In the solitary unit at High Desert State Prison in Nevada, the guards usually follow a simple practice: Never let two inmates out of their cells at once, because you never know what might go wrong. The prison is a massive complex less than an hour from Las Vegas, surrounded by electric fences with razor ribbon and then miles of brush and gravel. In “the hole,” as the solitary unit is known, inmates are isolated for around 23 hours a day—sometimes because they’re being punished, sometimes for their own protection. One evening last November, a 38-year-old corrections officer named Jeff Castro was supervising prisoners as they took turns in the shower cage when two inmates were released into the corridor at the same time.

Andrew Arevalo was a heavily tattooed, round-faced 24-year-old who had been convicted of stealing two paint machines. Carlos Perez, who was four years older, was serving time for hitting a man with a two-by-four and was due to get out of prison in March. Even though they both had their hands restrained behind their backs, they started trying to fight. To Steve McNeill, a prisoner who was watching from his cell, it looked pretty funny: two guys in T-shirts and boxer shorts yelling at each other, clumsily kicking at each other's shins and then backing away. “Neither could affect an effective offensive,” McNeill recalled. “It was like some awkward and quirky dance, then 'BOOM.'”

About 30 feet away, another officer was manning the control room—a trainee named John-Raynaldo Ramos. His job was to remotely open the cell doors from “the bubble,” the glass room overlooking the floor. The elevated booth is equipped with a 12-gauge shotgun loaded with 7 1/2-birdshot—the same tiny pellets that sport shooters use to blow apart clay pigeons and that hunters use to kill birds and rabbits. The windows of the bubble, which are reinforced with security bars, can be opened to aim a gun through. “Get on the ground,” Ramos ordered the two men.

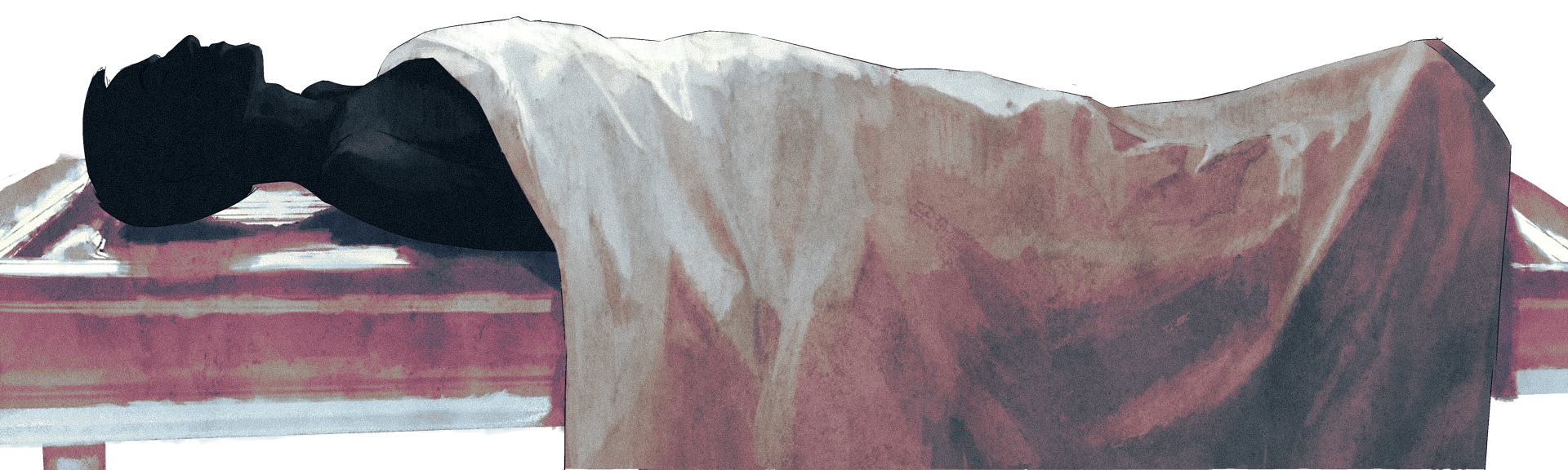

Ramos fired a warning shot, but the prisoners kept scuffling. Then he fired three live rounds. When he stopped, the left side of Arevalo's body was loaded with shots. Perez lay motionless and bleeding on the floor, near a shower bag and a towel. He had at least 30 pellets in his face, 30 in his neck and as many as 200 in his chest and arms. Ramos asked another officer, Isaiah Smith, to call the prison medical staff while he tried to reload his gun.

