In 1974, when she was only 14, Jackie Fuchs would wake up way before her parents and catch a ride with friends from her house in the San Fernando Valley across the Santa Monica Mountains and into Malibu. She’d hit the beach and paddle out in the quiet, pre-dawn dark.

It was the only time she could be on the water and not have to deal with the catcalls and the teasing, the good-natured gibes that gradually shaded into something harder and meaner. Before sunrise, she was just another surfer, her back to the sand, waiting for the right wave. She liked being the only girl out there.

Tall and slender with bright blue eyes and brown hair down to her shoulders, Jackie could have passed for Mary Tyler Moore’s daughter. The surfer dudes called her “Malibu Barbie.” One editor of a surfing magazine struck up a correspondence and sent her letters addressed to “Maliboobie.” “You had better get hot and send some good photos,” he wrote to her in black marker. “Your competition in photos is getting tough! You should see what some girls are sending in!” She could never tell how seriously to take the attention. In a letter to the editor published in June 1974, Jackie admonished one magazine for its skin-deep coverage of female surfers: “If they’re so hot, why don’t you show them surfing? Some of us chicks have more than just hot bods! Awoo!”

When Jackie heard that only male surfers were being paid to attend the national championships that year in North Carolina, she organized two benefit screenings of surf films to cover the travel expenses for female competitors. She cold-called directors to cajole them into donating reels of their documentaries for her events, and phoned local officials to arrange for fire permits, security and space. She passed out hundreds of homemade flyers up and down the Pacific Coast Highway. At the door, she took tickets until there wasn’t room left to stand. No one seemed to care how young she was.

“As rebellious as we thought we were,” says Steven Diamond, a childhood friend, “we were nothing compared to Jackie.” She was smarter and bolder than the other teenagers, constantly doing things girls were told they shouldn’t. She attended summer school just to take shop. She learned power chords on her Stratocaster and went to bed with the radio on, hoping to hear Fanny, the one all-female rock band in the universe, on KLOS. A middle school friend remembers driving to the grocery store with her mother one afternoon and spotting Jackie at the freeway on-ramp, her 6-foot-10-inch custom fiberglass swallowtail board under one arm and her thumb out.

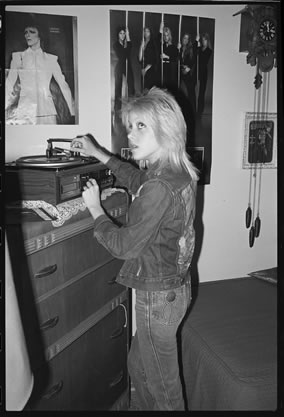

Jackie just wanted to find her own group of misfits. And since this was Los Angeles in the mid-’70s, that search ultimately led her to the Sunset Strip, where she could dance and discover new bands and feel at home among all the free spirits and Ziggy Stardust wannabes. “Sunset felt like the center,” recalls Victoria Lasken, a high school friend of Jackie’s. “That’s where you got to meet your tribe.”

