The Super Predators

When the man who abuses you is also a cop.

The Super Predators

When the man who abuses you is also a cop.

Story by and

Illustrations by Simon Prades

All Sarah Loiselle wanted was a carefree summer. There was no particular reason she was feeling restless, but she’d been single for about a year and her job working with cardiac patients in upstate New York could be intense. So when she learned that a Delaware hospital needed temporary nurses, she leapt at the chance to spend a summer by the beach. In June 2011, the tall, bubbly 32-year-old drove her Jeep into the sleepy coastal town of Lewes. She and her poodle, Aries, moved into a rustic apartment above a curiosity shop that once housed the town jail. The place was so close to the bay that she could go sunbathing on her days off. It didn’t bother Loiselle that she’d be away from her friends and family for a while: She felt like she’d put her real life on hold, that she was blissfully free of all her responsibilities.

And then she met a guy. She’d never dated online before, but an acquaintance convinced her to try a site called PlentyOfFish. Loiselle, who has a slender face framed by auburn hair, soon found herself messaging with 36-year-old Andrel Martinez, a muscular Delaware state trooper. She was intrigued enough to drive an hour with him to Ocean City, Maryland, for what she thought was a great date: They had dinner, strolled along the beach and danced at a waterfront club. Right away she noticed Martinez’s height (he is more than 6 feet tall) and the way he carried himself, with a confidence she would come to associate with cops. Loiselle was hardly a meek person, but his presence made her feel safe. She thought it was sweet when he reached back through a crowd to take her hand.

They started seeing each other regularly. And as the summer went by, Loiselle began to feel like she could really trust him. One night over dinner, she talked about her family. Loiselle had left home young, after she’d become pregnant at 18. She’d placed her baby up for adoption—but she was proud that she was still in touch with her daughter, whose birthday was tattooed on her hip. That night, Loiselle said, Martinez got choked up and said he loved her and wanted to be with her so they could turn their lives “into something beautiful.” When her contract was up at the end of the summer, Loiselle found a new job and stayed in Delaware.

Sarah Loiselle felt like she could really trust Andrel Martinez.

PAULA BAIRD MIGNOGNO

Sarah Loiselle felt like she could really trust Andrel Martinez.

PAULA BAIRD MIGNOGNO

They moved in together, talked about having a child. But as the months grew colder, doubts crept in. Some of Loiselle’s new friends found Martinez overbearing. Stephanie Botti, whom she met through work, went to a club with the new couple and recalled Martinez “getting all weird about these guys who want nothing to do with us,” inserting himself between them with “aggressive body language.” Loiselle noticed that he seemed to be constantly questioning her or telling her what to do—probably a cop thing, she figured. And she didn’t like it when, she said, Martinez would talk disparagingly about her daughter’s adoption. By the winter, she wasn’t sure if she wanted to break up with him. But she thought it might be a good idea to check out a few apartments, just in case.

She was on her way to look at a place when Martinez called. Loiselle came up with some cover story, but when she got home, she said, his police car was parked in the driveway. That surprised her, because she’d thought he was supposed to be at work. When she walked into the darkened kitchen, she said, she found Martinez standing there, his hands resting on his gun belt. “Where were you?” he asked. Before she could answer, she said, he made a comment about the very building she’d just visited. He said he’d just happened to see her there. That was when she realized that leaving him might be harder than she’d anticipated.

He would stand and stare at her, using what she called his “interrogation voice.”

When Loiselle discovered she was pregnant, in January 2012, she decided to try to make the relationship work. But Martinez “had this expectation of the woman of the house,” she said. “He wanted me to be super fun and hot and sexy and meet all of his needs. I was pregnant and felt like crap.” At one point, she said, Martinez gave her a self-help book for police wives. The message seemed pretty obvious to her: She needed to get in line, to be more supportive of her man.

In September they had a daughter, whom we’ll call Jasmine. But after the birth, Loiselle and Martinez fought a lot. Martinez has said that Loiselle would belittle him and call him worthless. Loiselle’s friends, meanwhile, thought he was controlling. She “needed to do what he wanted her to do,” Botti observed. “Otherwise he was going to escalate.” Another friend, Danielle Gilbert, said, “If Sarah was somewhere with me, he would have to know where she was, or if she didn’t tell him, he would find out, which I found really odd. I was like, ‘Does he have somebody spying on you? Is he spying on you?’”

- 07/18/12: Sarah Loiselle

Loiselle was increasingly unnerved by how quickly Martinez could swing from sweet and loving to angry and sullen. On one occasion, she said, he held her down and dug his fingers into her neck to demonstrate pressure points. When she started crying and asked him to stop, he laughed, saying he was just playing around, she recalled. He called her a “motherfucking cunt” or a “bitch,” she said, and would stand and stare at her, using what she called his “interrogation voice.” She believed he knew precisely how much pressure, mental or physical, he needed to exert to make her do exactly what he wanted. And she had a gnawing fear of what might happen if she didn’t comply.

If domestic abuse is one of the most underreported crimes, domestic abuse by police officers is virtually an invisible one. It is frighteningly difficult to track or prevent—and it has escaped America’s most recent awakening to the many ways in which some police misuse their considerable powers. Very few people in the United States understand what really happens when an officer is accused of harassing, stalking, or assaulting a partner. One person who knows more than most is a 62-year-old retired cop named Mark Wynn.