About an hour after being released from his cell, Perez was pronounced dead. Arevalo was taken to the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada in Las Vegas, where staff recorded that he had retained “extensive” shots to the “left face, left neck, left arm, left chest, left flank.”

Later that night, Ramos admitted that he had fired on the two inmates. “They continued kicking each other even though they were bleeding,” he explained in a report. (This account of the shooting was drawn from Ramos’ report, legal complaints filed on behalf of Arevalo and Perez’s family, including witness descriptions provided by their attorneys, and the coroner’s report. Smith’s lawyer declined to comment, Castro did not respond to multiple interview requests, and Ramos could not be located. None of the officers have responded to the lawsuits.)

But Ramos also claimed in his report that it was Arevalo who had killed Perez. At a disciplinary hearing in January, Arevalo was found to have committed battery, assault and murder. He was stripped of his personal property and punished with 18 months of solitary confinement. As far as the prison was concerned, nobody else bore any responsibility for Carlos’ death.

McNeill continued to have nightmares about the incident. More than a year later, he woke his cellmate up in the middle of the night with his screams. “I keep seeing the scene from Carlos’ point of view and waking up in cold sweats,” he recounted. “I run from the fight, and they shoot me anyway. I lie down, and they shoot me anyway.” In a recent letter, he wrote, “You just want to go to a safe place, but there isn't one.”

“Shot in face, neck, and chest, went down and was shot two more times, helicoptered to hospital, 3 surgeries, hospitalized ... severe loss of vision (pellet lodged under eye), paralyzed mouth,” Reginald McDonald, an inmate in the Lovelock Correctional Center in Nevada, wrote to a prison advocacy group of a shooting that took place in September 2011. "There's still over 100 lead pellets in my body, please respond.” His injuries were later documented in medical records filed in court; another inmate wrote to the organization that he had seen McDonald “laying in his own blood, bleeding profusely from his face.”

There is a lot of shooting going on inside Nevada’s correctional system. This year, at least 22 inmates at three facilities were injured by shotgun blasts. In the first half of 2015, shotguns were used in 14 incidents at High Desert alone. Three were birdshot, the rest blanks. Throughout the state, on average, officers fired a live shotgun round once every 10 days between January 1, 2012, and June 26, 2015, not including warning shots, according to the Nevada Department of Corrections (NDOC). Correctional institutions are notoriously secretive about their security policies, but this much can be said: It isn’t normal for a guard to fire a gun inside a prison.

In policing, guns are carried by most rank-and-file officers. But the correctional system places far tighter restrictions on the use of firearms. Officers might carry guns while patrolling the perimeter or transporting inmates, and prisons also store weapons in secure armories in case of riots or hostage situations. But on the inside, if guards need to suppress a fight, they typically use tasers, gas, physical force, or simply try to calm the inmates down. Multiple corrections experts confirmed that it is rare for a guard inside a prison have access to a gun, let alone shoot one. The Federal Bureau of Prisons, which houses the Unabomber, the shoe bomber and a Boston Marathon bomber among its nearly 200,000 inmates, has “always operated under the principle that firearms are not routinely carried within the institution,” a spokesperson said. Only 15 states out of 50 responded to requests to provide details on their prison firearms policies. None of them—including the large prison systems of Texas and Ohio—reported using guns for everyday inmate management. There are many alternative tools that pose fewer risks to both prisoners and guards, says Steve Martin, who has served as an expert witness in court cases involving the use of force by corrections officers. And if an inmate were to somehow get hold of a gun, Martin adds, it would be “about [the] worst-case scenario a prison manager could face.”

They do things differently in Nevada. The state has the lowest ratio of guards to prisoners of any correctional system in the country—only about one security staffer for every 12 inmates, according to the Association of State Correctional Administrators. For this reason, the state “relies heavily” on the use of shotguns to keep the peace inside its facilities, ASCA found in a 2015 study requested by the NDOC after Perez’s death. (The NDOC disputed this assessment, claiming that its staff ratio is one guard for every five inmates and birdshot is not the “primary means” of control.) “[S]everal seasoned officers ... are concerned for the Department and the safety of all who are under our charge,” James Kelly, the secretary for the Nevada Corrections Association, wrote in May, making reference to “recent events” at High Desert.