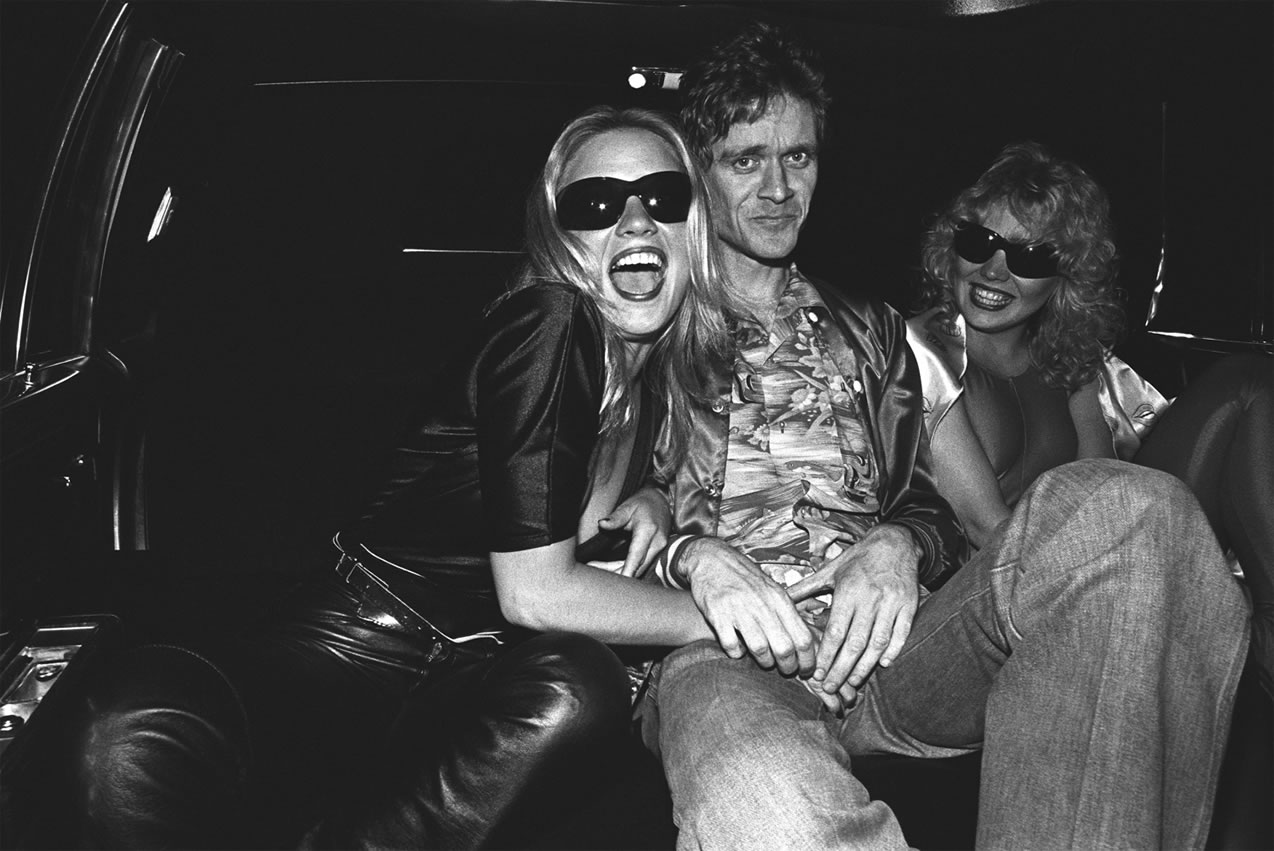

This was the Strip pre-paparazzi, pre-bodyguards with ear pieces, pre-20-member entourages, pre-AIDS, pre-everything. At the Rainbow Bar & Grill, you could find yourself sharing a pizza with Iggy Pop or listening to the members of Kiss hold court upstairs. At the Hyatt House (aka The Riot House), you could still pick up the lobby phone and call David Bowie’s room. It was like living inside the pages of Creem magazine.

One night in the spring of 1975, Rodney Bingenheimer, a notorious hanger-on and the unofficial mayor of the Sunset Strip, caught sight of Jackie and her friends on the dance floor at the Starwood. He’d been going around the room asking every girl whether she played an instrument. Jackie didn’t stand out. She was just next.

Jackie told him she played guitar, but when he wanted to know how old she was, she hesitated. “Why would anybody be interested in a 15-year-old musician?” she thought to herself.

When she finally fessed up, Bingenheimer squealed, “Oh, you’re perfect!” He told her there was this producer she had to meet—right now, in an apartment a short drive away—who was putting together an all-girl rock band. Maybe she’d like to be a part of it? Jackie had no idea what to say. She was giddy. She was dubious. She took along two friends as a precaution.

It was around 9 p.m. when they knocked on the door to Kim Fowley’s apartment, known as the Dog Palace. Immediately, Jackie saw that this was not some gilded pad of a record mogul. Spare change and scraps of paper scrawled with song lyrics carpeted the floor. Pill bottles covered a chest of drawers.

But Fowley was unashamed. He took one look at Jackie and went straight into a stream-of-consciousness pitch about his vision for her in the band. He spoke rapid-fire, his arms a blur, his fingers poking the air. “When the band is out together,” Fowley said, “they’ll wear heels and you won’t so you’ll all be the same height!”

“It’ll be a battle!” Fowley continued, “A battle between you and the drummer over who’s gonna be the leader of the band.” He paused before making it clear that there was a good chance the drummer would beat her up.

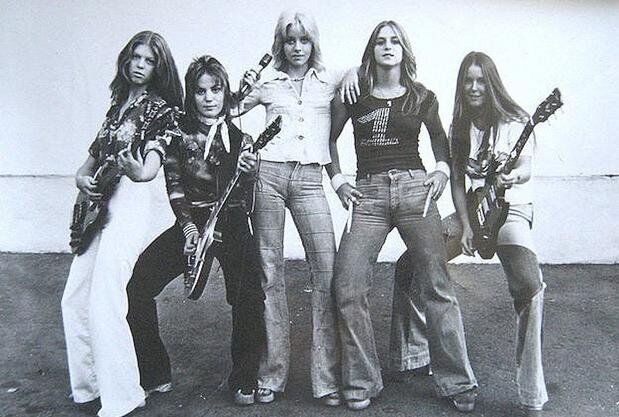

No one listening to Fowley at that moment could have predicted that the band he was describing, the Runaways, would have a lasting influence on pop culture and on feminism–that it would launch the careers of metal icon Lita Ford and Rock and Roll Hall of Famer Joan Jett, or that it would inspire the riot grrrl movement of the early ’90s, or that Kristen Stewart would later star in a biopic about the band. All Jackie knew on her first night at the Dog Palace was that she wanted in.

Within several months, she would have to decide whether to quit school to join the band. It should’ve been a harder choice. Jackie was a straight-A student who took the SAT following her freshman year and scored in the 98th percentile. She hoped to attend UCLA full-time during her senior year. But like a lot of overachievers, Jackie found high school dull and confining. “The Runaways represented this freedom,” Jackie says now. “I hated being in the box—‘be here at this time, do this at this time, do it this way.’ I just thought it would be better to speak my mind, sleep a little later, hang out and meet rock stars.”

After rejecting Jackie as lead guitarist, Fowley asked if she could play bass. She never had, but told him she would give it a try. The audition was the next day. She took three buses to get to the mobile home that served as the Runaways’ rehearsal space. There was old carpet on the floor and a shoddy P.A. system that never worked well enough to let anyone actually hear the vocals. Jackie plugged in and awkwardly started to pluck at her borrowed bass.

The other girls sensed she was a novice and didn’t like that she played with a pick. But Fowley told them that if they didn’t hire her, they’d have to cancel shows he had lined up. It would cost him money. One by one, the other band members—singer Cherie Currie, lead guitarist Lita Ford, rhythm guitarist and singer Joan Jett, and drummer Sandy West—voted her in. Jackie Fuchs became Jackie Fox—and Fowley became her boss, her mentor, her provider.

Jackie called her mom, Ronnie, with the good news. “But you don’t know how to play bass,” Ronnie protested. Jackie’s father was just as confused. Their skepticism faded after Fowley met with Ronnie at her home and explained his plans for Jackie and the band—how they would always have a bodyguard, a social worker and tutors with them. He stayed up with her until two in the morning, wheedling, counter-arguing, soothing. When he finally left, Ronnie had been worn down. “At that point I would have signed a contract for both my kids to be slaughtered in front of me,” Ronnie wrote her own parents immediately afterward.

