Why millennials are facing the scariest financial future of any generation since the Great Depression.

Like everyone in my generation, I am finding it increasingly difficult not to be scared about the future and angry about the past.

I am 35 years old—the oldest millennial, the first millennial—and for a decade now, I’ve been waiting for adulthood to kick in. My rent consumes nearly half my income, I haven’t had a steady job since Pluto was a planet and my savings are dwindling faster than the ice caps the baby boomers melted.

We’ve all heard the statistics. More millennials live with their parents than with roommates. We are delaying partner-marrying and house-buying and kid-having for longer than any previous generation. And, according to The Olds, our problems are all our fault: We got the wrong degree. We spend money we don’t have on things we don’t need. We still haven’t learned to code. We killed cereal and department stores and golf and napkins and lunch. Mention “millennial” to anyone over 40 and the word “entitlement” will come back at you within seconds, our own intergenerational game of Marco Polo.

This is what it feels like to be young now. Not only are we screwed, but we have to listen to lectures about our laziness and our participation trophies from the people who screwed us.

But generalizations about millennials, like those about any other arbitrarily defined group of 75 million people, fall apart under the slightest scrutiny. Contrary to the cliché, the vast majority of millennials did not go to college, do not work as baristas and cannot lean on their parents for help. Every stereotype of our generation applies only to the tiniest, richest, whitest sliver of young people. And the circumstances we live in are more dire than most people realize.

We've taken on at least 300% more student debt than our parents.

Source: The College Board, Trends in Student Aid 2013. Calculations based on average per-student borrowing in 1980 and 2010.

We're about 1/2 as likely own a home as young adults were in 1975.

Source: U.S. Census, young adults ages 24-35.

1 in 5 of us is living in poverty.

Source: U.S. Census, young adults ages 18-34.

Based on current trends, many of us won't be able to reture until we're 75.

Source: Projection for the class of 2015 based on a NerdWallet analysis of federal data.

But it’s not just the numbers.

What is different about us as individuals compared to previous generations is minor. What is different about the world around us is profound. Salaries have stagnated and entire sectors have cratered. At the same time, the cost of every prerequisite of a secure existence—education, housing and health care—has inflated into the stratosphere. From job security to the social safety net, all the structures that insulate us from ruin are eroding. And the opportunities leading to a middle-class life—the ones that boomers lucked into—are being lifted out of our reach. Add it all up and it’s no surprise that we’re the first generation in modern history to end up poorer than our parents.

This is why the touchstone experience of millennials, the thing that truly defines us, is not helicopter parenting or unpaid internships or Pokémon Go. It is uncertainty. “Some days I breathe and it feels like something is about to burst out of my chest,” says Jimmi Matsinger. “I’m 25 and I’m still in the same place I was when I earned minimum wage.” Four days a week she works at a dental office, Fridays she nannies, weekends she babysits. And still she couldn’t keep up with her rent, car lease and student loans. Earlier this year she had to borrow money to file for bankruptcy. I heard the same walls-closing-in anxiety from millennials around the country and across the income scale, from cashiers in Detroit to nurses in Seattle.

It’s tempting to look at the recession as the cause of all this, the Great Fuckening from which we are still waiting to recover. But what we are living through now, and what the recession merely accelerated, is a historic convergence of economic maladies, many of them decades in the making. Decision by decision, the economy has turned into a young people-screwing machine. And unless something changes, our calamity is going to become America’s.

Understanding structural disadvantage is pretty complicated. You’ll need a guide.

hat Scott remembers are the group interviews.

Eight, 10 people in suits, a circle of folding chairs, a chirpy HR rep with a clipboard. Each applicant telling her, one by one, in front of all the others, why he’s the right candidate for this $11-an-hour job as a bank teller.

It was 2010, and Scott had just graduated from college with a bachelor’s in economics, a minor in business and $30,000 in student debt. At some of the interviews he was by far the least qualified person in the room. The other applicants described their corporate jobs and listed off graduate degrees. Some looked like they were in their 50s. “One time the HR rep told us she did these three times a week,” Scott says. “And I just knew I was never going to get a job.”

After six months of applying and interviewing and never hearing back, Scott returned to his high school job at The Old Spaghetti Factory. After that he bounced around—selling suits at a Nordstrom outlet, cleaning carpets, waiting tables—until he learned that city bus drivers earn $22 an hour and get full benefits. He’s been doing that for a year now. It’s the most money he’s ever made. He still lives at home, chipping in a few hundred bucks every month to help his mom pay the rent.

In theory, Scott could apply for banking jobs again. But his degree is almost eight years old and he has no relevant experience. He sometimes considers getting a master’s, but that would mean walking away from his salary and benefits for two years and taking on another five digits of debt—just to snag an entry-level position, at the age of 30, that would pay less than he makes driving a bus. At his current job, he’ll be able to move out in six months. And pay off his student loans in 20 years.

There are millions of Scotts in the modern economy. “A lot of workers were just 18 at the wrong time,” says William Spriggs, an economics professor at Howard University and an assistant secretary for policy at the Department of Labor in the Obama administration. “Employers didn’t say, ‘Oops, we missed a generation. In 2008 we weren’t hiring graduates, let’s hire all the people we passed over.’ No, they hired the class of 2012.”