At the prison, guards like Castro and Smith didn’t normally carry chemical spray, batons, handcuffs or whistles at the time that Perez was shot. But in at least six of the state’s seven correctional facilities, including High Desert, officers can access shotguns loaded with birdshot in designated posts elevated above housing units, the dining hall or outside areas. Certain posts also contain Ruger Mini-14s, which are lethal semi-automatic rifles. Under department policy, officers are allowed to pull a gun to get inmates to behave, and this is not considered physical force. They must give multiple verbal warnings and fire a warning shot in the air before they can shoot a live round. But if there’s a fight that could cause serious injury—an inmate doesn’t necessarily have to have a weapon—officers are allowed to skip birdshot off the ground, on the logic that a violent prisoner might stop hurting someone if he’s hit in the legs.

The state defines this method as a “non-deadly” use of force, but a shotgun loaded with pellets can easily draw blood from as far as 50 yards away. And when guards skip birdshot off the floor, the pellets “can be very unpredictable in their trajectory,” the ASCA found. Before officers start shooting, they may order prisoners to hit the ground—even though the shots travel parallel to the floor. “You're shooting directly at them,” says Sabree Lyons, who said he witnessed multiple shootings during the two-plus decades he spent as a prisoner in the Nevada system. “What do you expect these inmates to do?” says Lyons, who now works part-time for a law firm that represents inmates in shooting cases. “Get up and run away from the situation? Now you’re going to shoot them because they're running away.”

In addition to the Perez shooting, at least three inmates have recently sued the Nevada Department of Corrections after being wounded by birdshot pellets at High Desert. On July 31, 2012, Dario Olivas, then 21, was eating a brownie in chow when prisoners got in a fight less than 50 feet away. In his complaint, he said he was hit in the face and upper body by ricocheting pellets and blinded in his right eye. Officers, he told me, consider bystanders “like a casualty in war, you know?” (Afterwards, he added, the guard who shot him apologized.) Olivas has since been released. His depth perception is off, his family doesn’t trust him to drive and he’s trying to obtain disability payments. A federal judge dismissed his lawsuit against the NDOC in September, partly on the reasoning that an accident is not considered a form of cruel and unusual punishment.

Two days after Olivas was shot, Ryan Layman, an inmate with a history of mental health problems, threw his tray and cup across the cafeteria. Layman claims in his lawsuit that a guard shot him in the hand. (A judge dismissed the case in September 2015.) And a 62-year-old inmate named Lawrence Evans alleges that in January 2012, an officer skipped more than 400 pellets of birdshot off the ground to break up a dining hall fight. Two officers and 11 inmates were hurt, including Evans. “It felt like my entire left side was shredded!” Evans wrote later. Afterwards, officers needed two blood spill kits and a mop to clean up the scene of the fight.

The officer who fired the gun testified that he “did not shoot ... to be mean or cruel, but only to restore order to the dining hall.” Nevada's lawyers, meanwhile, argued that guards had followed policy appropriately and that collateral damage was “unfortunately” a possibility with birdshot. Two years later, a radiology report noted that Evans still had “numerous” bullet fragments embedded in his body. Evans mailed his attorney a bag last year containing more than two-dozen pellets he’d dug out of his skin with help from his cellmate. “There's still plenty more,” he wrote.

To understand how Nevada came to be this way, why its prisons are such an outlier in the American correctional system, you have to start with a man named George Sumner.

George Sumner was the product of a very particular time and place: the California prison system during a notoriously bloody time in its history. Born in Oklahoma in 1932, Sumner was an imposing presence—6-foot-3 and more than 200 pounds, with an incongruously soft voice. His size made people think he was a “Neanderthal, [but] he was a bright, complicated guy,” says Jeffrey Schwartz, a correctional consultant who once ran a hostage training program with him. In December 1976, Sumner became warden of California’s oldest prison, San Quentin, just as the state embarked on tough criminal justice policies that would increase its prison population by 572 percent over the next three decades.

When Sumner took over San Quentin, gangs like the Black Guerilla Family and the Aryan Brotherhood had made it “a bad place to pull down hard time,” as an inmate once put it. That decade, 12 correctional officers were stabbed, shot, thrown off tiers or bludgeoned to death in California—almost half of them at San Quentin. In June 1979, two former staffers told me, a couple of Aryan Brotherhood members butchered another inmate so thoroughly that the cell was smeared with blood. Anthony Newland, a senior staffer under Sumner, said that bodies of inmates who had been murdered overnight were occasionally put on his desk because the coroner only worked during business hours. “I had the longest desk,” he recalls. (“Deceased inmates at San Quentin State Prison in the 1970s were never placed anywhere except the morgue,” a spokesperson for the department said.)