To get ahead in the music business of the mid-’70s, to get your own Kiss Army and a chunk of that arena money, meant convincing a man you were worth it. If you wanted to get your band signed, a man had to approve the deal. If you wanted to cut a record, a man had to agree to produce it. Chances are, a man would decide whether to play your album’s first single on the radio and whether you got booked to play it live. And few tried to exploit this boys’ club more than Fowley.

His childhood was a difficult one—he said that he had polio and was raised in foster care. After a stint in a gang and then in the military, he discovered the music industry and studied it obsessively, longing to break in. He prided himself on working harder than everyone else. With characteristic indelicacy, he said he tried to do business “on a Jewish level.” There was always a next scheme, a new angle. He befriended studio engineers and label veeps, dialing A&R guys in London and never forgetting the name and complete discography of anyone even tangentially related to the industry.

On his runs through record label offices in Los Angeles, Fowley would lug a briefcase stuffed with song lyrics for every imaginable tune, more door-to-door salesman than Brill Building scribe. One folder was marked “folk rock lyrics,” another “heavy metal people.” He scoffed at musicians who thought songwriting was an art. When he met Bob Dylan in the mid-’60s, Fowley allegedly asked him, “What’s your gimmick? What’s your shtick?”

Fowley first scored big in 1960 with “Alley Oop,” a song inspired by a comic-strip caveman. Two years later, he had another hit with “Nut Rocker,” a rock version of Tchaikovsky’s “March of the Wooden Soldiers.” For the next 50 years, he jumped from stunt to stunt, landing in the liner notes of hundreds of albums, from hair-metal to country, Alice Cooper to Helen Reddy. Before he died from bladder cancer this January, he turned up in a wheelchair in a Beyoncé video.

“Of all the guys I know, he was married to rock and roll,” explains Chris Darrow, a musician who played on hundreds of records, including many of Fowley’s. “He was on duty 24 hours a day.”

Fowley had a phrase to describe his work—“doing the hustle”—and he applied it to all aspects of his life. He was sex-obsessed; it was a subject never far from his mind, a constant part of his patter. “In the ’70s, on a combination of beer and Quaaludes, you could take on a roomful of lesbians and tear them apart,” he was quoted as saying in the biography Queens of Noise: The Real Story of the Runaways. “The favorite sport then was squatting on a table and fucking as hard as you could when the beer and ’ludes hit, and then you would fall to the floor and roll around and come that way. That was the orgasm of choice in the ’70s for me.”

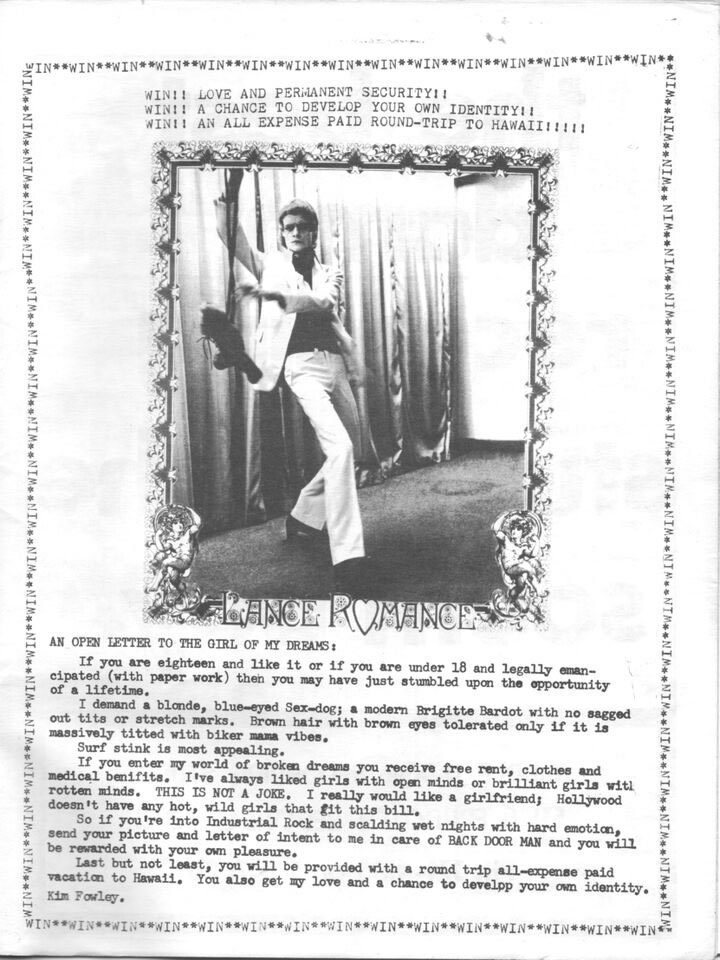

As he would admit to anyone, Fowley was mostly after teenage girls, or, in his words, “young cunt” or “dirty pussy.” In the June 1975 issue of Back Door Man, an influential L.A. ’zine, he spelled out his desires in a personal ad that included a cheesy photo of him in a white sport coat and white pants. It began, “If you are eighteen and like it or if you are under 18 and legally emancipated (with paper work) then you may have just stumbled upon the opportunity of a lifetime.”

The ad, which received zero responses, was an aberration. Fowley was rarely so passive in his pursuits. Steve Tetsch, a guitarist who worked with him on numerous projects and considered him a close friend, says they used to drive to high schools looking for teenage girls to hit on. “Westlake was a gold mine because these girls came from wealthy families,” he recalls. “We’d all be arrested today.”

As Fowley himself put it in Queens of Noise, describing his taste for vulnerable women: “I’m like a shark. I’ll smell the blood.”

The musicians and journalists who formed Fowley’s inner circle back then wanted to see his menace as an act, a test to weed out the weak. But some of his behavior was simply too violent to dismiss. In September 1975, Audrey Pavia, who had just turned 18, ended up backstage at an early Runaways show, when the band was just a trio. Without warning, Fowley ran at her from across the room.

