go for suicide,” Jedidiah told me later. “If that kid is eternally damned because of me, I deserve to be there too.” So he grabbed his gun and veered off Lake Shore Drive near the Loop.

“I can never recover from this,” he cried on Facebook Live that afternoon, his finger tensing against the Glock’s trigger. “I wasn’t there for him because I was trying to be there for you all.”

• And then Jedidiah learned that he wasn’t alone. •

THAT NIGHT, the police confiscated his gun and took him to the hospital. Jedidiah told a psychiatrist he hadn’t pulled the trigger because he thought God might be sending him a sign. When it looked like he’d be committed to a mental institution, he kicked open a door and bolted.

I showed up at his apartment the next day, along with dozens of people who were overjoyed that he was alive yet fearful for his state of mind. Jedidiah cried for stretches, overcome with shame and despair. His mother perched on a chair in a corner. His father positioned himself silently beside his son. The police superintendent called to check on Jedidiah. So did an aide to the mayor, a congressman and the mother of Sandra Bland.

Jedidiah joked to his visitors that he fled the hospital because black people don’t believe in therapy. But then an activist friend sitting at the kitchen table offered cautiously that he’d spent time in a mental hospital. He said he wasn’t sure he’d be alive without it. Several other organizers shared that they had battled depression after everything they’d experienced in the streets. Their desperate efforts to rescue everyone meant they were tortured by the inevitable failures. Lamon said 15 of his friends had been killed in Chicago over the last couple of years and he’d gone into a dark place too many times to count. Others told Jedidiah they had thought about dying and, in some cases, had tried to kill themselves—they’d just had the sense not to put it on blast on Facebook Live.

But there was an unexpected upside to Jedidiah’s livestream: He learned he wasn’t alone. In the afternoon, 10 activists showed up and sat in a half-moon around him, with one, William Calloway, leading what seemed like an intervention. Jedidiah had clashed with several of them, disagreeing over technique or just elbowing for room in the same fervent, exhausting space. They told Jedidiah stories of their own torment. The work they did in Chicago at times consumed them like a fire, and they’d each taken breaks to cool their overheated minds—if not also to stay solvent or patch up their personal lives. Some had quit activism altogether to preserve their sanity. William insisted that Jedidiah step away to heal.

• JEDIDIAH AND LAMON RECCORD •

• JEDIDIAH AND LAMON RECCORD •

“A lot of these people fought me,” Jedidiah told me. “Now we communicate on common ground.” He soon left for California, where one of his sisters lived. He met with a therapist, who told him that what he suffered from was caring too much. That was a diagnosis he could embrace. I saw Jedidiah regularly in Chicago over the following months. At 31, he was rebooting, he said. He wouldn’t give up on the city that hadn’t given up on him. Sure, some people still laid into him on social media, saying his suicide attempt was a publicity stunt. In September, he led weeks of protests outside a suburban hotel, after speculation swirled around the death there of a 19-year-old African American woman found in a walk-in freezer. His reemergence brought a new round of attacks on his motives and character. But most places he went, people stopped him, saying, “You’re the activist Jedidiah Brown!” They mentioned something he’d done that they admired or that had given them direction. Teenagers called him a role model. A gang chief thanked him for treating his guys with respect.

Recently, Jedidiah decided to take on Rahm Emanuel and run for mayor in 2019. It would be the people’s campaign, he said, a way to highlight the plight of black neighborhoods and demand the same quality of life as in other parts of the city. The T-shirts he had made declared, “I’m running for mayor with Jedidiah Brown.” His car had finally been repossessed, so now he took the bus or Uber to spread his message. He still believed he could convince the people of Chicago that they, too, needed to care too much.