Sumner’s mission was to halt the bloodshed, and guns were to be a significant part of his strategy. Because California prisons historically had a low proportion of guards to inmates, they had built gunrails, or catwalks where officers could stand with firearms. Each of the state’s 12 prisons improvised their own weapons policies. Two staff members who worked with Sumner during this period recalled that he was an early advocate of using birdshot to shut down fights and riots. “We didn't have a lot of sophisticated, more modern techniques,” says Robert Ayers, who worked at San Quentin from 1968 to 1987 and went on to serve as the warden at four California prisons. “Birdshot was deemed the best available alternative.”

It wasn’t exactly a great success. Some inmates regarded the pellets lodged under their skin as a badge of honor. Others packed books, newspapers and magazines underneath their clothes like makeshift flak jackets to protect themselves. “It really upset the librarian, the books got all shot up,” says Newland. Plus, some staffers worried about the birdshot bouncing off the ground and hitting people in the face. “We just determined it was not a good control mechanism,” says Ayers. In the mid-1980s, San Quentin stopped using birdshot and started giving guards even more powerful Mini-14 rifles.

But by that time, Sumner had moved on. He left San Quentin in 1981, at a time when the culture of prisons was starting to change. For decades, wardens had been autocrats lording over their own miniature kingdoms. Now, things were becoming more standardized, more bureaucratic. And Sumner, who was once sucker-punched by an inmate at San Quentin and punched him right back, was no bureaucrat. “George was a patriarch,” says Newland. “He could deal with all the changes as long as he remained the patriarch.” Luckily for Sumner, he had managed to find a place that welcomed his approach: the Nevada State Prison, a troubled high-security facility near Carson City.

Not long before Sumner arrived, two prisoners armed with homemade knives had taken 10 people hostage, including a prison chaplain, and (unsuccessfully) demanded a helicopter. It was the fourth hostage incident at the prison in only five months. Staff from that era talk about a particularly hazardous area known as the “gauntlet”—a space less than 20 feet wide between two housing units on a hill. Inmates would hide at the bottom of the hill, where they couldn't be seen from the top, and hurl rocks at the guards, says Bob Bayer, a former director of the Nevada prison system. In November 1981, Sumner told the state legislature he wanted to build a $179,000 gun rail to overlook the gauntlet. From his previous experience in California, he explained, “gunrails have saved lives.” Under Sumner’s direction, officers started using birdshot, said Bayer and another former NDOC director, Jackie Crawford. By the mid-1980s, when Sumner became director of the entire Nevada Department of Corrections, the policy was widespread, according to ASCA.

It also survived numerous legal challenges. In 1994, a Nevada inmate sued a trainee officer who fired near him with birdshot. But the 9th Circuit found that the policy didn’t constitute an excessive use of force, because it had been used in a “good faith effort to defuse a volatile situation.” Sumner died the same year, from cancer. (His family declined to comment for this story.) But his firearms policy has persisted in Nevada to this day, despite a marked shift towards rehabilitation in prisons and the development of entire new technologies and methods for dealing with inmate violence.

California, for instance, has long since stopped relying on guns to manage prisoners. By the late 1990s, after adopting more powerful weapons, the state was paying out massive settlements to shooting victims. The state tasked a former assistant director of the prison system, Richard Ehle, to review some of these incidents. Ehle oversaw a panel that examined as many as 100 cases, and found that many violated state and federal law. In 1998, the California Department of Corrections sent a note to staff members declaring that “deadly force is not intended to stop fist fights.” The next year, the department overhauled its use of force procedures and retrained at least 46,000 staff members in new methods. Between 1993 and 1995, 17 inmates were fatally shot in the California prison system. Between 1999 and 2002, when the new procedures were in place, that number dropped to one. There are still armed posts in the state’s prisons, but lethal force is no longer used to break up fights, a spokesperson said.

Nevada, though, remained stuck in a time warp. Newland recalled that in San Quentin, doctors often used to leave birdshot in inmates’ skin until it worked its way out—”like your mother might do if you got a splinter,” he explained. “My mother would always say, 'Just leave it, it'll fester, it'll come out on its own.'” I told him that this still happens in Nevada, and Newland started laughing. “Oh my God,” he says. (NDOC responded that it treats inmates “case by case based on their medical needs.”)

Bayer, the former Nevada prison system director, helped design the High Desert facility in the mid-1990s. He maintained that the birdshot policy has persisted because it is effective, explaining that NDOC has to “do more with less.” But he also insisted that administrators are committed to the safety of both guards and prisoners. “The first word out of my mouth when I answered a late-night call—and there were many—was to ask if any staff or inmates were hurt,” he says. “In short, we really do care.” Jackie Crawford, who served as Nevada's director of corrections from 2000 to 2005, also pointed to the state’s historically low staffing levels. She described an instance when inmates were fighting under a gun post at High Desert, but the officer was too close to fire on them. One inmate was seriously injured and subsequently died, she said. However, she added, “You can’t control inmates just with gun towers or other uses of force. There needs to be treatment, training, education and meaningful work programs.” The warden of High Desert when Perez was shot, Dwight Neven, defended the policy emphatically in court in June 2015, testifying that it protects officers. The law, he said, allows “my officers to break up even a small altercation in the dining hall with whatever level of force is necessary.”