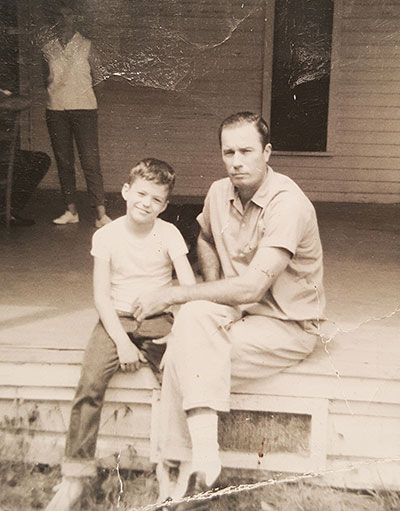

Wynn decided to be a police officer when he was about 5 years old because he wanted to put his stepfather in prison. Alvin Griffin was a violent alcoholic who terrorized Wynn’s mother, a waitress and supermarket butcher. Looking back, Wynn compares his childhood in Dallas to living inside a crime scene. “There was always blood in my house,” he said.

The cops sometimes showed up, usually after a neighbor called to complain about the screaming, but they didn’t do much. Wynn doesn’t remember them ever talking to him or his four siblings. He does remember clinging to his mother while a police officer threatened to arrest her if they had to come back to the house again. “There was no one to help us,” he said. “We were completely isolated.” Wynn has often spoken of the time he tried to kill his stepfather when he was 7—how he and his brother emptied out the Mad Dog wine on Griffin’s bedside dresser and replaced it with Black Flag bug spray. A few hours later, Griffin downed the bottle as the boys waited in the living room. Griffin didn’t seem to notice anything wrong with the wine. But he didn’t die, either.

Years later, when Wynn was around 13 and all but one of his siblings had left home, he was watching television when he heard a loud crack that sounded like a gunshot. He found his mother splayed on the floor of their tiny kitchen, blood pooling around her face. Griffin had knocked her out with a punch to the head. Wynn watched as Griffin stepped over her, opened the fridge, pulled out a can of beer and drank it. That night, Griffin got locked up for public drunkenness and Wynn, his sister and his mother finally got out, driving to Tennessee with a few belongings. Griffin never found them.

Mark Wynn with his stepfather, Alvin Griffin, in 1961. COURTESY OF MARK WYNN

Mark Wynn with his stepfather, Alvin Griffin, in 1961. COURTESY OF MARK WYNN

Wynn became a police officer in the late 1970s and after a few years, he wound up in Nashville. Then as now, domestic complaints tended to be one of the most common calls fielded by police. And Wynn was disturbed to find that he was expected to handle them in much the same way as the cops from his childhood had—treat it as a family matter, don’t get involved. He remembers that officers would write cursory summaries on 3 by 5 inch “miscellaneous incident” cards rather than full reports. To fit what he regarded as essential details in the tiny space provided, Wynn would print “really, really small,” he said. “The officers I worked with used to get pissed off at me,” he added. They couldn’t understand why he bothered.

But Wynn had entered the force at a pivotal moment. In the late 1970s, women’s groups had turned domestic violence into a major national cause, and abused women successfully sued police departments for failing to protect them. Over the next decade, states passed legislation empowering police to make arrests in domestic incidents and to enforce protective orders. Wynn eagerly embraced these changes and in the late 1980s, the Department of Justice asked him to train police chiefs on best practices. He went on to lead one of the country’s first specialized investigative units for family violence. By the passage of the 1994 Violence Against Women Act, which poured more than $1 billion into shelters and law enforcement training, the U.S. was finally starting to treat domestic violence as a crime. “It was like stepping out of the Dark Ages,” Wynn said.

And yet when officers themselves were the accused, cases tended to be handled in the old way. Wynn would hear stories around his station, like an assailant who received a quiet talk from a colleague instead of being arrested. “Officers thought they were taking care of their fellow officer,” said David Thomas, a former police officer and a consultant for the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP). “But what they were doing was colluding with a criminal.”

It is nearly impossible to calculate the frequency of domestic crimes committed by police—not least because victims are often reluctant to seek help from their abuser’s colleagues. Another complication is the 1996 Lautenberg Amendment, a federal law that prohibits anyone convicted of misdemeanor domestic abuse from owning a gun. The amendment is a valuable protection for most women. But a police officer who can’t use a gun can’t work—and so reporting him may risk the family’s livelihood as well as the abuser’s anger. Courts can be perilous to navigate, too, since police intimately understand their workings and often have relationships with prosecutors and judges. Police are also some of the only people who know the confidential locations of shelters. Diane Wetendorf, a domestic violence counselor who wrote a handbook for women whose abusers work in law enforcement, believes they are among the most vulnerable victims in the country.

For more stories that stay with you, subscribe to our newsletter.

In 1991, a researcher at Arizona State University testified to a congressional committee about a survey she’d conducted of more than 700 police officers. Forty percent admitted that they had “behaved violently against their spouse and children” in the past six months (although the study didn’t define “violence.”) In a 1992 survey of 385 male officers, 28 percent admitted to acts of physical aggression against a spouse in the last year—including pushing, kicking, hitting, strangling and using a knife or gun. Both studies cautioned that the real numbers could be even higher; there has been startlingly little research since.

Even counting arrests of officers for domestic crimes is no simple undertaking, because there are no government statistics. Jonathan Blanks, a Cato Institute researcher who publishes a daily roundup of police misconduct, said that in the thousands of news reports he has compiled, domestic violence is “the most common violent crime for which police officers are arrested.” And yet most of the arrested officers appear to keep their jobs.

Philip Stinson, an associate professor of criminal justice at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, uses an elaborate set of Google news alerts to identify arrests of law enforcement personnel and then attempts to track the outcome through news reports and court records. Between 2005 and 2012, he found 1,143 cases in which an officer was arrested for a crime of domestic violence. While he emphasized that his data is incomplete, he discovered convictions in only 30 percent of the cases. In 38 percent, officers either resigned or were fired and in 17 percent, he found no evidence of adverse consequences at all. Stinson noted that it wasn’t uncommon for police to be extended a “professional courtesy” in the form of a lesser charge that might help them avoid the Lautenberg Amendment. Officers could be booked for disorderly conduct instead of domestic assault. If they were charged with domestic violence, the prosecutor might allow them to plead to a different offense. Stinson has identified dozens of officers who are still working even after being convicted.