“He threw me up against the wall and he put his arm across my neck,” Pavia remembers. “Then he hammered his knee between my legs.” Fowley lifted her up off the ground and licked her face. He bit and sucked on her ear. She says she struggled to get away, but he pinned her to the wall for five minutes, telling her all the things he was going to do to her.

“I was terrified. I was embarrassed,” Pavia says. “This is the part that’s most embarrassing for me. … I was a virgin. This was the most physical contact I’d had with a man.” Afterward, she noticed that her hair was matted with his spit.

Fowley could also come on slow, courting and grooming unsuspecting girls. In early 1975, he became enamored of Kari Krome, a 13-year-old aspiring songwriter he’d met at Alice Cooper’s birthday party. She was his type: a young girl who spent too much time dodging her violent stepdad and bouncing from apartment to apartment in various working-class neighborhoods. She sought refuge in the glam-rock scene, where her bisexuality was welcomed, and filled notebooks with songs that chronicled her experiences. “It wasn’t a hobby,” she explains. “I needed it like I needed to breathe.”

Soon, Fowley began calling her at night, instructing her to tell her mother that the calls were merely about business. They’d talk about music for hours; sometimes he’d play her a 45 over the phone and ask her what she thought about it. He told her she had good taste.

He insisted that they meet without her mother knowing. At a park near her home in Long Beach, Fowley brought Krome presents, including an Art Deco copper choker and a stack of the hippest 45s, magazines and T-shirts. It seemed to Krome that he had done this before.

On her 14th birthday, Krome’s mother took her to Fowley’s lawyer’s office so she could sign a contract: Krome would write songs for Fowley in return for $100 a month. She more than earned the money. It was Krome who discovered Joan Jett and convinced Fowley to start a band with her; she says he didn’t see Jett’s potential at first.

In a way, Fowley was the most responsible adult in her world. She needed him to believe in her, and he kept taking advantage of that. Months before Jackie joined the band, Krome and all the Runaways at the time crashed at the Dog Palace. Once everyone went to sleep, Krome says, Fowley walked into the living room and shook her awake. Before she could make a sound, he put a finger to his lips, shushing her. Then he grabbed her by her ankle and pulled her into the bedroom.

When Krome asked what was going on, he said something like, “It’s time for dog worship” and told her if she didn’t give in to his sexual demands, she’d have to go back to Long Beach. Krome thought about leaving, calling someone for a ride. But her family was poor and didn’t have a telephone. She had nowhere to go. That night, Fowley masturbated on her.

“I didn’t know how to say, ‘I don’t want you to do this,’” Krome says. “I did not have that voice. … I was also scared of him. He could be really scary.”

Fowley sexually assaulted her several other times, Krome says. “In his mind, he thought he was having a relationship with me, like a romantic relationship,” she says. “He didn’t care what I thought about it. He just decided.”

So many people in the industry knew what Fowley was like, what he was capable of. But he had just enough clout to convince the naïve and the desperate that he could make them stars. It was too risky to cross him.

Krome remembers waking up after the first incident and trying to talk to Jett and West. 1 “I told them he’s abusing me. I’m powerless, and I don’t know what to do,” Krome says. “They just looked at me blankly like I was the idiot. … I remember getting really mad and saying, ‘You know what? Watch your ass, because you might be next.’”

The final weeks of 1975 were madness for Jackie. She joined the Runaways, turned 16 and set out to learn the bass, all while attending class and preparing for her high school equivalency test. She also felt as if she had to win over the other band members, a bookworm among rockers in glitter shorts and leather. Rehearsals in the grungy Studio City trailer space could be tense and sometimes brutal affairs, depending on Fowley’s mood. During one of Jackie’s early practices, Fowley threw a microphone stand at the girls. “Come on, you dog cunts, play this piece of shit!” he screamed.

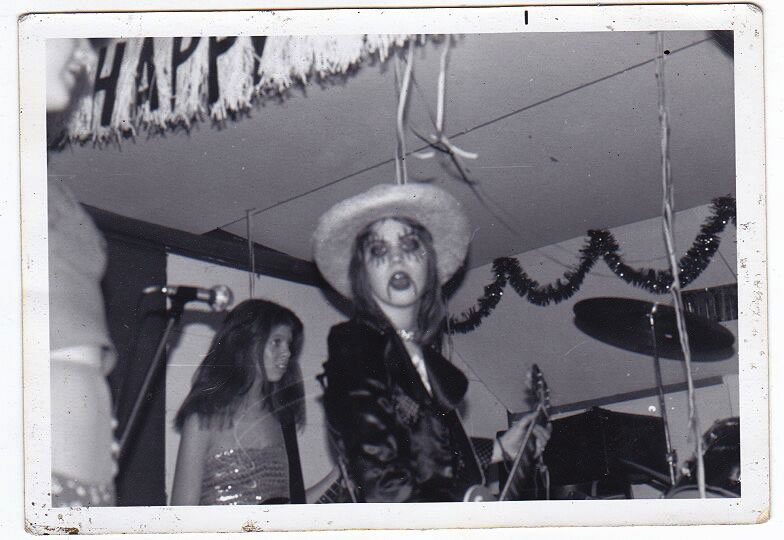

All the hard work was leading up to the Runaways’ New Year’s Eve show at a tiny club in Orange County called Wild Man Sam’s. The band didn’t have enough material for their four sets, so they filled the gaps with shouting contests, covers and unrehearsed jams. They yelled at each other to play slower; they needed to stretch out the time. In a photo taken during the final set, Jett is in full rock-star swagger mode: She’s wearing a giant straw hat, her face is painted up like a hollow-eyed scarecrow, her tongue’s sticking out. And there’s Jackie off to the side, looking petrified.