You can even see this in the statistics, a divot from 2008 to 2012 where millions of jobs and billions in earnings should be. In 2007, more than 50 percent of college graduates had a job offer lined up. For the class of 2009, fewer than 20 percent of them did. According to a 2010 study, every 1 percent uptick in the unemployment rate the year you graduate college means a 6 to 8 percent drop in your starting salary—a disadvantage that can linger for decades. The same study found that workers who graduated during the 1981 recession were still making less than their counterparts who graduated 10 years later. “Every recession,” Spriggs says, “creates these cohorts that never recover.”

The Class of Oh No

Heaven help you if you graduated on the wrong side of the recession.

’07 grad’09 gradOver 10 years, the typical ’09 grad could earn up to0less than the typical ’07 grad.

Sources: “Cashier or Consultant? Entry Labor Market Conditions, Field of Study, and Career Success,” by Joseph G. Altonji, Lisa B. Kahn & Jamin D. Speer, Journal of Labor Economics, 2016; and “The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy,” by Lisa B. Kahn, Labour Economics, 2010. Projections assume initial earnings of $50,000 and are based on the researchers' analysis of earnings during periods of growth and recession from 1980 to 2011.

By now, those unlucky millennials who graduated at the wrong time have cascaded downward through the economy. Some estimates show that 48 percent of workers with bachelor’s degrees are employed in jobs for which they’re overqualified. A university diploma has practically become a prerequisite for even the lowest-paying positions, just another piece of paper to flash in front of the hiring manager at Quiznos.

But the real victims of this credential inflation are the two-thirds of millennials who didn’t go to college. Since 2010, the economy has added 11.6 million jobs—and 11.5 million of them have gone to workers with at least some college education. In 2016, young workers with a high school diploma had roughly triple the unemployment rate and three and a half times the poverty rate of college grads.

Once you start tracing these trends backward, the recession starts to look less like a temporary setback and more like a culmination. Over the last 40 years, as politicians and parents and perky magazine listicles have been telling us to study hard and build our personal brands, the entire economy has transformed beneath us.

For decades, most of the job growth in America has been in low-wage, low-skilled, temporary and short-term jobs. The United States simply produces fewer and fewer of the kinds of jobs our parents had. This explains why the rates of “under-employment” among high school and college grads were rising steadily long before the recession. “The way to think about it,” says Jacob Hacker, a Yale political scientist and author of The Great Risk Shift, “is that there are waves in the economy, but the tide has been going out for a long time.”

The decline of the job has its primary origins in the 1970s, with a million little changes the boomers barely noticed. The Federal Reserve cracked down on inflation. Companies started paying executives in stock options. Pension funds invested in riskier assets. The cumulative result was money pouring into the stock market like jet fuel. Between 1960 and 2013, the average time that investors held stocks before flipping them went from eight years to around four months. Over roughly the same period, the financial sector became a sarlacc pit encompassing around a quarter of all corporate profits and completely warping companies’ incentives.

The pressure to deliver immediate returns became relentless. When stocks were long-term investments, shareholders let CEOs spend money on things like worker benefits because they contributed to the company’s long-term health. Once investors lost the ability to look beyond the next earnings report, however, any move that didn’t boost short-term profits was tantamount to treason.

The new paradigm took over corporate America. Private equity firms and commercial banks took corporations off the market, laid off or outsourced workers, then sold the businesses back to investors. In the 1980s alone, a quarter of the companies in the Fortune 500 were restructured. Companies were no longer single entities with responsibilities to their workers, retirees or communities.

Businesses applied the same chop-shop logic to their own operations. Executives came to see themselves as first and foremost in the shareholder-pleasing game. Higher staff salaries became luxuries to be slashed. Unions, the great negotiators of wages and benefits and the guarantors of severance pay, became enemy combatants. And eventually, employees themselves became liabilities. “Corporations decided that the fastest way to a higher stock price was hiring part-time workers, lowering wages and turning their existing employees into contractors,” says Rosemary Batt, a Cornell University economist.

Thirty years ago, she says, you could walk into any hotel in America and everyone in the building, from the cleaners to the security guards to the bartenders, was a direct hire, each worker on the same pay scale and enjoying the same benefits as everyone else. Today, they’re almost all indirect hires, employees of random, anonymous contracting companies: Laundry Inc., Rent-A-Guard Inc., Watery Margarita Inc. In 2015, the Government Accountability Office estimated that 40 percent of American workers were employed under some sort of “contingent” arrangement like this—from barbers to midwives to nuclear waste inspectors to symphony cellists. Since the downturn, the industry that has added the most jobs is not tech or retail or nursing. It is “temporary help services”—all the small, no-brand contractors who recruit workers and rent them out to bigger companies.

The effect of all this “domestic outsourcing”—and, let’s be honest, its actual purpose—is that workers get a lot less out of their jobs than they used to. One of Batt’s papers found that employees lose up to 40 percent of their salary when they’re “re-classified” as contractors. In 2013, the city of Memphis reportedly cut wages from $15 an hour to $10 after it fired its school bus drivers and forced them to reapply through a staffing agency. Some Walmart “lumpers,” the warehouse workers who carry boxes from trucks to shelves, have to show up every morning but only get paid if there’s enough work for them that day.