Through public records requests, we also obtained hundreds of internal domestic abuse complaints made about police officers between 2014 and 2016 in 8 of the 10 largest cities in the country. Officers can be penalized internally whether or not criminal charges are filed—although the penalties may be minor and many complaints are not substantiated. An ABC 7 investigation this February found that nine of every 10 domestic violence allegations made against Chicago police officers by spouses or children resulted in no disciplinary action.

What is striking in many of the internal complaints, as well as incidents we found in news reports, is the degree of alleged violence and how often it appears to coincide with the misuse of police authority. An officer in New Jersey was indicted in January after he allegedly used his identification to enter the hotel room of a woman he was dating, fired a gun in her direction, assaulted her to get her to recant a statement, and attacked an officer who was working with investigators. He pleaded not guilty. So did a veteran Cleveland officer who was arrested the same month for allegedly beating his girlfriend with his service gun, firing shots near her head, then sexually assaulting her at gunpoint. Last September, an officer in Indiana was arrested for assaulting his ex-girlfriend for years—after previously alleging that she had abused him. (The case has not yet gone to trial.) And in 2013, a San Antonio police officer allegedly hit his wife with a gun and pointed it at his children. He ultimately pleaded no-contest to “making an obscene gesture.” Because he was not convicted of a domestic violence offense, he kept his officer’s license.

Despite the scarcity of data, the IACP has acknowledged that domestic violence is likely “at least” as prevalent within police families as in the general population. Which is significant: One third of women are estimated to experience sexual or physical violence or stalking by a partner during their lifetime. This is why, since the late 1990s, Wynn has focused on exposing the problem of abusive officers and persuading police departments to address it. As he sees it, the issue triggers every possible defensive instinct a cop might possess: romantic, protective, fraternal, tribal: “It’s the last frontier of policing.”

The first time that Sarah Loiselle tried to get help was March 21, 2013. Some days earlier, she’d been preparing to give Jasmine a bath. Then, she said, Martinez informed her that he wanted to do it. By her account, he took the baby from her arms and, when she tried to follow him into the bathroom, pushed her out and shut the door. It felt to her like he was demonstrating that he was in total control. Around this time, she emailed a therapist the couple had been seeing. “[I am] starting to become afraid for our safety and going to separate from him,” she wrote. After she quietly moved the base of Jasmine’s car seat out of Martinez’s vehicle, she said, he started questioning her in his interrogation voice again: What did you go outside for? Where are you going to go? That night, she lay in bed in the guest room, heart pounding. “It’s like a grizzly is in front of you,” she recalled. “Get down, cover your head with your hands and hope he stops.” She left with Jasmine the next morning while Martinez was still sleeping and went straight to the family courthouse.

There, staff explained Loiselle’s options: Under Delaware law, the state could confiscate Martinez’s firearms if she were granted a protective order. Afraid of making him even angrier if something happened to his job, she decided not to file. That night, she sent him a text message:

In another message he added:

The next day, Loiselle was blindsided when Martinez filed for emergency custody of Jasmine. He called Loiselle emotionally unstable and said he was worried for his daughter’s safety. Among other things, he cited the fact that Loiselle had placed her first child up for adoption. Loiselle filed for a protective order, describing the bathroom incident and other behavior that had made her frightened to stay with him. (She later detailed her allegation that he used pressure points on her in a separate proceeding.) Eventually, she dropped her petition in exchange for 50-50 custody of Jasmine, she said.

For a while, Loiselle stayed with a friend, Paula Mignogno, who recalled that they tried to park Loiselle’s car where it couldn’t be seen from the road. But then Loiselle started hearing from various people that Martinez was looking for her. He showed up in uniform at the hospital where she used to work, according to a nurse who asked not to be named out of concern for her safety. As a police officer, Martinez was able to get into the ER, where the nurse said he cornered her in a utility room full of soiled linens and demanded to know where Loiselle and Jasmine were. She pushed past him, she said, and Martinez followed, yelling that he would find out one way or another. Feeling threatened, the nurse contacted Martinez’s station. “I was basically told that this was a domestic issue, it has nothing to do with his job, it has nothing to do with Delaware State Police,” she said.

- 04/30/13: Sarah Loiselle

By April 2013, Loiselle was living about a five-minute drive from Martinez’s house. She’d chosen the location so they could exchange their daughter before work, she said. The couple’s babysitter, Brielle Blemle, said she saw Martinez parked on the main road outside the apartment complex more than once. Loiselle bought blinds. Another time, Blemle said, a state trooper’s vehicle briefly followed her as she left Loiselle’s place. “There was literally nothing we could do,” she said. “And Sarah did try.” Loiselle and the nurse made complaints with Martinez's station. Loiselle said she also left several messages there but got no response. (Her lawyer, however, received a letter from Martinez’s attorney instructing Loiselle and her “friend” to stop making allegations of stalking or harassment to the state police.) Then, in May, Loiselle was shopping in Walmart when Martinez suddenly showed up in the baby food aisle. He insisted it was a coincidence, but after a tense exchange Loiselle called the police, to establish some kind of official record. This time, she contacted a large dispatch center instead of Martinez’s station. But the Walmart encounter didn’t give police much to go on, and after interviewing Martinez, they took no further action.

An abusive officer, said David Thomas, a police consultant, is “a master manipulator with a Ph.D.”