Jim Caron, who owned Wild Man Sam’s, remembers being impressed with the band that night, but also feeling uneasy about how young they all were. “Kim is not your regular, normal kind of guy,” he recalls. “It wasn’t like I could go up to Kim and say, ‘Dude, what are you going to do with the girls now that they are done playing? Are you going to take them home? Do they sleep in the studio? Do you keep them in a cage?’ He obviously had a lot of control over them.”

After the final set, at around 1 a.m., Fowley took the band to a drab motel near the club, where they started celebrating with friends. Jackie had thought of herself at the time as only a provisional member of the Runaways. Getting through the marathon show felt like a triumph. She’d seen so many kids her own age in the audience staring up at her. “It was an amazing feeling,” she says. “It was empowering.”

It was also short-lived. Soon after Jackie arrived at the motel, a grown man she thinks was a roadie approached her with a Quaalude in his hand. He told her she needed to take it, no questions asked. And she did. Another partygoer, Brent Williams, a friend of Krome’s, says he heard people (not members of the band) talking about the number of Quaaludes Jackie was being given that night—four, five, even six pills. “It was a date rape-type situation,” he says. Jackie has never before publicly discussed what happened next, once the drugs took hold, but it has changed the course of her life.

Most of the people at the party were teenagers, and they were spread out into different rooms. They smoked cigarettes and passed around beers. Jett played guitar with Williams; Krome smoked a joint with a guy outside. (Lita Ford was the one band member who said she wasn’t there, and witnesses say the same.)

When Helen Roessler and Trudie Arguelles, two of Jackie’s friends from the Sunset music scene, showed up, they couldn’t believe the state she was in. They had known her for a year and never once had they seen her intoxicated. “It didn’t seem OK,” Roessler says. “Jackie was always really in control.”

At some point, Jackie says she had to lie down on a bed to rest. She was having trouble staying upright. When a roadie checked to see if she was OK, Fowley asked him if he was interested in having sex with her. “She doesn’t mind,” Fowley said. “Do you?”

Jackie tried to protest, but she was frozen. “You don’t know what terror is until you realize something bad is about to happen to you and you can’t move a muscle,” she says. “I can’t move. I can’t speak. All I can do is look him in the eye and do the best I can do to communicate: Please say no. ... I don’t know what it looked like from the outside. But I know what was going on inside and it was horror.” The roadie declined Fowley’s offer, and soon after, Jackie says she started to slip in and out of consciousness.

According to Roessler, Fowley stood over Jackie and began to unbutton her blouse. Jackie wasn’t wearing a bra. “Nobody seemed to really care,” Roessler says. “It was really weird. Everybody was sitting in there alone with themselves. It felt like everyone was detached or trying to pretend like nothing was going on.”

But Roessler couldn’t stop staring at Fowley. She hoped he would notice her mute pleading, the rage in her eyes. “I remember really clearly just staring at him like, ‘If only I stare at him hard enough, it’ll make this all stop,’” Roessler says. “If only I stare at him and he looks at me, he’ll go, ‘Oh my God, what am I doing?’”

When Fowley started taking Jackie’s pants off, Roessler couldn’t bear it anymore. She got in her parents’ car and left. Around this time, Williams stumbled into the room. Multiple witnesses say that Fowley began to penetrate Jackie with the handle of a hairbrush. “It was one of those times you feel like there’s a spotlight on you,” Williams says. “Everybody’s looking at you to see how you would respond. You just want to get out of there.” And, soon enough, he did.

Fowley invited other guys to have sex with Jackie before removing his own pants and climbing on top of her. “Kim’s fucking someone!” a voice shouted from the door of the motel room to the partygoers outside, calling them in to watch. Arguelles returned to the room to see if this was all a big joke.

On the bed, Fowley played to the crowd, gnashing his teeth and growling like a dog as he raped Jackie. He got up at one point to strut around the room before returning to Jackie’s body.

“I remember opening my eyes, Kim Fowley was raping me, and there were people watching me,” Jackie says. She looked out from the bed and noticed Currie and Jett staring at her. She says this was her last memory of the night. Jett, through a representative, denied witnessing the event as it has been described here. Her representative referred all further questions to Jackie “as it’s a matter involving her and she can speak for herself.”

Currie claims that she spoke up and stormed out of the room. All witnesses say they felt intimidated. “It turned into this really disgusting Grand Guignol–like theater performance that he put on,” Krome says. “And Jackie was dead, dead, dead drunk—like corpse drunk. She was just laying down on her back, sound asleep, out of it.” Krome says Fowley picked up Jackie’s arm “and it flopped down like a marionette. … He had to manually move her body parts into positions that he wanted for himself.”

Krome escaped to the adjoining room and began drinking. She was confused why nobody did anything to end the attack. She recalls that Jett and Currie were sitting off to the side of the room for part of the time, snickering. “I didn’t know what to do,” she says. “Like what was I going to do? Go outside and drive and find a pay phone and call the police? I didn’t want to call the police on anyone, but at the same time I knew what was happening was wrong.” Krome was 14.

Jackie showed up at the next band practice some days later, not ready to stop being a Runaway. Although she was nervous about how her bandmates would treat her, she at least expected them to acknowledge that something bad had happened. But the girls hardly registered her presence. They just plugged in and started running through their songs. That was the day, Jackie says, “the elephant joined the band.”

Jackie took her bandmates’ silence to mean that she should keep quiet, too. “I didn’t know if anybody would have backed me,” she says. “I knew I would be treated horribly by the police—that I was going to be the one that ended up on trial more than Kim. I carried this sense of shame and of thinking it was somehow my fault for decades.”

Currie says the girls, who were then all 16 and 17, never talked about how to handle the rape. There was no decision or strategy. The unspoken rule was simply, “you forget it and you move on,” Currie explains. “I pushed it out of my mind the best I could.”