“This is what’s really driving wage inequality,” says David Weil, the former head of the Wage and Hour Division of the Department of Labor and the author of The Fissured Workplace. “By shifting tasks to contractors, companies pay a price for a service rather than wages for work. That means they don’t have to think about training, career advancement or benefit provision.”

This transformation is affecting the entire economy, but millennials are on its front lines. Where previous generations were able to amass years of solid experience and income in the old economy, many of us will spend our entire working lives intermittently employed in the new one. We’ll get less training and fewer opportunities to negotiate benefits through unions (which used to cover 1 in 3 workers and are now down to around 1 in 10). Plus, as Uber and its “gig economy” ilk perfect their algorithms, we’ll be increasingly at the mercy of companies that only want to pay us for the time we’re generating revenue and not a second more.

But the blame doesn’t only fall on companies. Trade groups have responded to the dwindling number of secure jobs by digging a moat around the few that are left. Over the last 30 years, they’ve successfully lobbied state governments to require occupational licenses for dozens of jobs that never used to need them. It makes sense: The harder it is to become a plumber, the fewer plumbers there will be and the more each of them can charge. Nearly a third of American workers now need some kind of state license to do their jobs, compared to less than 5 percent in 1950. In most other developed countries, you don’t need official permission to cut hair or pour drinks. Here, those jobs can require up to $20,000 in schooling and 2,100 hours of instruction and unpaid practice.

In sum, nearly every path to a stable income now demands tens of thousands of dollars before you get your first paycheck or have any idea whether you’ve chosen the right career path. “I was literally paying to work,” says Elena, a 29-year-old dietician in Texas. (I’ve changed the names of some of the people in this story because they don't want to get fired.) As part of her master’s degree, she was required to do a yearlong “internship” in a hospital. It was supposed to be training, but she says she worked the same hours and did the same tasks as paid staffers. “I took out an extra $20,000 in student loans to pay tuition for the year I was working for free,” she says.

All of these trends—the cost of education, the rise of contracting, the barriers to skilled occupations—add up to an economy that has deliberately shifted the risk of economic recession and industry disruption away from companies and onto individuals. For our parents, a job was a guarantee of a secure adulthood. For us, it is a gamble. And if we suffer a setback along the way, there’s so little to keep us from sliding into disaster.

Becoming poor is not an event. It is a process.

Like a plane crash, poverty is rarely caused by one thing going wrong. Usually, it is a series of misfortunes—a job loss, then a car accident, then an eviction—that interact and compound.

I heard the most acute description of how this happens from Anirudh Krishna, a Duke University professor who has, over the last 15 years, interviewed more than 1,000 people who fell into poverty and escaped it. He started in India and Kenya, but eventually, his grad students talked him into doing the same thing in North Carolina. The mechanism, he discovered, was the same.

We often think of poverty in America as a pool, a fixed portion of the population that remains destitute for years. In fact, Krishna says, poverty is more like a lake, with streams flowing steadily in and out all the time. “The number of people in danger of becoming poor is far larger than the number of people who are actually poor,” he says.

We’re all living in a state of permanent volatility. Between 1970 and 2002, the probability that a working-age American would unexpectedly lose at least half her family income more than doubled. And the danger is particularly severe for young people. In the 1970s, when the boomers were our age, young workers had a 24 percent chance of falling below the poverty line. By the 1990s, that had risen to 37 percent. And the numbers only seem to be getting worse. From 1979 to 2014, the poverty rate among young workers with only a high school diploma more than tripled, to 22 percent. “Millennials feel like they can lose everything at any time,” Hacker says. “And, increasingly, they can.”

Here’s what that downward slide looks like. Gabriel is 19 years old and lives in a small town in Oregon. He plays the piano and, until recently, was saving up to study music at an arts college. Last summer he was working at a health supplement company. It wasn’t the most glamorous job, lugging boxes and blending ingredients, but he made $12.50 an hour and he hoped he could step up to a better position if he proved himself.

Then his sister got into a car accident, T-boned turning into their driveway. “She couldn’t walk; she couldn’t think,” Gabriel says. His mom wasn't able to take a day off without risking losing her job, so Gabriel called his boss and left a message saying he had to miss work for a day to get his sister home from the hospital.

The next day, his temp agency called: He was fired. Though Gabriel says no one had told him, the company had a three-strikes policy for unplanned absences. He had already missed one day for a cold and another for a staph infection, so this was it. A former colleague told him that his absences meant he was unlikely to get a job there again.

So now Gabriel works at Taco Time and lives in a trailer with his mom and his sisters. Most of his paycheck goes to gas and groceries because his mom’s income is disappearing into the family’s medical bills. He still wants to go to college. But since he can barely keep his head above water, he’s set his sights on an electrician’s apprenticeship program offered by a local nonprofit. “I don’t understand why it’s so hard to do something with your life,” he tells me.

The answer is brutally simple. In an economy where wages are precarious and the safety net has been hacked into ribbons, one piece of bad luck can easily become a years-long struggle to get back to normal.

Over the last four decades, there has been a profound shift in the relationship between the government and its citizens. In The Age of Responsibility, Yascha Mounk, a political theorist, writes that before the 1980s, the idea of “responsibility” was understood as something each American owed to the people around them, a national project to keep the most vulnerable from falling below basic subsistence. Even Richard Nixon, not exactly known for lifting up the downtrodden, proposed a national welfare benefit and a version of a guaranteed income. But under Ronald Reagan and then Bill Clinton, the meaning of “responsibility” changed. It became individualized, a duty to earn the benefits your country offered you.