The couple briefly reconciled later in the summer, but Martinez’s controlling behavior surfaced again, Loiselle said. One of her few close friends in the area, Cortney Lewis, recalled that Loiselle was uncharacteristically timid around him. Lewis, a no-nonsense hairdresser in her early twenties, also got the impression Martinez only wanted Loiselle to be friends with the wives of his own close buddies. Then, in early 2014, some months after Loiselle and Martinez had finally split up for good, Lewis heard that Loiselle had been asking a lot of personal questions about her. She wanted to know, for instance, whether Lewis or one of her relatives had ever been in trouble with the police. Furious, Lewis confronted her friend, and Loiselle explained that Martinez had raised some concerns about her family. Lewis wondered: Had Martinez been looking up private information about her in police databases? She decided to report her suspicions, even though Loiselle begged her not to “poke the bear.” “He’s not the fucking president,” Lewis said.

-

05/19/13:

Cortney Lewis

Cortney's relative -

05/23/13:

Cortney Lewis

Cortney's relative - 05/23/13: Sarah Loiselle

On January 15, 2014 Loiselle was at home when there was an unexpected knock on her door. The man standing outside introduced himself as Sergeant Jeffrey Whitmarsh. He was wearing dress clothes, not a uniform, and Loiselle started shaking. She brought Whitmarsh into her living room, where her daughter’s toys were scattered all over the floor and just stared at him, afraid that he was there to somehow protect Martinez or his department.

Whitmarsh tried to put her at ease. “I can’t put myself in your shoes Sarah, I just can’t,” he told her, according to a transcript of the conversation. He explained that he had been investigating Lewis’s complaint. He also made a point of saying that he worked about an hour and a half away, so he didn’t know law enforcement people in this part of the state. Whitmarsh opened a binder and showed Loiselle some printouts, which he said were only a snapshot of searches Martinez had run in DELJIS, the Delaware police database that houses close to 12 million records, including addresses, car tags, driver’s licenses, fingerprints, arrest history, protective orders, police reports, even nicknames. Loiselle had trouble focusing. She had suspected that Martinez might be using his police authority to keep track of her, but never anything like this. As she tried to keep it together, Whitmarsh said, “The concern I have [is]: How far he is going to learn as much as he can about you?”

Ultimately, Loiselle would learn that Martinez had looked up vehicle registrations on cars parked inside her apartment complex on fifteen dates and had run searches on the owners, according to the Delaware State Police. Police also said that between July 2012 and December 2013, Martinez had run or attempted dozens of searches—on Loiselle, her friends, colleagues, casual acquaintances, ex-boyfriend, Facebook friends, a day care provider and the nurse at the hospital, among others. And he had searched for information on his new girlfriend, too. When exchanging Jasmine, Loiselle had sometimes caught glimpses of her—a woman with blonde hair in a banana clip, hidden behind the tinted windows of Martinez’s car.

In 2011, Karen Tingle was working as an emergency medical technician not far from Lewes. She had been a 911 dispatcher for years before realizing that she wanted to be the person responding to the distress call, not the person picking up the phone. She adored her job, but she was also a bit lonely. At 34, she had two children and three ex-husbands—the result, she thought, of an overly trusting nature. “I always look for the best in people,” she said. “You can tell me something and I will believe you until I have a good reason to know otherwise.”

That October, not long after Loiselle had first moved in with Martinez, Tingle had profiles on Match and PlentyOfFish. In pictures, she looked toned and tan, with a slender face framed by thick blonde hair. When she got a message from a guy called Andrel Martinez, she recognized him—he was a state trooper she knew of through work. He was also Tingle’s type: a strong personality with a protective side. On their first date, he seemed gentle and funny. When Martinez started dropping by the ambulance station with a cup of coffee or a Butterfinger bar, Tingle was flattered. Her best friend and fellow EMT, Jackie Marshall, recalls him showing up “pretty much every shift.”

“I always look for the best in people,” Karen Tingle said.

MELISSA JELTSEN

“I always look for the best in people,” Karen Tingle said.

MELISSA JELTSEN

They dated casually for almost a year, Tingle said, although they sometimes went for extended periods without seeing each other. Tingle attributed this to the demands of Martinez’s job, but whenever she pressed for more commitment, he told her he wasn’t ready, she said. Then one day in the summer of 2012, Tingle was killing time between calls when a colleague said she’d heard Martinez had gotten a woman pregnant. Apparently, they were having a baby shower the very next day. The co-worker, who asked not to be named, said Tingle was visibly stunned. Tingle later learned that the rumor was true and that the woman’s name was Sarah Loiselle.

Martinez didn’t deny the pregnancy, Tingle recalled, but told her that it happened after a one-night stand and that he hardly even knew Loiselle. Tingle stopped seeing him, but said they started dating again about six months after the baby was born. Almost immediately, Tingle got pregnant.

- 03/08/13: Karen Tingle

They were separated for most of Tingle’s pregnancy. During this period, she was crushed to learn that Loiselle hadn’t been a random hookup at all. She and Martinez had dated seriously, even lived together—and now they seemed to be seeing each other again. And yet after Martinez and Loiselle broke up for the last time, Tingle decided to forgive him. She didn’t want to raise another child alone and she thought Martinez would be a good father. She started living in the house he’d once shared with Loiselle in the winter of 2013. Days before Christmas, Tingle gave birth to a girl we’ll call Kate, with Martinez by her side.

- 10/15/13: Sarah Loiselle

- 10/28/13: Loiselle’s friend

But Loiselle remained a constant presence in their lives. Tingle recalled Martinez telling her that his ex-girlfriend was a “vindictive female” who was making up vicious lies in order to take his child. She was moved by how relentlessly he was fighting for Jasmine—Loiselle must be a real piece of work, she thought. Her mother, Janice Arney, was outraged, too. “He led us to believe that Sarah was a horrible mother, and he was trying, through the court system, to get [Jasmine] away from her,” Arney said. Once, Tingle recalled, Martinez had gone into a Walmart while she stayed in the car. After he came out, Tingle said, they were still in the parking lot when Martinez got a tip-off on his phone from a police dispatcher: Loiselle had just called the cops on him. (Loiselle said she heard about this from Martinez himself, who bragged to her that he had “friends who look out for him.” The dispatcher and the Delaware State Police declined to comment.)