Jackie tried to do the same. She didn’t tell her parents what had happened. She did tell her sister Carol, who was just 13 at the time. Carol believes that Jackie “compartmentalized” the rape so that she could stay in the band.

That compartmentalization is painfully apparent in a photo of Jackie and Fowley taken in 1977. She’s draped around his neck, her bare leg straddling his waist. The pose is meant to be lascivious, but they’re both stiff and their expressions seem forced. By her reckoning, the photo was work: She had a job to do and she was doing it.

And the demands of the job were relentless. While the girls yearned to be taken seriously as musicians, Fowley insisted on selling them as hard-rock jailbait. He played up the youth angle every chance he got, recognizing that rebellious young women were craving self-expression and that male audiences found bad-girl fantasies appealing. Lusting after young girls simply wasn’t as taboo back then. This was an era when ZZ Top could sing about “my angelic teenage queen” or when a Virgin Islands ad campaign dared you to “Try a Virgin.” On the back of the Runaway’s debut album in 1976, Fowley listed each girl’s age next to her photo.

He dictated what the girls wore and how they moved on stage, going so far as to hire a choreographer—at the band’s expense—to teach Currie how to whip a microphone around on a cord and sling it up between her legs from behind. She howled ”Have you, and grab ya til you’re sore,” while wearing nothing but a white corset, black panties and fishnets. It was as iconic as Patti Smith belting out “Gloria” in a tie, but for a very different reason.

“He could be a jackass, but I understood what he was doing and what he was trying to tell everybody in his own Kim Fowley sort of way,” Lita Ford says. “He wanted us to be hot. He wanted us to have attitude and charisma.”

The rock press, for its part, saw the Runaways as little more than the teenage sluts of Fowley’s imagination. Headlines included “The Sex Kittens of Rock” and “Teenaged, Wild & Braless.” In a cover story for Crawdaddy, the author wrote that after seeing Currie perform “Cherry Bomb,” the band’s biggest song, he was “overcome with the urge to jack off against the stage.” A review in the April 1977 issue of Creem began with a simple three-word sentence: “These bitches suck.”

The mistrust between Jackie and everyone else associated with the Runaways made her quick-tempered and guarded. On long car rides between tour dates, Jackie refused to sleep, fearing that their driver would pass out. She made sure to stay sober on tour and complained when their manager, Scott Anderson, spent food money on drugs for the band. At a stop in Cleveland, Jackie vented to her family in a letter home: “I’m not at all sure I will last thru this tour what with the screaming, yelling & stupidity.”

The others—especially Ford—thought of Jackie as a charity case they were forced to hire, someone whose bass skills didn’t compensate for all the whining she did. In the 2004 Runaways documentary Edgeplay, Ford griped that Jackie was a hypochondriac who complained so much that “even my Noxzema made her sick.” Currie now believes that Fowley was manipulating the girls into hating one another. “We didn’t have anybody, a woman or anyone, to keep us talking or for us to be able to discuss things that were bothering us, if we felt that there was cruelty between the bandmates,” she says.

Jackie’s worrying and attempts at control made her stand out. “Jackie was very different from the other girls,” explains Kent Smythe, a roadie for the band. “She had a mouth on her.” Against the protestations of their booking agent, she tried to read and approve contracts for live shows. When Fowley wanted the girls to wear identical Runaways T-shirts with their names on them, as if they were a sports team or the female Ramones, Jackie objected. 2

She thought the band deserved better. One time, she says she went so far as to try to depose Fowley. She spent her own money to fly to New York, where she recruited Kiss’ manager to take over and Aerosmith’s producer to work on their next album. The coup attempt elicited nothing more than a shrug from the other girls. “What got to me was the band’s apathy toward everything,” she says. “You couldn’t get them interested in their own well-being.”

By the spring of 1977, Jackie told Jett that she’d had enough. But she says Jett got on her knees and begged her to stay—and a few weeks later, they set off on an extended tour through Japan, where they were legitimate stars. Hundreds of fans greeted the Runaways at the airport, and their days were filled with photo shoots and TV appearances. At their sold-out shows, Jackie was shocked to see as many women as men in the crowd, including a large number of teenage girls. “It was nice to have audiences that weren’t there primarily for the titillation factor,” Jackie says. After the tour, fans sent her letters saying how inspired they were. “I think I want to be a Rock musician like you,” one girl wrote. “I will find my own way.”

But dysfunction travels. During the soundcheck for one of the last shows in Japan, Jackie noticed that the stand she’d been given wasn’t strong enough to hold her white 1965 Gibson Thunderbird and alerted the crew. She treasured the instrument—it felt like one of the few things from her music career that was hers alone. It also cost $1,600.

When she rushed offstage after the main set, she found that the crew had blown off her request for a new stand. And when she went back out for the encore, a roadie handed her a different bass, saying that the Thunderbird had gone out of tune.

Jackie didn’t think much of it until the ride back to the hotel. The band and crew were acting weird around her, quiet and conspiratorial. It was a familiar feeling. Later in the evening, Smythe came by her room and told her that her beloved Thunderbird had fallen off the stand. Its head had snapped off.

When Smythe left, Jackie fell apart. She felt alone, like nobody gave a shit. She picked up a Coke bottle and whipped it against the wall, shattering it into pieces. She took one of the bigger shards and ran it down four inches of her forearm. “Then my anger was spent,” she says. “I dropped the glass.”

With Currie’s help, she made it to the hospital, where her arm was bandaged and she was given a sedative. Jackie checked in at some press events for the Runaways after that, but she realized what needed to be done: She called her mom and said, “get me out of here.” In no time, an envelope was waiting for her at the hotel’s front desk containing a bus ticket to the Tokyo airport. “If she wants to go home, let her go home,” Fowley told Smythe.