Since 1996, the percentage of poor families receiving cash assistance from the government has fallen from 68 percent to 23 percent. No state provides cash benefits that add up to the poverty line. Eligibility criteria have been surgically tightened, often with requirements that are counterproductive to actually escaping poverty. Take Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, which ostensibly supports poor families with children. Its predecessor (with a different acronym) had the goal of helping parents of kids under 7, usually through simple cash payments. These days, those benefits are explicitly geared toward getting mothers away from their children and into the workforce as soon as possible. A few states require women to enroll in training or start applying for jobs the day after they give birth.

The list goes on. Housing assistance, for many people the difference between losing a job and losing everything, has been slashed into oblivion. (To pick just one example, in 2014 Baltimore had 75,000 applicants for 1,500 rental vouchers.) Food stamps, the closest thing to universal benefits we have left, provide, on average, $1.40 per meal.

In what seems like some kind of perverse joke, nearly every form of welfare now available to young people is attached to traditional employment. Unemployment benefits and workers’ compensation are limited to employees. The only major expansions of welfare since 1980 have been to the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit, both of which pay wages back to workers who have already collected them.

Back when we had decent jobs and strong unions, it (kind of) made sense to provide things like health care and retirement savings through employer benefits. But now, for freelancers and temps and short-term contractors—i.e., us—those benefits might as well be Monopoly money. Forty-one percent of working millennials aren’t even eligible for retirement plans through their companies.

And then there’s health care.

In 1980, 4 out of 5 employees got health insurance through their jobs. Now, just over half of them do. Millennials can stay on our parents’ plans until we turn 26. But the cohort right afterward, 26- to 34-year-olds, has the highest uninsured rate in the country and millennials—alarmingly—have more collective medical debt than the boomers. Even Obamacare, one of the few expansions of the safety net since man walked on the moon, still leaves us out in the open. Millennials who can afford to buy plans on the exchanges face premiums (next year mine will be $388 a month), deductibles ($850) and out-of-pocket limits ($5,000) that, for many young people, are too high to absorb without help. And of the events that precipitate the spiral into poverty, according to Krishna, an injury or illness is the most common trigger.

“All of us are one life event away from losing everything,” says Ashley Lauber, a bankruptcy lawyer in Seattle and an Old Millennial like me. For most of her clients under 35, she says, the slide toward bankruptcy starts with a car accident or a medical bill. “You can’t afford your deductible, so you go to Moneytree and take out a loan for a few hundred bucks. Then you miss your payments and the collectors start calling you at work, telling your boss you can’t pay. Then he gets sick of it and he fires you and it all gets worse.” For a lot of her millennial clients, Lauber says, the difference between escaping debt and going bankrupt comes down to the only safety net they have—their parents.

But this fail-safe, like all the others, isn’t equally available to everyone. The wealth gap between white and non-white families is massive. Since basically forever, almost every avenue of wealth creation—higher education, homeownership, access to credit—has been denied to minorities through discrimination both obvious and invisible. And the disparity has only grown wider since the recession. From 2007 to 2010, black families’ retirement accounts shrank by 35 percent, whereas white families, who are more likely to have other sources of money, saw their accounts grow by 9 percent.

The result is that millennials of color are even more exposed to disaster than their peers. Many white millennials have an iceberg of accumulated wealth from their parents and grandparents that they can draw on for help with tuition, rent or a place to stay during an unpaid internship. According to the Institute on Assets and Social Policy, white Americans are five times more likely to receive an inheritance than black Americans—which can be enough to make a down payment on a house or pay off student loans. By contrast, 67 percent of black families and 71 percent of Latino families don’t have enough money saved to cover three months of living expenses.

And so, instead of receiving help from their families, millennials of color are more likely to be called on to provide it. Any extra income from a new job or a raise tends to get swallowed by bills or debts that many white millennials had help with. Four years after graduation, black college graduates have, on average, nearly twice as much student debt as their white counterparts and are three times more likely to be behind on payments. This financial undertow is captured in one staggering statistic: Every extra dollar of income earned by a middle-class white family generates $5.19 in new wealth. For black families, it’s 69 cents.

Arc of Injustice

The racial wealth gap isn't just glaring. It's growing.

Black WealthWhite WealthThe median white household will have1015166986more wealth than the median black household by 2020.

Sources: “The Road to Zero Wealth,” Institute for Policy Studies, September 2017 and “Household Wealth Trends In The United States, 1962-2013: What Happened Over the Great Recession?” National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2014.

Want to get even more depressed? Sit down and think about what’s going to happen to us when we get old. Despite all the stories you read about flighty millennials refusing to plan for retirement (as if our grandparents were obsessing over the details of their pension plans when they were 25), the biggest problem we face is not financial illiteracy. It is compound interest.

In the coming decades, the returns on 401(k) plans are expected to fall by half. According to an analysis by the Employee Benefit Research Institute, a drop in stock market returns of just 2 percentage points means a 25-year-old would have to contribute more than double the amount to her retirement savings that a boomer did. Oh, and she'll have to do it on lower wages. This scenario gets even more dire when you consider what's going to happen to Social Security by the time we make it to 65. There, too, it seems inevitable that we’re going to get screwed by demography: In 1950, there were 17 American workers to support each retiree. When millennials retire, there will be just two.