- 11/07/13: Karen Tingle

- 11/12/13: Sarah Loiselle

- 11/20/13: Loiselle’s boyfriend

- 11/21/13: Loiselle’s boyfriend

- 11/25/13: Loiselle’s boyfriend

- 11/25/13: Sarah Loiselle

One day in January 2014, two state police officers showed up at the house to tell Martinez he was being suspended with pay and had to turn over his gun and badge immediately. Tingle couldn’t understand what was happening, although she suspected it must have something to do with Loiselle. Still, she did her best to keep things normal. Martinez, an enthusiastic cook, whipped up steaks or Cuban sandwiches for family dinners. But in March, the couple were driving to pick up Tingle’s oldest daughter, who we'll call Kristen, when a police minivan loomed behind them, lights flashing. In Tingle’s recollection, Martinez pulled over to let the van pass but it stayed on him. He stopped the car, got out and learned that he was being arrested. By the time Tingle got home, it was full of police searching for evidence.

Martinez was charged with harassment and felony stalking, as well as 60 counts stemming from his DELJIS searches of Loiselle and others, according to a criminal complaint. Still, Tingle stood by Martinez: As far as she was concerned, Loiselle was crazy. Four days later, Martinez was placed on suspension without pay and benefits. He was at home all the time. That was when, Tingle said, his temper got worse.

A few months after his arrest, he cornered Tingle against a wall and punched through it next to her head, she said. It was the first time he’d done anything like that, and when he promised it would never happen again, she believed him. She didn’t feel like she could abandon him when he was under such terrible stress—and she badly wanted Kate to have a father. That spring, they moved out of Martinez’s place and into her home on the corner of her parents’ farm to save money. Her mother bought a tricycle for the kids; the family sometimes roasted weenies at a firepit by a small pond. In June 2014, at a clerk of the peace, Tingle and Martinez got married.

On a dreary Friday earlier this year, Mark Wynn was pacing in front of a group of police officers and prosecutors in a hotel ballroom in Portland, Oregon. He’d warmed up the audience with a few well-worn jokes in his mellow drawl, and now he was getting to the tricky part. “This can be kinda weird. Stay with me now,” he said. “This, in my mind, is who people of policing are.” He reeled off a list of characteristics that officers are encouraged to master—to control their emotions, to interrogate when suspicious, to match aggression when challenged, to dominate when threatened. These hard-won habits were “a good thing,” he reassured the group. But they could also “super-charge” abusive officers. “You got an offender in the ranks—man, you got a mess on your hands,” he concluded. “Because they now are using what you gave them to be a better abuser, no question about it.”

Police officers can find their instincts hard to turn off when they leave the station—a phenomenon known as “authoritarian spillover.” Seth Stoughton, an assistant professor of law at the University of South Carolina, still finds himself slipping into “cop mode,” although he hasn’t been a police officer in more than a decade. When he was still on the force, Stoughton once became convinced his wife was lying about a big scratch on their car. “Let me be clear, I interrogated her using a number of the techniques I had learned as a cop,” he said. “It was not a good scene.” It also turned out that he was wrong, and to this day, the memory makes him uneasy. (His wife, Alisa, said she “felt very attacked and uncomfortable. I had never seen that side of Seth before.”)

Because police are trained to use a continuum of force that starts with non-physical tactics and ends with lethal violence, behavior that seems routine to them can be terrifying for family members. Punching or grappling, for instance, might only rank a 5 or a 6 on the use-of-force scale, wrote Ellen Kirschman in a book for law enforcement families called I Love A Cop. But for family, yelling might feel like a four and pushing could be a 7. One study of more than 1,000 Baltimore police officers found that officers with stronger authoritarian attitudes—such as a need for “unquestioning obedience”—were more likely to be violent toward a partner.

Since the late 1990s, Mark Wynn has focused on exposing the problem of abusive police officers.

Courtesy of Mark Wynn

Since the late 1990s, Mark Wynn has focused on exposing the problem of abusive police officers.

Courtesy of Mark Wynn

Wynn is careful to emphasize that police work doesn’t turn people into abusers. He has come to believe that the most dangerous offenders are those who enter the force with abusive tendencies, which are intensified by the job and the power that comes with it. Officers learn “command presence”—how to control a situation by physically and verbally projecting strength. They are taught to dominate suspects with precise techniques like digging into a pressure point or locking a wrist. They possess access to databases and other resources that can be used to facilitate abuse—license plate data, for instance, could be used to closely monitor a person’s travel patterns. They may even be capable of locating a person if she changes her name or social security number. An abusive police officer, said David Thomas, the IACP consultant, is “a master manipulator with a Ph.D.”

“So the question is, ‘Do we break the code?’” Wynn asked his audience. Over the years, he’d come across numerous cases of officers protecting their own—arriving at court in uniform to intimidate a victim, driving by the house of a colleague’s wife to report on her movements. But the urge to shelter a fellow officer, he cautioned, isn’t necessarily sinister. He recalled once assigning a detective to investigate abuse allegations against a colleague. The detective looked at the file and blanched: The officer in question had saved his life, twice. Wynn knew what that meant. He put another detective on the case.

One potential solution is to establish a mandatory procedure to be followed when an officer is accused of abuse, covering everyone from the responding officer to the chief. “You cannot treat this case like any other case,” said Wynn, who has been lobbying police chiefs since 1999 to adopt a policy developed by the IACP. And yet most departments don’t have such a protocol. (The Delaware State Police wouldn’t comment on whether it has one.) Ultimately, Wynn believes that the most effective solution of all is to screen prospective police officers for any history of domestic violence or sexual misconduct. He also advises departments to check whether they have protective orders anywhere they’ve lived or worked. Still, many of the chiefs Wynn talks to remain skeptical of his proposals, he said: “They say, ‘Oh, that doesn’t happen here. We’ve never had that problem.’”