Shortly after Jackie returned to Los Angeles and the stories of her quitting the band hit the news, Brent Williams, who witnessed what happened to her the previous New Year’s, says he received a call from Jett. She said that Jackie’s parents might file a lawsuit. If lawyers ever contacted him, he needed to deny being in the motel room that night. (Jett’s representative did not comment when asked about the phone call.)

This was part of a pattern, Williams says. A day or two after the rape, Fowley made sure Williams attended a party of his in Hermosa Beach. There, Fowley warned him not to talk about what he'd seen. Fowley then asked Williams to pick up a guitar and gave him an on-the-spot songwriting lesson.

Fowley always denied any sexual impropriety with members of the Runaways, including in a 2013 band biography: “They can talk about it until the cows come home but, in my mind, I didn't make love to anybody in the Runaways nor did they make love to me.”

Victory Tischler-Blue was Jackie’s replacement on bass, and one of her main memories from her time as a Runaway was how some of the other members made fun of what happened to Jackie. “I heard about that nonstop,” she says now. “They would talk about Kim fucking Jackie like a dog. It was kind of a running joke.”

Oftentimes during soundchecks, Tischler-Blue says that Smythe would play his secret recording of Jackie’s breakdown in Japan. He made listening to it part of the band’s pre-show ritual. “He was taunting her and she started screaming, ‘I’m sick of being sick,’” Tischler-Blue remembers. “It became a catchphrase with the band. She was shrieking it. It shook me to my core—and everybody would laugh.”

A few months ago, I pulled up to a small, white house tucked away in the Hollywood Hills. Jackie greeted me from the shade of her doorway with a nervous smile and an apology about not having had time to put on makeup. It was the middle of the day, but she said she hadn’t been sleeping well. She needed tea. She led me through her house—which was spotless: the dining room had been partially converted to store cleaning supplies—toward the kitchen, where she grabbed a mug. “Now, what should we talk about first?” she asked.

She told me she never thought she’d go public with her rape, but last fall, she started seeing similar stories everywhere. More than a dozen women had come forward against Bill Cosby. Kesha filed a lawsuit alleging that she had been drugged and assaulted by her producer, Dr. Luke. 3 And there were so many undergraduate women who were finally speaking up about sexual assault. “I realized, ‘Oh my God, this is what’s happening on college campuses,’” she said.

Jackie saw herself in those young women and knew all the hurt and shame that awaited them. “They have to be making the same value judgments about themselves as I made about me,” she explained. “I know from personal experience how all those things can eat away at you. They can take vibrant young people and turn them into something else.”

After Jackie quit the band, returning to her mother’s house in the Valley felt like defeat. She sold her Thunderbird bass and never played in another band again. It made her feel too vulnerable. On the Sunset Strip, she was dogged by gossip about her breakdown in Japan. And most of her friends from high school were getting ready to go off to college; their lives had changed.

“It wasn’t like she could come back and be like, ‘Oh well, I’m in history class again,” says her childhood friend, Steven Diamond. She did record promotion and later took odd jobs, working as a used car salesman and selling toner cartridges over the phone. She auditioned for a role in This Is Spinal Tap as a confused groupie who puts both contact lenses in one eye.

Not until she enrolled at UCLA, in her mid-20s, did she start to seem more like her old, pre-Runaway self. In 1988, Jackie graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a combined major in linguistics and Italian and began studying at Harvard Law School, where she took all but one of her first year classes with Barack Obama. After earning her degree, she landed a series of well-paying jobs, mostly doing entertainment law for film studios and talent agencies. She vacationed in Italy and Morocco and took up photography. She bought a house.

Jackie thought she had come to terms with her rape or at least figured out how to live with it. “When something bad happens, you don’t go around thinking about it every day of your life,” she says. “You develop mechanisms to compensate for what has happened. I stuck it in a box in the attic and walled it in.”

Except, she says now, the rape had warped her life in ways she failed to recognize. She admits that intimacy is a constant struggle and that she’s barely dated since a brief marriage in the early ’90s. Sleep, always an issue for her, became more of one. The last time she dozed off feeling truly safe was 30 years ago. Just the memory of that rest on her grandmother’s couch in the middle of the day makes her cry. Also, because of the way the other Runaways had treated her, she carried this nagging feeling that maybe the rape was her fault. How could they have not supported her otherwise?

Jackie’s trauma intensified after learning in 2000 that Currie wanted to write about the rape for a memoir. Currie depicted the incident in lurid detail, but instead of Jackie, the victim was a fictionalized groupie who encouraged her rapist. Jackie was merely a bystander, and an indifferent one at that. Jackie threatened legal action over this account, at which point Currie collected affidavits from two witnesses. The publisher ultimately decided to pull the book, and Jackie continued to stay silent about what had happened to her. She wasn’t ready to come out as the true victim. 4

“The feelings of shame that I had felt before were now double-fold,” Jackie says.

Her guard only started to come down after reading Krome’s comments about the rape in a Runaways biography published two summers ago. Krome didn’t mention Jackie by name, but she didn’t need to. Krome’s account perfectly matched her memory.

This was a revelation. Jackie no longer wanted to push the rape as far out of her mind as possible; she wanted to know everything about it: Who else was in the room? Did they feel guilty about not intervening? Would she, in turn, feel guilty about that?

Jackie knew what she needed to do. She set about trying to track down Fowley. In the few times that Jackie had spoken to him on the phone years earlier, he would begin the conversation by asking if she was taping the call. Now, sick with bladder cancer, he brushed off her emails, and the number she had for him was disconnected.

Inspired by a lawsuit filed against Cosby by one of his alleged victims, she met with an attorney. She says she didn’t want money from Fowley; she just thought she might be able to scare him into a meeting. She craved an acknowledgement that what Fowley did was wrong, an apology. And if she didn’t get it, she knew precisely what to do: “I could have looked at him and said, ‘Don’t kid yourself that you’re dying in a state of grace. You’re going to die knowing you are not forgiven.’”