There’s one way that many Americans have traditionally managed to build wealth for themselves, to achieve some kind of dignity and comfort in old age. I’m talking, of course, about homeownership. At least we’ve got a shot at that, right?

Whenever Tyrone moves into a new apartment, he lies down naked on his living room floor.

It’s a ritual, a reminder of the years he spent without a floor underneath him or a ceiling above. He was homeless for four years in Georgia: sleeping on benches, biking to interviews in the heat, arriving an hour early so he wouldn’t be sweaty for the handshake. When he finally got a job, his co-workers found out that he washed himself in gas station bathrooms and made him so miserable he quit. “They said I ‘smelled homeless,’” he says.

Tyrone moved to Seattle six years ago, when he was 23, because he’d heard the minimum wage there was almost double what he made in Atlanta. He got a job at a grocery store and slept in a shelter while he saved. Since then, his income has gone up, but he’s been pushed farther and farther from the city. First stop was subsidized housing in Kirkland, 20 minutes east across the lake. Then a rented house in Tacoma, 45 minutes south, sharing a bedroom with his girlfriend and, eventually, a son. The breakup is why he’s now in Lakewood, even farther south, in a one-bedroom right next to a freeway entrance.

And it’s already such a strain. Tyrone earns $17 an hour as a security guard at a building site, his highest wage ever. But he’s a contractor (of course), so he doesn’t get sick leave or health insurance. His rent is $1,100 a month. It’s more than he can afford, but he could only find one building that would let him move in without paying the full deposit in advance.

Since rent is due on the 1st and he gets paid on the 7th, his landlord adds a $100 late fee to each month’s bill. After that and the car payments—it’s a two-hour bus ride from the suburb where he lives to the suburb where he works—he has $200 left over every month for food. The first time we met, it was the 27th of the month and Tyrone told me his account was already zeroed out. He had pawned his skateboard the previous night for gas money.

Despite the acres of news pages dedicated to the narrative that millennials refuse to grow up, there are twice as many young people like Tyrone—living on their own and earning less than $30,000 per year—as there are millennials living with their parents. The crisis of our generation cannot be separated from the crisis of affordable housing.

More people are renting homes than at any time since the late 1960s. But in the 40 years leading up to the recession, rents increased at more than twice the rate of incomes. Between 2001 and 2014, the number of “severely burdened” renters—households spending over half their incomes on rent—grew by more than 50 percent. Rather unsurprisingly, as housing prices have exploded, the number of 30- to 34-year-olds who own homes has plummeted.

Falling homeownership rates, on their own, aren’t necessarily a catastrophe. But our country has contrived an entire “Game of Life” sequence that hinges on being able to buy a home. You rent for a while to save up for a down payment, then you buy a starter home with your partner, then you move into a larger place and raise a family. Once you pay off the mortgage, your house is either an asset to sell or a cheap place to live in retirement. Fin.

This worked well when rents were low enough to save and homes were cheap enough to buy. In one of the most infuriating conversations I had for this article, my father breezily informed me that he bought his first house at 29. It was 1973, he had just moved to Seattle and his job as a university professor paid him (adjusted for inflation) around $76,000 a year. The house cost $124,000 — again, in today’s dollars. I am six years older now than my dad was then. I earn less than he did and the median home price in Seattle is around $730,000. My father’s first house cost him 20 months of his salary. My first house will cost more than 10 years of mine.

For a long time, that’s what cities did. They built upward, divided homes into apartments and added duplexes and townhomes.

But in the 1970s, they stopped building. Cities kept adding jobs and people. But they didn’t add more housing. And that’s when prices started to climb.