The first time Tingle tried to get help was on September 9, 2014. Driving home from a dinner date, the couple had started arguing in the car. Their accounts of what happened next diverge radically. According to Martinez, Tingle hit herself and threatened to report him to the police. But in Tingle’s telling, Martinez grabbed her hair and struck her face into the dashboard and then the passenger window, causing a sharp stab of pain. She asked him to let her out, at first calmly and then frantically. He refused and started recording her on his phone, locking the doors. She screamed and banged on the window, waving at other cars for help. About the only thing they agree on is that he recorded her.

A driver of a nearby white Ford truck noticed the commotion inside the car. He told HuffPost he watched in shock as a woman climbed out of the window at a stoplight. Tingle ran over and asked him if he could take her to the closest police station, he said—“in distress, like, in a panic.” He recalled that her face looked swollen and bruised and that she said her husband had hit her. He drove her to the Seaford Police Department. When they arrived, he said, Martinez was already there.

Tingle ran into the station with her husband right behind her. Before she could do anything, she said, Martinez identified himself as a state trooper. According to the brief description in a domestic incident report, Tingle said Martinez had struck her head on the dashboard—behavior categorized as “offensive touching.” Martinez was allowed to leave.

One of the photographs taken by Tingle's friend, Jackie Marshall.

COURTESY OF KAREN TINGLE

One of the photographs taken by Tingle's friend, Jackie Marshall.

COURTESY OF KAREN TINGLE

After the police brought Tingle home, her friend Jackie Marshall, who’d been babysitting, took a few photos. In one, a large bruise is visible on the side of Tingle’s face. “I told her that day that she was going to end up dead if she didn’t do something about it,” Marshall said.

Martinez was never arrested or charged. When asked why, a spokesperson for the Seaford Police Department said the case was referred to the state attorney general’s office, which has to approve or cooperate with the arrest of a police officer. However, Carl Kanefsky, a spokesperson for the Delaware Department of Justice, said there was no such requirement and that it was the Seaford Police Department which determined that criminal charges couldn’t be sustained.

About a week after the incident in the car, there was also a major development in Martinez's case with Loiselle. In a plea deal, prosecutors dropped dozens of charges, including the one for felony stalking. In exchange, Martinez pleaded guilty to two counts of illegally obtaining criminal history. “It was the judgment of experienced prosecutors, including those who prosecute domestic violence cases, that there wasn’t enough evidence to proceed on all of those counts,” said Kanefsky.

By this point, Tingle wanted to leave Martinez. She just didn’t know how. Most of all, she worried that if she broke up with him, he would take Kate away from her. So she simply tried to stay out of his way. On November 6, the couple got into a fight in Tingle’s bedroom. Tingle said she picked up 10-month-old Kate and was walking away when Martinez grabbed a heavy lamp off the bedside table, pulling his arm back as though he was going to hit her. Instead, she said, he dropped the lamp and grabbed her by the throat. While she was still clutching Kate, he pushed her into the bathroom by the neck.

Tingle couldn’t breathe, she said: “I thought I was getting ready to die, and so was [Kate].” She recalled the bathroom sink digging into her back and the sound of Kate screaming while she tried not to drop her. Martinez’s face was right up in hers and she wet herself. “I have never seen a look in someone’s eyes that evil before in my life, and I hope I never see it again,” she said.

Somehow, she said, she managed to knee Martinez and make it back into their room. When Martinez shut himself inside the bathroom, she said, Tingle hastily placed Kate in the carrier and ran for the car. She had only driven five minutes down the road when Martinez called. ‘You forgot something,’” she recalled him saying and then it hit her: Fourteen year-old Kristen was still in the house.

So she went back. When she walked in the door, Martinez took her phone, keys and wallet, she said, and told her she wasn’t going anywhere. She didn’t attempt to call the police. Martinez had told her once that if they tried to arrest him again, he wasn’t going, Tingle said, and she was afraid of what he meant by that. So she put Kate to sleep and told Kristen to stay in her room and keep the door closed. Then she got into bed next to Martinez.

The following day, Martinez had to leave the house to pick up Jasmine and Tingle acted as though she was going to work as usual, putting on her uniform and doing her hair. As soon as he drove away, she collected Kristen from school and went to the state police in Bridgeville. On the way, she texted Martinez and told him the relationship was over. He replied:

At the station, she told a detective what had happened. The probable cause affidavit notes that red marks were visible on her neck. As photos were taken for evidence, she was flooded with relief. She arrived home that evening just as Martinez was being led away by police—he had come to the house, despite her texts, to cook hot dogs with Jasmine. Martinez was charged with strangulation, second-degree unlawful imprisonment, menacing, endangering the welfare of a child and malicious interference with emergency communications. The police left Jasmine with Tingle. And that was how Tingle and Loiselle met late that night—when Tingle brought Loiselle her sleepy daughter. By then, Tingle’s head was aching and she was too exhausted to really talk.

But the two women spoke in the coming days. Loiselle would only call Tingle from a restricted number at first, because she was worried that Tingle might go back to Martinez. Slowly, though, they peeled back the layers of their stories. Tingle dug up her online dating emails from Martinez going back to 2011, when Loiselle had just moved in with him, and they discovered the extent of his deception. Loiselle had known for a while that Martinez had a new wife and another baby—but she had no idea that he’d been entangled with Tingle for nearly the whole time she’d known him. Tingle, for her part, was taken aback to find Loiselle so friendly and big-hearted—nothing like the unhinged woman Martinez had described. For the first time, both women realized, they had found someone who believed their story, every word.