She never got that moment. Fowley died in mid-January and The New York Times hailed him as a “muse and talent scout of disposable art, a rogue conscience at the ground level of West Coast pop culture.” The obits, testimonials and tear-stained tweets, including some from her former bandmates, nauseated Jackie. But she didn’t dwell on her anger for long.

By then, Jackie had read up on a concept called “the bystander effect,” which seeks to explain why people who witness a crime often don’t do anything to stop it. The study of this phenomenon dates back to 1964, when Kitty Genovese, a New York City bar manager, was stabbed to death while her neighbors allegedly ignored her cries. Two social psychologists who examined that case, Bibb Latane and John Darley, observed that a violent crime doesn’t happen in slow motion. The perpetrator doesn’t have the decency to ask the crowd: So, how do you feel about this? It’s a witness’s job to decode the situation quickly, to tell if this is a violent act or something else.

As a result, bystanders don’t experience one dominant emotion. There’s anger, fear, worry for the victim, worry for themselves. It only gets more confusing when other bystanders are nearby; the more witnesses there are, the less likely it is that one of them will act. Latane and Darley call this “diffusion of responsibility.” Add in prevalent myths about rape, and the situation becomes even more complicated. A 2014 study found that witnesses were less likely to intervene in cases of sexual assault than iPod theft.

Jackie found herself becoming more understanding of the other people in the room. In December, she messaged Krome on Facebook: “We should talk one of these days. I think we have a lot to discuss.” Jackie made sure not to make the topic of conversation explicit; she knew that once she mentioned the rape in writing, she could never again pretend it didn’t happen. Krome replied with her number and an “xo.”

When Jackie finally called over a month later, it was only under the pretense of arranging a meeting. But they clicked instantly. Krome ended up telling Jackie everything she remembered from the night of the rape and then explained how her own life began to unravel soon after. In subsequent calls, Krome talked about how she dropped out of high school and became a full-blown addict, a real runaway. It took her years to get sober.

“I know that Jackie had a lot of pain,” Krome says. “I was glad to be able to tell her that you’re not crazy. It did happen. I just wanted her to know it was OK.”

A couple of months later, I met Krome outside her new apartment in a working class neighborhood about an hour south of Los Angeles. She was taking care of her girlfriend, who was laid up with a broken hip, and getting some paperwork together in order to collect disability benefits. Dinner that night was a liquor store sub.

Krome took me into her living room, still packed high with boxes, and explained that she had spent the last 40 years writing lyrics she never showed anybody. In the immediate aftermath of Jackie’s rape, she couldn’t shake the idea that Fowley never believed in her talent, that he only wanted to sleep with her. She ended up abandoning her dreams of becoming a successful songwriter. “I can’t blame Kim for my mistakes that I made in life,” Krome said. “But I know that incident really had an effect on me.”

Only now is she growing comfortable with the idea of sharing her work with others. When I asked to see the gray, palm-sized notebook she fills with song concepts and stray lyrics, she handed it over with little hesitation. About halfway through, there was a line that has stayed with me ever since. “Dear God,” she wrote in tiny script, “don’t throw me away.”

The conversation with Krome made Jackie feel more comfortable speaking openly about her rape. This Valentine’s Day, she asked to see a movie with her mother, Ronnie. Jackie had never told her what happened, in part because she knew how guilty it would make her mom feel—Ronnie had opened her home to Fowley all those years ago. “I was protecting her,” Jackie says. But outside a crowded frozen yogurt shop at the mall, with Girl Scouts selling cookies a few feet away, Jackie told her the whole story.

Ronnie said she suspected something had happened to Jackie during her time with the Runaways. She just didn’t know what. She teared up and hugged her daughter. They talked about how hard it was not to be emotional in public, and then they walked over to Macy’s. “It was a conversation that I’d always wanted to have with my mother,” Jackie told me later. “I think in part because I was calm when I was telling her.”

Carol worried that her sister’s new openness was re-traumatizing. Sure, Jackie had done well as a lawyer (she’s currently in between jobs) and amassed many friends over the years. But there were too many days when Jackie was alone in her house replaying it all. Had she been targeted? How many pills was she fed? How many people were in the room? How could anyone have believed it was anything but rape? 5 It was exhausting.

“She looks and sounds fragile,” Victoria Lasken, Jackie’s old high school friend, recalled after meeting her for the first time in years. “She speaks very quietly. I hugged her and I put my arms around her. She felt broken.”

Still, Jackie thought it was important to continue her detective work. She tracked down Roessler, who she discovered was also at the motel. Their friendship had been forged at Hollywood rock shows and on long bus rides to each other’s house, but they hadn’t spoken since the incident. “I feel like I’ve been waiting all this time to see her again,” Roessler says. “I never stopped thinking about the rape. Never.”

Roessler says what she saw in that room that night made her determined to become the anti-Jackie. She cut her arms and wrists and burned cigarettes into her hands. Friends gave her the nickname “Hellin Killer.” “I preferred dangerous,” she says. “It was safer to me. I will do shit that you don’t even want to know. …. If I’m going to fuck myself up this bad, what can you do?”

On a recent Sunday, Jackie invited Roessler and Arguelles, another witness, over to her house for a bad-movie night with some other friends. They shared vegan chicken salad and wine and didn’t talk about the rape once. “It was easy,” Jackie told me. “We were just hanging out. It was like a gathering of any friends.”

Sometimes Jackie wonders how her life, not to mention Krome’s and Roessler’s, would’ve been different had she never met Fowley or if she had found a ride home after the New Year’s Eve show. But she tries not to dwell. She says she’s more interested in restoring what’s been lost. “One of the things I've tried to do with every bystander is let them know it's not their fault,” she says. “I also have to not blame myself for what happened to them. We are all victims of what Kim did."