Ehle told me that Nevada officials need to examine whether the use of guns is justified. “If they say, ‘in most instances, yes,’ then OK. What we found in California, through the lawsuits and our experience, is that firing at two inmates in a fistfight in the yard, and shooting them dead because they wouldn’t comply … just did not pass muster.” He added, “If you’re deploying it and you're saying it’s not lethal, but it has lethal potential, I think you’re deluding yourself.”

Victor Perez was doing an overnight run in the semi-truck he drove for a shipping company when his wife called to tell him that his little brother Carlos was dead. The two had been close in childhood, although as adults their lives had taken very different paths. Victor, who is 30, got married, had kids and settled down in Reno. Carlos got addicted to heroin and went to prison. Victor had taken in Carlos’ three children—a toddler girl and twin baby boys, although one of the boys, Carlos III, died at the age of 2. Victor planned to find Carlos a job as a forklift driver at the shipping company when Carlos got out in a few months’ time. After that, the family hoped Carlos would eventually graduate to being a full-time father again.

The morning after he received word of Carlos’ death, Victor called the prison to find out what had happened. All anyone would tell him was that there had been an “incident.” So Victor drove out to High Desert, along with his wife, mother and another brother. They spent about 45 minutes talking with Neven and other staff, who said Carlos had died after a confrontation with another inmate but refused to give more details. The warden’s manner was cold, Victor recalls: “It was just, 'He's dead, and there's nothing else we can do. There will be a report.'”

A few days later, the family went to the funeral home and asked to see Carlos. The counselor there expressed concern about the state of his body, since Carlos had been shot. “What are you talking about?” Victor demanded.

At this point in our conversation, Victor was sobbing so hard that he could barely speak. He told me that when the family went in for the viewing a few days later, Carlos had been laid out on a table. They unbuttoned the blue plaid shirt they’d provided to the mortuary and pushed back his long black hair. Two white bandages crisscrossed his tattooed chest where the coroner had sliced him open during the autopsy to remove his organs. He had bruises on his hands, which the family believes were caused by the handcuffs. And his face, head, neck, chest and stomach were punctured with hundreds of small open wounds. Carlos’ mother had to leave the room, Victor told me, because her son was “so full of holes.”

It took months for the entire story of Carlos’ death to emerge. The death certificate issued in March classified his death as a homicide, with the cause being “shot by prison/jail guards.” Several weeks later, Neven, the prison warden, overturned the murder and assault charges against Andrew Arevalo. He explained in a memo that while there was still “sufficient evidence” to find Arevalo guilty of killing Perez, he was downgrading the charges to battery. “Whether or not Inmate Perez was the initial aggressor, Inmate Arevalo's actions also contributed to this incident, as he continued to yell [and] kick,” Neven wrote. He reduced Arevalo’s sentence to 120 days in the hole. Victor does not blame Arevalo for his brother's death, “nor should he have to pay for it,” he says. “Is a chicken fight that much of a danger where you feel you had to shoot somebody?

There have been some changes at High Desert since the shooting. The three guards involved, Ramos, Castro and Smith, no longer work for the Nevada Department of Corrections, and the state attorney general is investigating the incident. None of the men have faced any charges. The director of the department at the time of Perez’s death, Greg Cox, abruptly resigned in September, because “the governor believed a change in leadership was necessary,” a spokesperson said. Neven, the High Desert warden, has been serving as acting deputy director of operations for the entire Nevada prison system since October. Meanwhile, the state legislature has approved the hiring of 100 more correctional officers for facilities throughout the state—an increase that falls far short of the 499 staffers recommended by ASCA. The NDOC also agreed to provide officers with better training on how to deal with unrest, and is equipping them with less harmful rubber stinger rounds to be used after the warning shot is fired.

One thing hasn’t changed, however. In September, ASCA’s independent corrections experts urged Nevada to phase out the use of birdshot. But the NDOC flatly refused. In a response, the department wrote that firing birdshot at prisoners has “stopped countless incidents that would have resulted in serious injury or death.” The method, NDOC insisted, is “less than lethal.”