Andrel Martinez discussed his case for around half an hour on the phone earlier this year. He didn’t seem remotely defensive or guarded; in fact, he could be funny, even charming. Occasionally, he punctuated his narrative with a rueful chuckle, as if to say: Can you believe this? His story, he observed, had become like “something out of a Tom Clancy novel.”

He’d lost his job in March 2015, after his DELJIS credentials were revoked. That June, he also accepted a plea deal in the strangulation case. In 45 states, including Delaware, strangulation is classified as a felony. It is one of the most reliable predictors of a future homicide in domestic violence cases—but it is also notoriously hard to prosecute and often reduced to a lower charge in a plea bargain. Martinez pleaded no contest to assault in the third degree, a violent misdemeanor. The judge suspended the one-year prison sentence for a year of probation on the condition that Martinez had no contact with Tingle or her children.

On the phone, Martinez had a ready explanation for just about everything. Loiselle, he explained, was a “controlling” girlfriend. She had started making allegations because he had sought equal custody of Jasmine, he said, describing one of the protective orders she’d sought as “frivolous” and “false.” As for Tingle, Martinez said she’d invented accusations of violence. “She hit herself and then said, ‘I’m going to tell the police you did it,’” he said, letting out a high-pitched laugh.” He referenced cellphone recordings of Tingle that he said supported his version of events but had been withheld by the state in legal proceedings. (His previous attorney has also said in court that Martinez has “multiple recordings” of Loiselle that disprove her stalking claims.) On several points, Martinez’s accusations mirrored those of both women. In a written document from one proceeding, Martinez accused Loiselle of berating him, threatening him, forcibly taking their daughter from him, driving by his residence and questioning his friends. He, too, expressed disappointment in the authorities’ response. “I was a good cop,” he said. “[I] tried to understand both sides of the story before I acted, and I felt like that was never given to me.”

Martinez after his arrest. DSP

Martinez after his arrest. DSP

Over and over, Martinez emphasized his devotion as a dad. In court documents, he admits to using DELJIS “in an effort to check into the safety and welfare of [my] daughter.” He elaborated on his thinking on the phone. “I’m going through a custody dispute where I was threatened. The cop instinct came out in me to be vigilant upon myself, to be vigilant upon my kids,” he explained. “[But] I never used anything from [DELJIS] other than peace of mind and perhaps knowing, ‘Hey, I can put that face with a name now if I’m approached in public.’” The whole experience had taught him a huge lesson, he said: He had picked the wrong women. “You don't let the devil into your house that easily,” he said. Near the end of the call, he stated, “I don't feel I was the aggressor in any sense of the entire situation.” (Some time afterward, he tried to take our conversation off the record.)

We went to extensive lengths to investigate Martinez’s claims. Martinez wouldn’t share the recordings he mentioned. Kanefsky, the Delaware justice department spokesman, said prosecutors “were not provided nor did they ever hear any such recording.” The state police declined to comment on extensive questions and are not required to release internal investigative files. Martinez said he couldn’t provide more information because he is still involved in legal proceedings: In a suit against the state police, he claims he was subjected to harsher punishment because he is Hispanic, alleging that people involved in the DELJIS investigation and others had made racist comments. (The Delaware State Police rejected these claims in a court filing.) His attorney responded to a detailed list of questions by saying simply: “Mr. Martinez disputes the accuracy of all statements made by your sources.”

We also contacted Martinez’s family and a number of his friends. Gordon Smith is a local father’s rights activist who made headlines several years ago after his ex-wife was arrested for fabricating domestic violence allegations (she eventually pleaded guilty to falsely reporting an incident.) He recalled that Martinez had reached out to him around the time of his first arrest. Smith was sympathetic: Domestic violence was real, he explained, but it had become a “cottage industry” in Delaware, where it could be used to “get an upper hand in a divorce custody battle.” Smith admitted he was “definitely surprised” when he learned that more than one woman had accused Martinez of abuse. Still, he felt his friend was treated unfairly at the DELJIS hearing, which he attended. “Having the two individuals [Loiselle and Tingle] sitting there, in my opinion, prejudiced the whole thing,” Smith said. (Martinez’s mother spoke in his defense at the hearing but declined to comment for this story.)

“What about some police courtesy?” Martinez asked. “Aren’t I still a police officer?”

Loiselle and Tingle’s stories have remained consistent—in months of interviews with us, in pages of court documents, in police reports when the incidents occurred. We also discovered additional instances where Martinez’s behavior was called into question. In July 2015, his parole officer observed that Martinez was “covertly recording” a home visit. The next week, he was caught attempting to smuggle an Olympus digital voice recorder into the probation office in his waistband. (It was recording at the time, according to a court document.) Another incident occurred at the visitation center where Loiselle and Martinez were supposed to exchange their daughter, using separate entrances and under staff supervision. Martinez was about to return Jasmine to Loiselle when he said he was going to take her to the emergency room instead because she had a diaper rash. The trooper who had escorted Loiselle to the center had known Martinez for more than 10 years. He advised him he would be arrested for violating a court order if he left with Jasmine. “What about some police courtesy?” Martinez asked him, according to the trooper’s report. “Aren’t I still a police officer?” The trooper reminded him he’d been suspended.

Both women were disappointed with the outcome of the various cases, but prosecutors did appear to pursue the charges against Martinez aggressively. DELJIS, too, moved quickly after Lewis reported her concerns. Peggy Bell, the organization’s executive director, declined to comment on specifics, but emphasized it was rare for officers to lose database access: Only one or two a year have their credentials permanently revoked. (Bell herself said she won’t even look up an address to send an officer a bereavement card.)