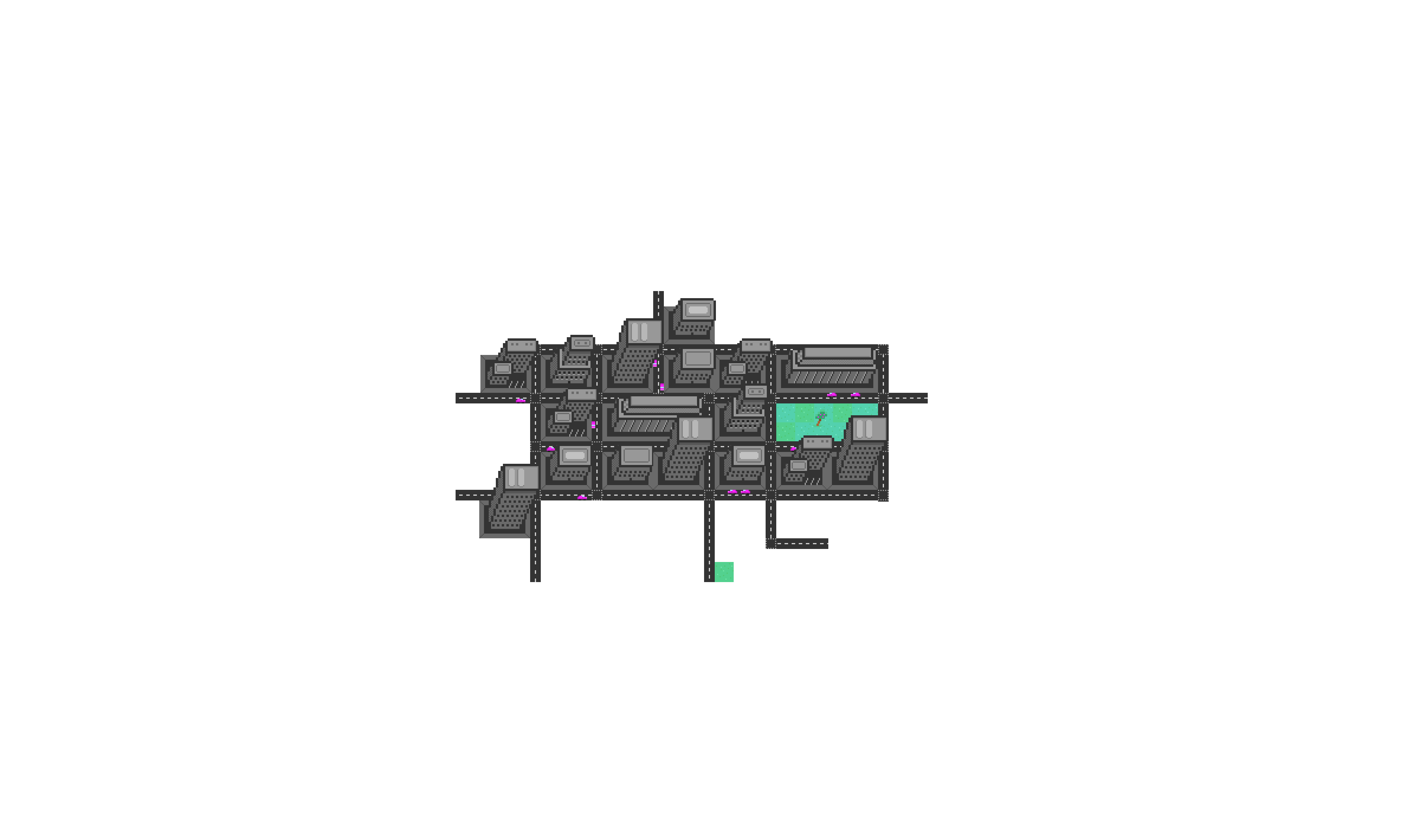

So much of this can be explained by one word:

At first, zoning was pretty modest. The point was to stop someone from buying your neighbor’s house and turning it into an oil refinery.

But eventually people realized they could use zoning for other purposes.

In the late 1960s, it finally became illegal to deny housing to minorities. So cities instituted weirdly specific rules that drove up the price of new houses and excluded poor people—who were, disproportionately, minorities.

Houses had to have massive backyards. They couldn’t be split into separate apartments. Basically, cities mandated McMansions.

We’re still living with that legacy. Across huge swaths of American cities, it’s pretty much illegal to build affordable housing.

And this problem is only getting worse.

That’s because all the urgency to build comes from people who need somewhere to live. But all the political power is held by people who already own homes.

For homeowners, there’s no such thing as a housing crisis.

Why?

Because when property values go up, so does their net worth. They have every reason to block new construction.

They do that by weaponizing environmental regulations and historical preservation rules.

They force buildings to be shorter so they don’t cast shadows. They demand two parking spaces for every single unit.

They complain that a new apartment building will destroy “neighborhood character” when the structure it’s replacing is… a parking garage. (True story.)

All this extra hassle means construction takes longer and costs more.

Which means that the only way most developers can make a profit is to build luxury condos.

So that’s why cities are so unaffordable. The entire system is structured to produce expensive housing when we desperately need the opposite.

The housing crisis in our most prosperous cities is now distorting the entire American economy. For most of the 20th century, the way many workers improved their financial fortunes was to move closer to opportunities. Rents were higher in the boomtowns, but so were wages.

Since the Great Recession, the “good” jobs—secure, non-temp, decent salary—have concentrated in cities like never before. America’s 100 largest metros have added 6 million jobs since the downturn. Rural areas, meanwhile, still have fewer jobs than they did in 2007. For young people trying to find work, moving to a major city is not an indulgence. It is a virtual necessity.

But the soaring rents in big cities are now canceling out the higher wages. Back in 1970, according to a Harvard study, an unskilled worker who moved from a low-income state to a high-income state kept 79 percent of his increased wages after he paid for housing. A worker who made the same move in 2010 kept just 36 percent. For the first time in U.S. history, says Daniel Shoag, one of the study’s co-authors, it no longer makes sense for an unskilled worker in Utah to head for New York in the hope of building a better life.

This leaves young people, especially those without a college degree, with an impossible choice. They can move to a city where there are good jobs but insane rents. Or they can move somewhere with low rents but few jobs that pay above the minimum wage.

This dilemma is feeding the inequality-generating woodchipper the U.S. economy has become. Rather than offering Americans a way to build wealth, cities are becoming concentrations of people who already have it. In the country’s 10 largest metros, residents earning more than $150,000 per year now outnumber those earning less than $30,000 per year.

Millennials who are able to relocate to these oases of opportunity get to enjoy their many advantages: better schools, more generous social services, more rungs on the career ladder to grab on to. Millennials who can’t afford to relocate to a big expensive city are … stuck. In 2016, the Census Bureau reported that young people were less likely to have lived at a different address a year earlier than at any time since 1963.

And so the real reason millennials can’t seem to achieve the adulthood our parents envisioned for us is that we’re trying to succeed within a system that no longer makes any sense. Homeownership and migration have been pitched to us as gateways to prosperity because, back when the boomers grew up, they were. But now, the rules have changed and we’re left playing a game that is impossible to win.

Which means

We start earning less money, later. We have more debt and higher rent.

we aren’t able to save.

we can’t buy a house or prepare for retirement.

that unless something changes…All of us are headed for a very dark place.

The most striking thing about the problems of millennials is how intertwined and self-reinforcing and everywhere they are.

Over the eight months I spent reporting this story, I spent a few evenings at a youth homeless shelter and met unpaid interns and gig-economy bike messengers saving for their first month of rent. During the days I interviewed people like Josh, a 33-year-old affordable housing developer who mentioned that his mother struggles to make ends meet as a contractor in a profession that used to be reliable government work. Every Thanksgiving, she reminds him that her retirement plan is a “401(j)”—J for Josh.

Fixing what has been done to us is going to take more than tinkering. Even if economic growth picks up and unemployment continues to fall, we’re still on a track toward ever more insecurity for young people. The “Leave It To Beaver” workforce, in which everyone has the same job from graduation until gold watch, is not coming back. Any attempt to recreate the economic conditions the boomers had is just sending lifeboats to a whirlpool.

But still, there is already a foot-long list of overdue federal policy changes that would at least begin to fortify our future and reknit the safety net. Even amid the awfulness of our political moment, we can start to build a platform to rally around. Raise the minimum wage and tie it to inflation. Roll back anti-union laws to give workers more leverage against companies that treat them as if they’re disposable. Tilt the tax code away from the wealthy. Right now, rich people can write off mortgage interest on their second home and expenses related to being a landlord or (I'm not kidding) owning a racehorse. The rest of us can’t even deduct student loans or the cost of getting an occupational license.

Some of the trendiest Big Policy Fixes these days are efforts to rebuild government services from the ground up. The ur-example is the Universal Basic Income, a no-questions-asked monthly cash payment to every single American. The idea is to establish a level of basic subsistence below which no one in a civilized country should be allowed to fall. The venture capital firm Y Combinator is planning a pilot program that would give $1,000 each month to 1,000 low- and middle-income participants. And while, yes, it’s inspiring that a pro-poor policy idea has won the support of D.C. wonks and Ayn Rand tech bros alike, it’s worth noting that existing programs like food stamps, TANF, public housing and government-subsidized day care are not inherently ineffective. They have been intentionally made so. It would be nice if the people excited by the shiny new programs would expend a little effort defending and expanding the ones we already have.

But they’re right about one thing: We’re going to need government structures that respond to the way we work now. “Portable benefits,” an idea that’s been bouncing around for years, attempts to break down the zero-sum distinction between full-time employees who get government-backed worker protections and independent contractors who get nothing. The way to solve this, when you think about it, is ridiculously simple: Attach benefits to work instead of jobs. The existing proposals vary, but the good ones are based on the same principle: For every hour you work, your boss chips in to a fund that pays out when you get sick, pregnant, old or fired. The fund follows you from job to job, and companies have to contribute to it whether you work there a day, a month or a year.

Small-scale versions of this idea have been offsetting the inherent insecurity of the gig economy since long before we called it that. Some construction workers have an “hour bank” that fills up when they’re working and provides benefits even when they’re between jobs. Hollywood actors and technical staff have health and pension plans that follow them from movie to movie. In both cases, the benefits are negotiated by unions, but they don’t have to be. Since 1962, California has offered “elective coverage” insurance that allows independent contractors to file for payouts if their kids get sick or if they get injured on the job. “The offloading of risks onto workers and families was not a natural occurrence,” says Hacker, the Yale political scientist. “It was a deliberate effort. And we can roll it back the same way.”

Another no-brainer experiment is to expand jobs programs. As decent opportunities have dwindled and wage inequality has soared, the government’s message to the poorest citizens has remained exactly the same: You’re not trying hard enough. But at the same time, the government has not actually attempted to give people jobs on a large scale since the 1970s.

Because most of us grew up in a world without them, jobs programs can sound overly ambitious or suspiciously Leninist. In fact, they’re neither. In 2010, as part of the stimulus, Mississippi launched a program that simply reimbursed employers for the wages they paid to eligible new hires—100 percent at first, then tapering down to 25 percent. The initiative primarily reached low-income mothers and the long-term unemployed. Nearly half of the recipients were under 30.

The results were impressive. For the average participant, the subsidized wages lasted only 13 weeks. Yet the year after the program ended, long-term unemployed workers were still earning nearly nine times more than they had the previous year. Either they kept the jobs they got through the subsidies or the experience helped them find something new. Plus, the program was a bargain. Subsidizing more than 3,000 jobs cost $22 million, which existing businesses doled out to workers who weren’t required to get special training. It wasn’t an isolated success, either. A Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality review of 15 jobs programs from the past four decades concluded that they were “a proven, promising, and underutilized tool for lifting up disadvantaged workers.” The review found that subsidizing employment raised wages and reduced long-term unemployment. Children of the participants even did better at school.