We also spoke to one officer who was familiar with Martinez’s case. He was not authorized to talk on the record, so he met for lunch, arriving in uniform at a restaurant. He said he had become “very concerned why this guy wasn’t being dealt with a little more forcefully by the state police.” It seemed to him that Martinez was “manipulating the system” and that the police “doubted the victims and made him a victim.”

The officer was clearly troubled—not just by this case but by its implications. Law enforcement needed to be more aware of the effects of emotional abuse, not just physical harm, he observed. He talked about how police possess a unique authority and trust that could be wielded against a victim in destructive ways. “They call domestic violence [and] rape a crime of power,” he said. But “the ultimate power” was the ability to arrest someone. “And the way the state police are viewed in this state?” he added. “We’re viewed very well.”

After he left, the waitress remarked that at the restaurant, they loved their police officers.

Earlier this year, Karen Tingle was living in an isolated village on a mountain, a long way from her former home. After Martinez accepted the plea deal in the summer of 2015, Tingle kept noticing strange things. She found tracks through the corn field next to her home. She was followed by a vehicle she didn’t recognize. After writing a panicked email to her state representative, Tingle was granted a meeting with the Delaware attorney general, Matt Denn, who ordered Martinez to be fitted with an ankle bracelet as an additional condition of his probation and approved funding for a security system in Tingle’s home.

But the strange things didn’t stop. In September of that year, Tingle showed up at the Bridgeville police barracks. Her “face was red, eyes watery and blood shot [sic] and she had tears coming from her eyes,” Corporal M. Sammons wrote in an affidavit. He described watching Tingle hand another officer “a red card with a message to a wife from Hallmark. Inside the card it was signed 'CUNT' and also had a picture of a child with a message written on it: 'DEAD MISTAKE.'” The child in the photo was Kate.

Sammons requested the GPS data from Martinez’s ankle bracelet, which showed he hadn’t been to Tingle’s house. This, Sammons wrote, “does not prove he did not have someone deliver [the card] on his behalf.” A few months later, a grand jury indicted Martinez for felony stalking. The charge, which requires proof of at least three incidents, was eventually dropped: Kanefsky, the Delaware justice department spokesman, cited the evidence that Martinez “was not in locations requisite to prove the stalking charge.” He also noted that “the evidence was not necessarily at odds with the victim’s version of events.” To Martinez, this episode was just another example of how the system had failed him. “I went 14 months with a GPS on my leg facing felony charges, and it seemed like she was just going every month to the police station,” he said. “All kinds of shit...and then the state dismissed the case. Crazy.” As for Tingle, the state relocated her in late 2016 under a confidential program it uses in limited cases for witnesses or victims who need protection.

Tingle left her home in Delaware after a number of unsettling incidents.

MELISSA JELTSEN

Tingle left her home in Delaware after a number of unsettling incidents.

MELISSA JELTSEN

When we visited her, a thick blanket of snow covered the ground and the roads were slippery with black ice. We talked in the spacious living room of her furnished house. It was awkward sitting on other people’s furniture, Tingle remarked from a voluminous blue sectional. Her boyfriend, whom we’ll call Ryan, brought her a grilled ham and cheese sandwich. Tingle and Ryan started dating in 2015, some months after she had split with Martinez. Tingle found him kind and strikingly non-judgmental. He’d quickly adopted the role of protector—triple checking that doors were locked, monitoring the vehicles parked outside—and when Tingle moved, he came with her. As we talked, Tingle shifted uneasily on the couch: She was heavily pregnant and it was hard to get comfortable. Kate, now 3, bounced around the living room, giddy to have a guest. They didn’t have many visitors, Tingle explained, because they were trying to keep their location secret. She wouldn’t register her car or most of her bills to her new address. All it would take, Ryan explained, was a court filing accidentally made public, a tag on a social media post, and Martinez could find them.

Tingle has moved again since our visit. She looks after her baby. She waits tables, which seems a long way from the EMT career that once gave her such pride. “I never understood why women stayed after I took them to the hospital beaten to a pulp,” she wrote in a text message. “Now I understand. All those women I thought were stupid, now it’s me.” When she talks about that terrifying final night with Martinez, her voice, already deceptively girlish, is barely audible.

One of her few comforts is her friendship with Sarah Loiselle, who had been placed temporarily in the confidential protection program in 2014 and relocated. She, too, has since moved again. Loiselle doesn’t really like to talk about the precautions she takes to keep her location secret, although she has enrolled Jasmine in a federal program that would alert her if Martinez ever tried to get their daughter a passport.

Sarah Loiselle and Karen Tingle.

COURTESY OF KAREN TINGLE

Sarah Loiselle and Karen Tingle.

COURTESY OF KAREN TINGLE

Their friendship is an unlikely one. Tingle is one year older, but she views Loiselle as a kind of big sister. To her, Loiselle is elegant and well-dressed while she was raised on a farm and looks it. Loiselle admits that she is more direct and outspoken. “I’m not that type of person,” Tingle said, adding quietly: “Maybe I don’t stand up for myself.” She solicits Loiselle’s advice on everything—how much baby aspirin to give a teething child, how to deal with lawyers. (After we started reporting this story, Martinez moved to seek joint custody of both Jasmine and Kate.)

For the past two years, Tingle, Loiselle and their daughters have all met up to celebrate Jasmine’s birthday. On one visit, after a full day of celebration and cake, the women sat outside as the night closed in and Tingle felt safe and happy. She considered moving somewhere near Loiselle so their improbable family could be together more often. Loiselle argued against it. She wanted Tingle and her daughters to be closer, too. But she thought it was far too risky for all of them to live in the same place, just like “sitting ducks.” And so the women went back to their new lives and kept on trading little jokes and updates on their jobs and kids and ups and downs—pretty much anything but Martinez. On a recent day, Tingle opened a Snapchat message from Loiselle. “Wish you were here,” it read, over a photo of an empty beach.

This story was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.