But before I get carried away listing urgent and obvious solutions for the plight of millennials, let’s pause for a bit of reality: Who are we kidding? Donald Trump, Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell are not interested in our innovative proposals to lift up the systemically disadvantaged. Their entire political agenda, from the Scrooge McDuck tax reform bill to the ongoing assassination attempt on Obamacare, is explicitly designed to turbocharge the forces that are causing this misery. Federally speaking, things are only going to get worse.

Which is why, for now, we need to take the fight to where we can win it.

Over the last decade, states and cities have made remarkable progress adapting to the new economy. Minimum-wage hikes have been passed by voters in nine states, even dark red rectangles like Nebraska and South Dakota. Following a long campaign by the Working Families Party and other activist organizations, eight states and the District of Columbia have instituted guaranteed sick leave. Bills to combat exploitative scheduling practices have been introduced in more than a dozen state legislatures. San Francisco now gives retail and fast-food workers the right to learn their schedules two weeks in advance and get compensated for sudden shift changes. Local initiatives are popular, effective and our best hope of preventing the country’s slide into “Mad Max”-style individualism.

The court system, the only branch of our government currently functioning, offers other encouraging avenues. Class-action lawsuits and state and federal investigations have resulted in a wave of judgments against companies that “misclassify” their workers as contractors. FedEx, which requires some of its drivers to buy their own trucks and then work as independent contractors, recently reached a $227 million settlement with more than 12,000 plaintiffs in 19 states. In 2014, a startup called Hello Alfred—Uber for chores, basically—announced that it would rely exclusively on direct hires instead of “1099s.” Part of the reason, its CEO told Fast Company, was that the legal and financial risk of relying on contractors had gotten too high. A tsunami of similar lawsuits over working conditions and wage theft would be enough to force the same calculation onto every CEO in America.

And then there’s housing, where the potential—and necessity—of local action is obvious. This doesn’t just mean showing up to city council hearings to drown out the NIMBYs (though let’s definitely do that). It also means ensuring that the entire system for approving new construction doesn’t prioritize homeowners at the expense of everyone else. Right now, permitting processes examine, in excruciating detail, how one new building will affect rents, noise, traffic, parking, shadows and squirrel populations. But they never investigate the consequences of not building anything—rising prices, displaced renters, low-wage workers commuting hours from outside the sprawl.

Some cities are finally acknowledging this reality. Portland and Denver have sped up approvals and streamlined permitting. In 2016, Seattle’s mayor announced that the city would cut ties with its mostly old, mostly white, very NIMBY district councils and establish a “community involvement commission.” The name is terrible, obviously, but the mandate is groundbreaking: Include renters, the poor, ethnic minorities—and everyone else unable to attend a consultation at 2 p.m. on a Wednesday—in construction decisions. For decades, politicians have been terrified of making the slightest twitch that might upset homeowners. But with renters now outnumbering owners in nine of America’s 11 largest cities, we have the potential to be a powerful political constituency.

The same logic could be applied to our entire generation. In 2018, there will be more millennials than boomers in the voting-age population. The problem, as you’ve already heard a million times, is that we don’t vote enough. Only 49 percent of Americans ages 18 to 35 turned out to vote in the last presidential election, compared to about 70 percent of boomers and Greatests. (It’s lower in midterm elections and positively dire in primaries.)

But like everything about millennials, once you dig into the numbers you find a more complicated story. Youth turnout is low, sure, but not universally. In 2012, it ranged from 68 percent in Mississippi (!) to 24 percent in West Virginia. And across the country, younger Americans who are registered to vote show up at the polls nearly as often as older Americans.

The fact is, it’s simply harder for us to vote. Consider that nearly half of millennials are minorities and that voter suppression efforts are laser-focused on blacks and Latinos. Or that the states with the simplest registration procedures have youth turnout rates significantly higher than the national average. (In Oregon it’s automatic, in Idaho you can do it the same day you vote and in North Dakota you don’t have to register at all.) Adopting voting rights as a cause—forcing politicians to listen to us like they do to the boomers—is the only way we’re ever going to get a shot at creating our own New Deal.

Or, as Shaun Scott, the author of Millennials and the Moments That Made Us, told me, “We can either do politics or we can have politics done to us.”

And that’s exactly it. The boomer-benefiting system we’ve inherited was not inevitable and it is not irreversible. There is still a choice here. For the generations ahead of us, it is whether to pass down some of the opportunities they enjoyed in their youth or to continue hoarding them. Since 1989, the median wealth of families headed by someone over 62 has increased 40 percent. The median wealth of families headed by someone under 40 has decreased by 28 percent. Boomers, it's up to you: Do you want your children to have decent jobs and places to live and a non-Dickensian old age? Or do you want lower taxes and more parking?

Then there’s our responsibility. We’re used to feeling helpless because for most of our lives we’ve been subject to huge forces beyond our control. But pretty soon, we’ll actually be in charge. And the question, as we age into power, is whether our children will one day write the same article about us. We can let our economic infrastructure keep disintegrating and wait to see if the rising seas get us before our social contract dies. Or we can build an equitable future that reflects our values and our demographics and all the chances we wish we'd had. Maybe that sounds naïve, and maybe it is. But I think we're entitled to it.

Credits

He is also a part of the lettering sketch blog Friends of Type.